Over a thousand homeless people. Middle-class professionals losing their jobs, and then forced to queue at soup kitchens. Some 30 percent of working households earn less than the amount required to meet basic needs. Old aunties and uncles cleaning tables, sweeping streets, doing manual labour till the very end, their hunched backs an indictment of the system.

This isn’t some faraway backwater, but Singapore, our home. How is it that we’re also one of the world’s richest cities?

Inequality is arguably the most important big-picture issue at stake in the upcoming general election (GE). It’s important to first understand how bad it is, then interrogate the capitalist’s mindset that might explain our stratified economy, and finally examine what the opposition is proposing to do about it, and the trade-offs involved.

How bad is income inequality? After taxes and transfers, it’s already high for the developed world. But it’s probably far worse than we know. As Jom has detailed, Singapore uses a suspect method of measuring it. The biggest problem is that unlike other countries, Singapore does not include income from investments in its measure, only that from work. This greatly underestimates the incomes of the rich, many of whom earn far more from their investments than their wages.

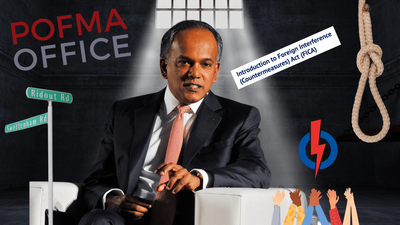

Consider the recent sale by K Shanmugam, law and home affairs minister with the ruling People’s Action Party (PAP), of a good class bungalow for S$88m dollars. That phenomenal investment return—he seemingly bought it in 2003 for around S$8m—would not be a data point when Singapore measures income inequality. Or think about private equity managers, who typically make far more in “carried interest” and other investments. Or the scores of crypto wizards who’re attracted by our laissez faire regime, or the wealthy landlords, of old and new money, scattered across town.

Singapore, astonishingly, now has more millionaires than London, a much bigger city. By failing to account for their investment income when measuring income inequality, we blind ourselves to its dangers. As far back as 2018, Ng Kok Hoe of the Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy criticised the incomplete measure. I’ve also had interactions with officialdom on this point, without satisfactory explanation. My guess is that we don’t measure it because a true apples-to-apples comparison with other countries would be terribly embarrassing. Any suggestion that it’s not possible to measure or estimate it is laughable in a surveillance state. (To be fair, given that we’re a city-state, perhaps the more relevant inequality comparison would be to, say, London rather than the UK.)

So Singapore doesn’t measure income inequality well, making it seem like we are more equal than we actually are. And we don’t even bother measuring wealth inequality, which compares assets rather than income.

Thankfully, others do. UBS said that from 2008 till 2023, Singapore’s average wealth rose an astonishing 116 percent, even as our median wealth—the person in the middle—dropped two percent. Singaporeans in higher wealth brackets have been “booming”, while everybody else has “essentially stagnated”, UBS said.

One favoured defence of this hierarchical system is social mobility. People like Lawrence Wong and Shanmugam, so it goes, came from humble beginnings and were able to rise to the top. That’s true. If you have the right genotype and phenotype, if nature and nurture have blessed you, then yes, the Singapore system will allow you to succeed.

But what about everybody else?

Sign up for Jom’s weekly newsletter

Our newsletters combine weekly updates about Singapore with a “build-in-public” narrative, in which we tell readers about our start-up journey.

No spam. Unsubscribe anytime.

In The Burning Earth, historian Sunil Amrith offered a rich depiction of the capitalist’s mindset. He examined the dire conditions facing gold miners in early 20th century South Africa. Mine owners wanted to offer their workers just enough air for them to breathe.

“…The mine owners of the Rand made the same calculations that shipowners had made two centuries earlier as they outfitted vessels to transport enslaved Africans: How much air did a person need? What was the minimum ‘air space’ they could get away with providing a human being?”

To be sure, living conditions in Singapore, even for our low-wage migrant workers, are infinitely better. But the capitalist’s mindset is similar. The regular complaint now is with the quality of nutrition. We don’t subject our migrant workers to minimum “air space”, but maybe minimum “calories”.

For workers in low-wage sectors, as economists Linda Lim and Irene Ng say, “their absolute and relative wages continue to be significantly lower here than in other rich countries”. Singaporeans may not immediately resonate with the traumas of migrant workers, but it’s important to understand that in the unjust system, this is the worker baseline, above which all others are determined. In our first world country with a third world wage structure, this minimalism affects not just those at the very bottom.

Low-wage construction workers seem to exist in a parallel universe, in conditions that no Singaporean would tolerate, whether in lorries or dorms. Above them in the Darwinian pecking order, Singaporean cleaners earn wages that might only afford them food and shelter. Those in the “sandwich class”, meanwhile, are kept constantly on the edge of financial precarity, their grants and handouts tweaked. This is the hunger, the desperation, that capitalists believe drives the rat race. Once in a while they might have to seek help from their member of Parliament, entrenching the dependency and the patronage. “A rich country shouldn’t have so many poor citizens—proportionally, Singapore has twice as many poor citizens as OECD countries, other rich countries,” Lim has separately written.

Exploitative, profit-maximising capitalists consider individual workers to be factors of production, digits, not individual human lives. In other democracies there are many forces reining them in, including the media and the opposition. Unlike the South African racists, our Singaporean leaders genuinely care for those at the bottom, there should be no doubt about that.

But the problem has to do with the PAP’s ideological inertia, its neoliberal dogmas, which have gone unchecked for 60 years. From the 1950s-70s the PAP went from championing the worker’s rights to championing the corporation’s. Part of that involved neutering labour unions, so we wouldn’t have pesky workers bargaining for better wages and rights. Singapore’s subsequent rapid, if terribly unequal, economic development was partly attributed to this, becoming part of the lore. The power dynamic today between company and worker here is more similar to a Middle Eastern monarchy than a modern democracy.

To further appreciate all this, consider the government response to the Minimum Income Standards (MIS) Study. This is work initiated and led by sociologists like Teo You Yenn and Ng. (Disclosure: Teo is an endorser of Jom.) They interviewed Singaporeans to find out about their basic needs, and suggested seemingly modest MIS budgets, for instance S$6,693 for a couple with two children aged 7–12 and 13–18 years old. They found that some 30 percent of working households earn less than the amount required to meet basic needs. Policy recommendations included a “living wage, a universal wage floor”.

But three ministries rebutted them in a joint response. One of their complaints was around the definition of needs. They said small purchases of perfume and jewellery, which perhaps might help somebody present themselves better at interviews, were not “needs”. Neither was a four-day trip to Ipoh and Port Dickson by bus. In truth, this issue probably divides a lot of Singaporeans in terms of social justice. Do people at the bottom deserve more than just food, shelter and basic healthcare? Your view on that might actually inform your vote.

To be clear, all this is not to suggest that the PAP ignores the less fortunate. Lee Hsien Loong’s administration launched a slew of socio-economic programmes, from the Progressive Wage Model (PWM) to the Pioneer, Merdeka, and Majulah packages, which together arguably went further in terms of social spending than any previous one. The point, rather, is one of relative scale. The party has been seemingly far more successful in attracting the world’s rich and helping them grow their wealth.

Unlike the PAP, the opposition believes that inequality is a big problem, that the spiralling cost of living is a generational crisis, which can’t be solved by the dripfeed of handouts, but through a longer-term structural change in circumstance. Let’s just look at two broad opposition proposals: a minimum wage; and greater use of our reserves for social spending.

The opposition has argued that the PWM isn’t doing enough, and what’s needed is a minimum wage. The common rebuttal to that is that it’ll affect businesses and lead to job destruction. Unemployment will go up. Academic evidence on this point is mixed. In some cases, a minimum wage has led to job losses, in others not really. A lot really depends on how carefully it’s calibrated and introduced.

We don’t quite know what will happen in the Singaporean context. Perhaps there might be some short-term pain for some businesses. But in the longer-term, they’ll surely adjust, and succeed, as do companies in many places where wages are higher.

In “A Universal Minimum Wage for Singapore: an idea whose time has come”, Lawrence Pek, candidate with the Progress Singapore Party (PSP), and Leon Perera, a consultant and PSP volunteer, deal with a lot of the common objections. Pek runs a factory in Shenzhen, China that manufactures high-end surveillance cameras, whose 150-200 odd workers, depending on production, depend on a minimum wage.

At his opening rally speech, Pek said he’d initially questioned the Chinese local government about the need for a minimum wage. Their response was that it protects employees from demanding and unscrupulous employers; and that it’s needed to keep up with inflation. Jeffrey Siow, part of the PAP team that Pek is up against, criticised Pek’s desire for a minimum wage as more political than practical. Should the voter trust the candidate who’s been in the trenches or the one whose only prior job was in the elite civil service? Again, your view on that might also inform your vote.

What about the greater use of our reserves? For one, nobody outside the PAP (and presidency) knows how big it is, so we can’t accurately assess the impact. Conservative estimates put it at well above a trillion dollars. More importantly, the PAP itself says there’s no magic rule to its current 50-50 formula: spend half of the returns today, save half for tomorrow. The PAP says that it’s saving for a rainy day, but many Singaporeans believe it’s already pouring. Jom gets into this more in this piece on CPF and reserves, including the suggestion that reserves must be hidden to deter currency speculators.

Capitalists everywhere will scare you with the slippery slope argument. More redistribution, and before you know it, we’ll become a welfare state where nobody has any motivation to work. But no opposition party is asking for a radical shift. For instance, the WP suggests shifting the 50/50 formula to 60/40—spending 10 percent more of the returns now, without touching the principal amount. Other calls include the PSP’s suggestion to lower the GST, but perhaps fund the shortfall through estate taxes or small wealth taxes on the ultra rich. These are small movements in the direction of greater equality.

For sure, the opposition isn’t coming to power anytime soon. But your vote will make a difference on inequality, both as a signal to the PAP, and if more elected opposition MPs are able to argue the case. It’s not just those at the bottom who’re concerned about inequality; many of the rich are too, because the potential for serious class conflict is growing by the day. Recent May Day rallies at Hong Lim Park have drawn everybody from delivery riders to nurses and doctors, with some railing against those who live in good class bungalows.

By contrast, if you still have faith in the PAP’s neoliberal philosophies, and believe that society progresses when businesses are unshackled from workers’ demands, and that the profits should mostly flow to those at the top, then there’s one good reason to vote for the PAP. And make no apologies for it, it’s a valid and different worldview, one shared by many millionaires and billionaires around the world. And therein lies a different strand of the rich, those who glorify “cheap hawker food” and “cheap maids”, those for whom inequality is a feature, not a flaw.

A vote for the PAP is a vote for its neoliberal, growth-at-all-costs approach that involves, among other things, high immigration, attracting MNCs and millionaires through a low tax regime, a belief in trickle-down economics, and minimal redistribution. A vote for the opposition is a push towards a more equal society, that’ll involve, among other things, more redistribution, and better protection for workers, as part of an overall shift in power from corporations to workers. But among the trade-offs are restraints on the ultra-rich and the extra dipping into our reserves.

Voters should contemplate the future they want, and make an informed decision.

Sudhir Vadaketh is Jom's editor-in-chief.

If you enjoy Jom’s work, do get a paid subscription today to support independent journalism in Singapore.

Letters in response to this piece can be sent to sudhir@jom.media. All will be considered for publication on our “Letters to the editor” page.