Singapore’s election season unofficially began with the redrawn constituencies announced by the Elections Department Singapore’s (ELD) and the ensuing gerrymandering controversy. The general election (GE), to be held on May 3rd, is Lawrence Wong’s first since he took over as prime minister in May 2024. The stakes are high for the ruling People’s Action Party (PAP), after significant opposition gains in GE 2020 signalled Singaporeans’ growing appetite for plural political representation.

In the din of domestic activity, it is easy to forget that there are more than 200,000 Singaporeans living overseas. Many are deeply invested in the goings-on back home. A reported 18,389 citizens have successfully registered to cast their ballots overseas, almost three times the number of registered overseas voters from the 2023 presidential election (PE2023). Similar to PE2023, polling stations will be set up at 10 overseas missions for GE2025, in countries where a significant number of Singaporeans reside. These include the United States, the United Kingdom, the United Arab Emirates, China, Japan, and Australia. Singaporeans based abroad can also cast their vote via postal ballot, first put in place for the PE2023.

Studies of East Asian democracies have suggested that the Singapore overseas voting system is amongst the most accessible, especially after the addition of mail-in ballots. Some of the best, such as Japan and South Korea, allow their overseas citizens to vote from any overseas diplomatic mission. Taiwan, on the other hand, forces its citizens to return home to vote.

Still, a more accessible system doesn’t always lead to more voting. Korean overseas voters have relatively high abstention, citing the complexity of the electoral system (particularly as overseas voters), the lack of politically competent candidates, and doubts about the impact of their vote as the key reasons.

Many Singaporeans would agree. While compulsory voting makes it nearly impossible to abstain, apathy and inertia towards the electoral process, doubts about the integrity of the political system, and the uncertain impact of casting one’s ballot still linger. Phrases like “why does it matter” and “we already know who’s going to win” are common around election time.

One would think this to be especially true for Singaporeans who no longer live here. Not quite. Singaporean poet Jee Leong Koh, doesn’t consider voting a mandatory chore, but an important duty driven by purpose and intent. A former teacher, Koh’s dreams of being a writer led him to New York’s Sarah Lawrence College in 2003. That sparked his love for the city’s creative scene; he settled there after his graduate studies.

“There wasn’t much of a literary scene in Singapore,” he explained, alluding to the restrictions on artistic and personal expression here. As a queer man, he also cited a “repressive climate and unfair treatment of LGBTQ+ people” for wanting to pursue his masters overseas, and to later write about his experience. Yet, the attachment to Singapore remained.

In New York, he founded Singapore Unbound (SU), an organisation facilitating cultural exchanges, literary publications, and events for Singaporean and American audiences. Its flagship, the biennial Singapore Literature Festival, platforms Singapore-related literary activities. Over time, SU’s mission expanded to include discussions about pressing social and political issues within the island-city: the keynote speaker for the 2022 festival was Singaporean media scholar Cherian George. Earlier this year, SU also hosted Leon Perera, former Workers’ Party (WP) member of Parliament (MP) for a talk in New York.

“Our political turning point was [in 2017] when the National Arts Council withdrew a publishing grant for Jeremy Tiang’s ‘State of Emergency’,” Koh recalled. “While this wasn’t surprising, we felt like Singapore Unbound, being a literary organisation, should speak up on curtailing freedom of speech.” The incident coincided with Donald Trump’s first presidential term in the US, where a right-wing shift was palpable. It made Koh and his colleagues “think harder about what their political goal would be through Singapore Unbound.” Thus was born SU’s current mission statement, “to envision and work for a creative and fulfilling life for everyone through the arts and activism.”

In attempts to engage the wider Asian diaspora in the US, Koh expanded the project, and now has team members outside of NYC, USA, and even some in Europe and Australia. “Our editorial and advisory boards now include former MPs, as well as journalists,” Koh added, emphasising the importance of expert voices in making SU a more powerful voice to speak up on social issues and political developments in Singapore.

Sign up for Jom’s weekly newsletter

Our newsletters combine weekly updates about Singapore with a “build-in-public” narrative, in which we tell readers about our start-up journey.

No spam. Unsubscribe anytime.

Koh retains strong ties with the local community activists and feels the diaspora can help to effect positive changes. “We know how hard it is to do this kind of work in Singapore, and we’re relatively protected from afar, so we see it as our duty to support and amplify these calls for change.”

As before, Koh will once again cast his ballot at the overseas mission in New York this time around. “It’s important to uphold the connection,” he explained, “particularly because we have the privilege of living in another country and seeing Singapore from a different point of view.” Singapore Unbound has campaigned for overseas balloting to be more accessible, and for postal voting which finally kicked in with PE2023. Koh cited this as an important step to reduce voting barriers, benefitting both overseas voters and the democratic process.

Niranjana lives in Auckland, New Zealand, and will cast her ballot via mail. Prior to PE2023, she would have had to go either to Canberra, Australia, or fly home. She recalled her sister’s frustrating experience, who was living in Australia during GE2020 and could not cast a physical ballot at the embassy due to Covid health and safety protocols. Postal ballots are a “huge improvement in making overseas voting more accessible.” That’s just as well. Niranjana moved as New Zealand was gearing up for its GE in 2023, and the feverish electoral activity there shattered her political apathy.

“Everyone takes politics so seriously in New Zealand, mainly because it’s a very competitive system,” she explained. As a permanent resident in the country, Niranjana was initially unaware that she was eligible to vote in the local GE. Most countries, including Singapore, usually restrict suffrage to citizens. “I remember finding out I could vote about three weeks before the election, I was completely unfamiliar with [the major political parties and their star candidates] and didn’t know where to start.” Determined to participate, she talked to people around her to understand why they felt their vote was important, learning about the main political parties and their candidates in the process. Because of New Zealand’s competitive electoral system, Niranjana felt it was important for her to cast her ballot despite being a newcomer.

“Terms only last three years here and you really see the lead-on effect once another party is elected and gets to undo everything the previous administration did,” she said. Her voting experience in New Zealand instilled in her the importance of dialogue and exchange across political affiliations, something she believes is lacking in Singapore’s political discourse. “Both sides have been quite ugly, lots of things politicians are doing feel very disingenuous, with more emphasis on saving face while throwing the other party under the bus than engaging with the people.”

She feels this hinders the constructive political dialogue that opens up space for new voices. As such, she is more determined than ever to cast her vote. Her home constituency, Sengkang, is currently held by the opposition WP which won 52 percent of the vote in GE2020. It is expected to be one of the closest contests of GE2025 too. “My family still lives [in that GRC], the election and policies will affect them and other people who matter to me, it’s still important to be able to cast [it] in a battleground GRC,” she told Jom.

Elouise Quek, a Singaporean graduate student based in Paris, France, echoed Niranjana’s determination when speaking of her decision to register to vote at the Singaporean embassy in London. “It feels like a real commitment as a [Singaporean] citizen to be making that journey to exercise my democratic right, particularly as this will be my first time voting as well,” she said, when we first spoke.

But Nomination Day sprang a surprise. No party will contest against the PAP in the newly fleshed-out Marine Parade-Braddell Heights GRC—Quek’s constituency—which was considered one of the key battlegrounds following opposition gains in the past three GEs. The National Solidarity Party won a stunning 43 percent of the vote in 2011. In 2015, the WP won 36 percent, and improved to 42 percent in 2020.

When we spoke again, a disappointed Quek acknowledged that the GRC is “now in an unrecognisable shape”, referring to the Electoral Boundaries Review Commission’s extensive changes earlier this year. She understood the party’s “strategic choice” to shift focus to other key GRCs, like Tampines, which will host Singapore’s first ever four-way contest.

Quek feels new slates of accredited politicians with diverse voices and community-oriented politics have made the opposition a viable alternative. “The Opposition is nothing but resilient, I’m still looking forward to the outcome of this year’s election,” she shared.

Quek’s insights on Singapore politics and popular sentiment stem from her work with Wake Up Singapore (WUSG), an independent volunteer-run platform that publishes news reports on their website, as well as social commentary on their social media pages, particularly Instagram. She got involved after meeting Ariffin Sha, the founder, who was recently unveiled as a member of the Singapore Democratic Party (SDP) team that will contest against the Wong-led PAP squad in Marsiling-Yew Tee GRC.

“I could relate to his vision [at WUSG], we share similar values and both believe in fostering political and media literacy through not just consuming but also producing political content in ways that are safe and well-informed,” she explained.

She emphasised WUSG’s role in making debates more accessible to the general public, The platform often juxtaposes claims made by politicians in Parliament with details on how these issues play out in reality, as was recently the case when Amy Khor, senior minister of state for transport, stated that banning lorry rides for migrant workers was “not practical,” and could force smaller firms to shut. Khor was criticised for dismissing migrants’ safety and well-being.

“It’s a very precious thing to have a platform for the masses, especially in Singapore [where there are] few spaces for such a public forum,” Quek said. Much like Niranjana in New Zealand, her views on making politics accessible were shaped by exposure to French politics, and the contrast between state and civil society relations in France and Singapore. She thinks some Singaporean elected officials’ refusal to engage in difficult political conversations, such as POFMA or Singapore’s position on Gaza, risks ostracising citizens from important social and political issues.

“Politicians [in France] are much more willing to discuss complex political topics with the people, and they don’t infantilise them in doing so,” she noted.

Take Khor’s controversial statement on lorry rides for migrant workers. It is representative of the government’s reluctance to address an issue that has been at the forefront of conversations with advocacy groups for years. Another example is the time Vivian Balakrishnan, foreign minister, asked: “Do you want three meals a day in a hawker centre, food court, or restaurant?” Balakrishnan was responding to Lily Neo, then-MP for Jalan Besar GRC, who wanted public assistance recipients to be given enough to afford three hawker centre meals a day. Quek pointed to PAP’s Louis Ng, WP’s Jamus Lim, He Ting Ru, and Pritam Singh, and SDP’s Paul Tambyah and Chee Soon Juan as the few politicians earnestly engaging with everyday citizens, willing to accommodate more difficult policy conversations.

Similarly, her understanding of civil society’s role and capability greatly benefitted from her time in Paris. “I see frequent protests with huge droves that go, for the most part, very smoothly, with very few instances of police crackdown,” she said, in another stark contrast with Singapore’s civil society, which is often seen by the authorities as “an affront to the state rather than a [positive] symbol of political expression.”

Just like Koh and Singapore Unbound, she considers the Singapore diaspora crucial in helping facilitate this change at home, where the state exerts stronger control over channels of resistance.

The diaspora’s role also animated my conversation with Sumithri Venketasubramanian, who left in 2016 to pursue a Bachelor’s in Canberra, Australia, and has resided there since. She was temporarily forced home during the Covid-19 pandemic and during GE2020. Her sense of helplessness, coupled with the pandemic which cast a light on Singapore’s growing inequalities, particularly for migrant workers, compelled her to volunteer with the WP in its Aljunied GRC stronghold.

“There was a real opportunity to have genuine representation for the opposition, and to challenge the one-party state assumptions,” she shared. Ahead of the upcoming election, she once again feels this sense of hope. “Many of my friends [in Australia] have asked me why I’m so excited to vote, and whether my vote even counts at all, and I took it upon myself to educate them on Singapore’s vibrant multiparty system in the pre-independence era before the shift to PAP dominance,” she said.

In her view, the aftermath of GE2020 opened the door for a rebirth of political pluralism in the island-state. The PAP scored only 61.24 percent of the vote, the lowest since independence, and WP chief Singh was appointed the official leader of the opposition—a consequential, even if ceremonial, move: “It shows that there is a shift happening in politics, whether PAP accepts it or not, it’s a clear acknowledgement of Singaporeans’ desire for other voices in Parliament.”

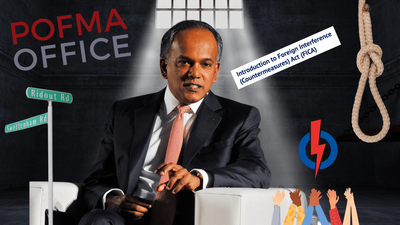

She emphasised the significance of this shift in light of Singaporeans’ reputation as apathetic individuals, showing that citizens aren’t merely content with the PAP, and are demanding more from their politicians. Singapore’s potential has been “limited by the actions of one political party, through tools like the Public Order Act, POFMA, or FICA,” but Singaporeans remain deeply political at their core.

In fact, there’s more than just voting for more opposition voices in Parliament. Instances of public solidarity and mutual aid during the Covid-19 pandemic, as well as growing attendance at public gatherings such as Pink Dot and Labour Day Rally further validate Venketasubramanian’s point that Singaporeans are more political than they are often credited for. What is perhaps truer is a difference between Singapore and the rest of the world on what constitutes a politically active citizenry. The current legal framework might make it impossible for Singaporeans to take to the streets, but that doesn’t mean they don’t have an inclination for political change.

According to Venketasubramanian, the diaspora can help challenge preconceived ideas foreigners might have of Singapore, pushing back against the PAP-driven narrative. She brought up an Instagram post shared by the World Economic Forum earlier in February, portraying Singapore as an ecological utopia with lush and abundant green spaces. This vision is very much in line with how international and foreign media outlets paint the city-state, emphasising the overall success of the PAP’s public, economic, and environmental policies.

This narrative also lionises Singapore’s founding father Lee Kuan Yew, praising his iron-fisted leadership and often ignoring his authoritarian stance on social issues, disregard for individual freedoms, and his controversial views on race. It also omits how Singapore maintains its reputation as a green utopia by depleting the natural resources of neighbouring countries—importing sand from Indonesia, and buying carbon credits from Cambodia.

The “garden city” is one of many stereotypes that Venketasubramanian has challenged when discussing Singapore with her Australian friends. Similarly, she spoke about how Singapore’s public housing system has come to be revered around the world as a wonder of public policy, with few aware of the growing inequalities within that system.

“As a queer person myself, I had to tell my friends [in Australia] that I can’t buy public housing, and can only apply to rent until I’m 35, because I can’t get married in Singapore,” she explained. She also discussed the rising costs of Housing and Development Board (HDB) flats. Policies enacted in the last few decades have put the government in a bind: if the prices drop too much, older generations’ “nest eggs” will be destroyed; if they keep rising, younger ones like Venketasubramanian won’t be able to afford them. In this, as in everything else, Venketasubramanian hopes to provide her foreigner friends with a more realistic understanding of Singapore, one that also makes sense of her desire to advocate for political change at home.

“As Singaporeans, we’re often taught to think patriotism is never criticising Singapore, but real love for the country is wanting to improve society.”

Robin Vochelet is a freelance writer and multimedia journalist based between Singapore and Bangkok, covering civil society, social movements, queer identities, and subcultures across South-east Asia. He also writes Pandan Brief, an online newsletter discussing social, political, and cultural trends in the region.

Letters in response to this piece can be sent to sudhir@jom.media. All will be considered for publication on our “Letters to the editor” page.

If you enjoy Jom’s work, do get a paid subscription today to support independent journalism in Singapore.