“Infinite past makes present tense.”

— from “The Campaign to Confer the Public Service Star on JBJ” (2007) by Eleanor Wong

Serene Chen is cradling a ukulele in her arms. Her warm alto fills the black box, husky and honeyed against the nylon twang of her instrument, and against grainy projections of scanned photographs from the 1990s where a younger Chen, grinning and gleaming, stands shoulder to shoulder with other cast members from Dick Lee’s 1994 musical “Kampong Amber”. Chen is singing the musical’s theme song, “Bunga Sayang”, the kind of achy and delicate ballad whose soaring chorus might be an offering to a lover, an ode to a disappeared kampung Singapore—or in tender remembrance of a friend now gone.

In Chen’s case, this is the late Emma Yong, the beloved actress who could be both luminous ingénue and lacerating comic relief, and who died of stomach cancer just over a decade ago. But the song is laced with all sorts of other nostalgias. As the notes cascade over us, I remember interviewing choked-up theatre practitioners in the wake of Yong’s death as a young reporter mapping out the nodes and branches of personal relationships in Singapore’s theatre industry. And I also remember Rahimah Rahim’s rendition of the same song in Royston Tan’s nostalgia-soaked short film of the same name, her warm vibrato mingling with Chen’s own. Memories sediment on top of each other in “The Vault: Past Perfect”, and each excavation reveals a different cross-section of emotional detritus and stratas—depending on your own relationship with Singaporean theatre and its histories.

If we think of grammar as a linguistic structure within which we might make shared meaning of a world, or fumble towards collective points of reference, then “Past Perfect” is the attempt of a specific generation of Singaporean theatremakers to talk about what they “had made” in the past. Implicit in these tensorial tensions are questions about the theatremakers of the present (“are making”) and the future (“will be making”), and how they might inherit and reshape these structures.

What is the grammar of our relationships with each other?

The structure of the show is straightforward. Performers Chen, Nelson Chia, and Oniatta Effendi each take turns to offer a monologue about their experience coming of age as a theatre practitioner in the 1990s. The performers each embody different kinds of training processes and lineages, a select reflection of the multilinguality of the Singaporean theatre experience, and how theatremakers and performers who entered the industry in the 1980s and 1990s were often filtered into various language streams, whether by choice or circumstance.

They talk about muddling their way through early auditions and the painstaking preparatory processes they endured before each became proficient in their theatrical genres. Chen spends hours in a university library translating a Traditional Chinese playscript, word by word, into the Simplified Chinese she can understand. Chia is made to sweep stages and boil eggs for an audience; as a student, Oniatta wanders the Geylang red light district for character research.

The trio have since become respected artists: Chia is now artistic director of the Chinese-language theatre company Nine Years Theatre, known for its physical and vocal precision; Chen is an award-winning actress, radio host, voice artist and lecturer; Oniatta invested decades in arts education, and her creative practice now centres the sculptural possibilities of batik on the body’s silhouette (she’s the founder of her own clothing line, Baju by Oniatta).

Yet as they peer back, it’s clear that in many ways, they and other artists who contributed to the early legitimisation and professionalisation of the Singaporean theatre industry in the 1980s and 1990s were creating the grammatical foundations we know today: its subjects, objects, articles, particles, tenses, tensions. Fluent speakers of a language rarely pay attention to grammar. We take for granted these shared rules—until, of course, they are broken.

We can see the team, including director Casey Lim and dramaturg-writer Robin Loon, doing their best to steer away from the comparisons that often surface between generations of artists (“in my day...”), but these emerge inadvertently in other ways. From their collective recollections, we get a sense of the variety of training processes and lineages that have emerged from Singaporean theatre, but also how canonisation (or even deification) occurs from the slow accrual of relationships with both people and place. Kuo Pao Kun, William Teo, the Substation, the Fort Canning Drama Centre: the performers all describe the gravitational pull exerted by the late theatre pioneers who shaped their artistic identities and ethos, as well as beloved rehearsal and performance sites now demolished or defunct. These names transform posthumously into the industry’s shared temporal reference points, but also as a kind of carbon-dating of a practitioner’s entry into the scene: who worked with Kuo, who received his sagely aphorisms, who performed at the old Drama Centre, who responded to audition notices in the former “Section Two” of The Straits Times (ST). It was later renamed “Life”.

There’s a sense of DIY underscoring the performance, evoking the analogue approaches of the time. All the performers read from scripts on stands in front of twin slideshow projections, and there’s a deliberate austerity to the mise en scène with its black folding chairs and the monochromatic colour palette of the cast’s costumes.

It’s an aesthetic reminiscent of the work that Lim and Loon have done before. Both are co-founders of Centre 42, a non-profit dedicated to the documentation and development of Singaporean theatre, and their professional remit often melds with their personal convictions when it comes to archiving performance. The liveness of performance often resists the conventional strategies of the archive; a single video recording or transcript (or even this review) are often valiant failures of documentation, capturing a single night, a certain mood, a particular permutation of audience members who may react to any number of decisions the performers may choose to take. Because of this, Centre 42 has often relied on a variety of approaches to make sense of the stories that Singapore theatre may hold, and the staff and its resident artists regularly wade through an enormous accumulation of programme booklets, interviews, reviews, recordings, photographs and other memorabilia that form an ever-expanding assemblage of what Singapore theatre might have been and is still becoming. Likewise, Lim and Loon have chosen to archive performance through performance itself, giving a physical shape to oral histories that can at least demonstrate what is accrued within the bodies that populate a stage—and also what happens to these bodies and memories over time.

“Past Perfect” is part of the centre’s “The Vault” residency, one that initially seems to hold two goals in curious and opposing tension: to “safe-keep” theatrical works, but also reinvent them through “contemporary responses” that do not “merely document the past”. Can you keep something safe if you can’t keep it from changing? A first iteration of “Past Perfect” was staged at the Singapore International Festival of the Arts in May 2023, part of a platform subtitled “there is no future in nostalgia”. The tagline was drawn from an Arthur Yap poem bemoaning the obliterating forces of urban renewal in the city-state. Renewal is always already at work; this restaging is itself a process of both renewal and revision. If there is no future in nostalgia, then why do we always return?

Singapore theatre indulges, fairly often, in theatre about itself. This includes Lim and Loon’s previous forays into the genre of documentary and oral history, such as “Casting Back” (2012), also anchored by the curated oral histories of two veteran performers, Nora Samosir and the late Christina Sergeant. The two-hander, which pre-dates the founding of Centre 42 by two years, now feels like a sketch for what “The Vault” would eventually become. Both actors revisit their favourite characters, relish their “glorious failures”, and return to the rehearsal rooms of theatre venues now defunct and demolished. The safe-keeping that theatre offers is a safety from the flattening forces of a state and a mainstream media that often present themselves as the authoritative chroniclers of a Singaporean experience.

Nostalgia, in state hands, becomes a form of temporal dysmorphia: we look in the mirror and see things that aren’t really there. We look into the past to see things sanded off, over-polished, shiny and clean. We look again to find that the moral panic around controversial art has eclipsed the art itself. Singapore’s state-adjacent media is regularly complicit in the sensationalising of what art critic Jennifer Doyle prefers to call “difficult”, rather than “controversial”, performance work. Calling attention to difficulty, Doyle believes, can defuse and diffuse the reactive outrage surrounding certain kinds of art, and reframe one’s engagement with artwork as a commitment to struggling with and sitting with the complexity of our world. “Past Perfect” does this with a clear-eyed offhandedness, allowing performer Oniatta Effendi to reflect candidly on the aftermath of “Anak Melayu”, Noor Effendy Ibrahim’s confrontational play about disaffected Malay youth first presented in 1992. Oniatta describes the severity of the critique the play received from the nation’s Malay-language broadsheet, as well as her mother’s paranoia that the Internal Security Department might be trailing her.

Embodiment and reenactment are strategies that performers and performance-makers frequently rely on in Singapore to wrest back some sense of agency in the (re)telling of their histories, and the temporal distortions that a manufactured “nostalgia” can bring. When it comes to theatre about theatre, playwright-director Chong Tze Chien combed through decades of reports and reviews for “Rant & Rave” (2012), where he compresses 30 years of Singapore theatre’s relationships with the mainstream media into just over an hour. Reporters and critics from ST, TODAY, The Business Times and other print publications are drawn into an imagined dialogue and debate with artists and with each other, animated by performers Siti Khalijah Zainal, Janice Koh (2012 staging) and Karen Tan (2014 staging). What emerges—as with “Casting Back” and “Past Perfect”—is a new constellation of personas whose paths may otherwise not have crossed.

During “Past Perfect’s” post-show dialogue, I asked Chia, Chen and Oniatta if they had worked together before this show; they hadn’t. Lim and Loon had assembled performers and practitioners whose trajectories run parallel to each other, creating a new historical event in the process of an archival intervention: the return remakes the memory, dog-ears it, creases it, adds new textures, fades it with exposure to the light. I can feel Chia returning to a taxi ride with Kuo Pao Kun, and Oniatta returning to the moment she takes off her hijab for a show. When we narrativise a lineage, are we making sense of what happened, or are we bending reality to our will? The answer is always both, or somewhere in-between.

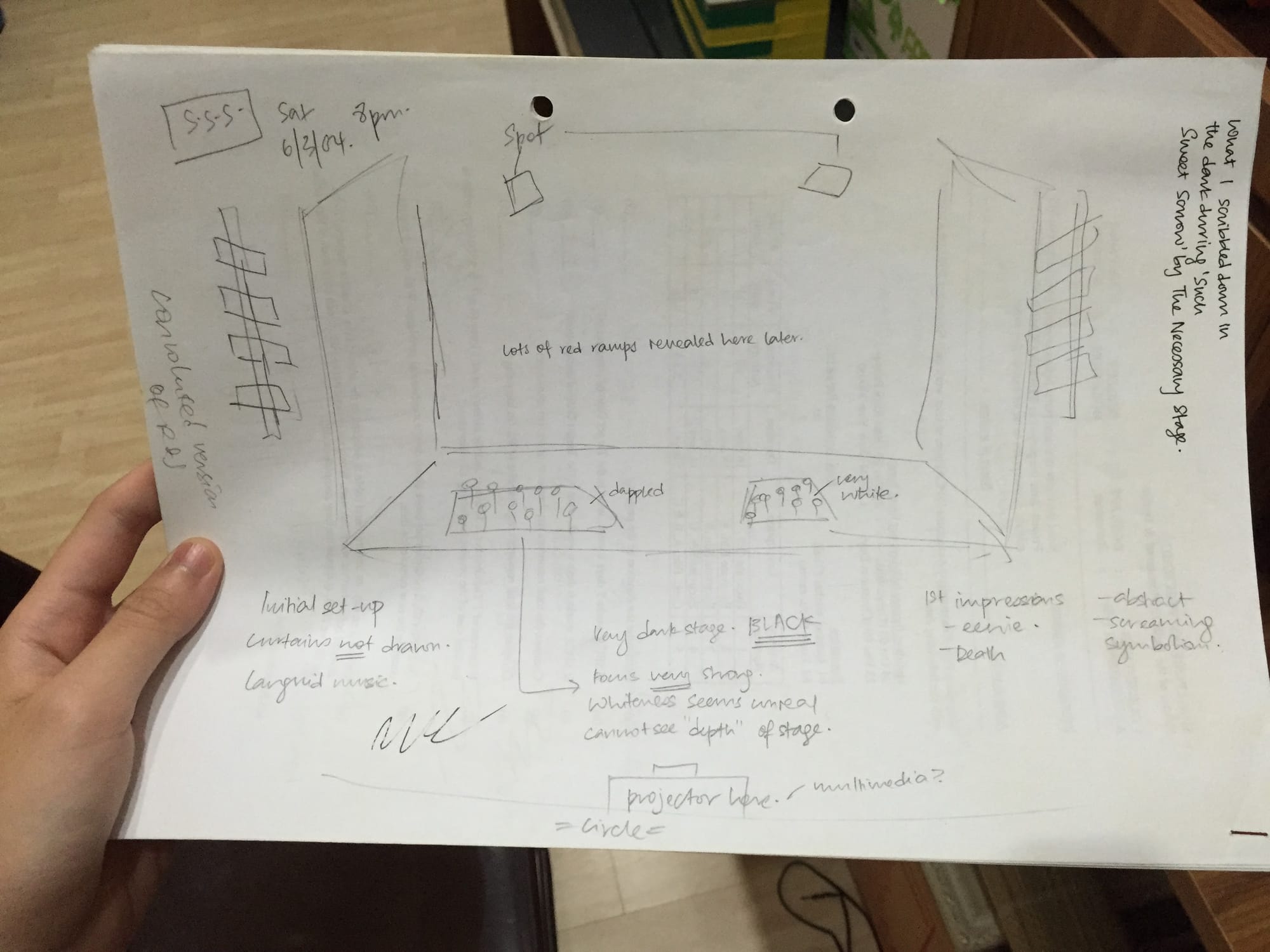

Watching the show, I wonder: what is my lineage as an arts practitioner? I was a child of the 1980s and 1990s, a mixtape millennial growing up in the faux innocence and economic complacency of a pre-9/11, pre-Enron, pre-Asian financial crisis world. As the Singaporean theatre industry was coming of age, so was I; the first local theatre production I ever watched was The Necessary Stage’s Romeo and Juliet remix “Such Sweet Sorrow” (2004), followed by their restaging of “godeatgod” (2004), created in response to the September 11th World Trade Center attacks. I was 17 and a first-year Theatre Studies and Drama student at Victoria Junior College, and took copious notes for every show I attended, even when I didn’t have to (see above). These bold postdramatic experiments marked my understanding of Singaporean theatre, set just a few years after TIME magazine’s iconic “Singapore Swings” cover: “Can Asia’s nanny state give up its authoritarian ways?” MTV Asia’s Donita Rose takes up almost the entire page. The Filipina TV presenter glances coyly at Russel Wong’s camera, her bright and blatant bubblegum stretched taut against the saturated photograph’s motion blur. My teenage theatre archives pulse with a similar technicolour energy, breathless with the possibility of breaking rules we didn’t know we had.

It’s an “anything goes” attitude that Chen, Chia and Oniatta exemplify. Or perhaps a guileless confidence not yet tempered by disappointment or failure. “I just went for auditions and did what needed to be done,” Chen says, seeming almost surprised by her own can-do approach. If their generation occupies the past perfect tense, then ours takes up the perfect continuous tense, where ongoing actions and events will only be completed at a later time. To be an arts practitioner in Singapore is to understand that you are future imperfect, non-futureproof—and yet possess some catalytic combination of beguiling naiveté and stubborn idealism that produces enough hope for the engine of another generation to keep going.

And so while theatre about theatre may seem indulgent, these processes enable a community to engage in new forms of collective introspection, bonding, and healing. The making of shared meaning is a relentless process for any group of people, and one can’t help but feel that many organisations, creative or otherwise, might benefit from the restorative rhythms of their own attempt at “Past Perfect”.

In the half-dark of Centre 42’s black box, itself a former home for a now-defunct theatre company, Action Theatre, I scrawl: “Why do we do what we do?” Loon answers my question later on: “We did not know it was not possible.” That is the beauty of our relational grammar, I suppose, that we can turn a double negative into a positive.

Corrie Tan is Jom’s arts editor.

If you enjoy Jom’s work, do get a paid subscription today to support independent journalism in Singapore.

Letters in response to this piece can be sent to arts@jom.media. All will be considered for publication on our “Letters to the editor” page.