In Rodham, a novel imagining an alternate life for Hillary where she doesn’t marry Bill Clinton, Curtis Sittenfeld brilliantly captures the inherent sexism women face in politics.

In one exchange where Hillary is preparing with her team for a presidential debate, her coach asks, “Have you ever seen someone with a facial tattoo?”

“People who attend your events are self-selecting and largely predisposed to like you. But whenever you’re on TV, imagine you have a huge tattoo across your face. You’re discussing healthcare, and people can hardly listen because they’re so busy thinking, ‘Why did she get that tattoo?’ That’s how unfamiliar voters are with a woman running for president.”

Unconscious biases shape us all, but few are as damaging as the notion that women lack the ambition, ability, or strength to lead—in business, government, or even the country. The more women we see in leadership positions, especially in the highly visible political realm, the faster we can dismantle these beliefs.

With the passage of the Women’s Charter in 1961, a landmark law that underpinned the broader emancipation of women, many may have been hopeful that equal representation in politics and business was round the corner.

But progress is not always linear, or a given. Following the retirement in 1970 of Chan Choy Siong, member of Parliament with the ruling People’s Action Party (PAP) and a key advocate for the Women’s Charter, Parliament became all-male and remained so for the next 14 years. This was the period, incidentally, when the government introduced many controversial policies that directly impacted women, without any input from them. It interfered with deeply personal choices of childbirth and marriage, offering financial and social incentives for non-graduate women to undergo sterilization while introducing the Graduate Mothers’ Scheme to encourage highly-educated women to marry and procreate.

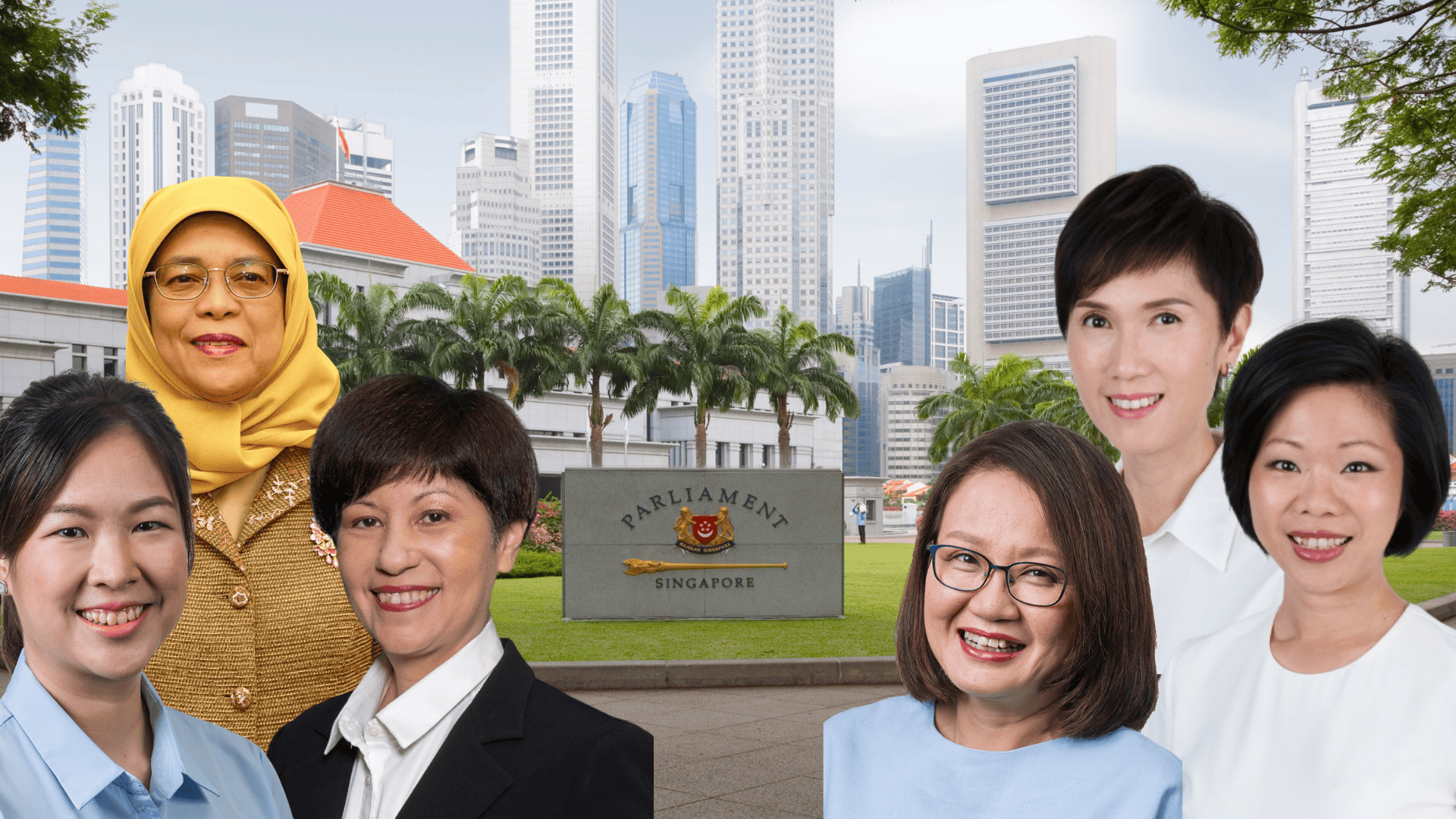

In 1984, three women entered Parliament with one more joining them in 1988. This still made up just five percent of all elected members. After the 2020 general election, that number rose to 29 percent (including nominated members), slightly above the global average of 27 percent. Significant progress, but we can go much further. Only three out of the 19 cabinet members are women, for instance; only two helm a ministry.

Sign up for Jom’s weekly newsletter

Our newsletters combine weekly updates about Singapore with a “build-in-public” narrative, in which we tell readers about our start-up journey.

No spam. Unsubscribe anytime.

Sylvia Lim, Workers’ Party (WP) chairperson and an elected MP since 2011, spoke in 2021 about female representation in political leadership. Female candidates, Lim observed, are “burdened with worry and even guilt” about how their political careers will impact family responsibilities. This is made worse by pressure from parents, in-laws, and even employers who question how they would juggle it all. Despite being as qualified as their male counterparts and as interested in public service (evidenced by the high number of female volunteers and members political parties are able to attract), many are unable to “freely decide whether to stand as candidates, compared to males who seem to have fewer inhibitions.”

Her parliamentary colleague, He Ting Ru, separately argued that it is “women who bear a disproportionate share of unpaid labour, both tangible and ‘invisible’ in the form of the mental load, because it is still usually the woman who is expected to oversee the smooth running of our households”.

He’s observations are echoed by Teo You Yenn, sociologist at the Nanyang Technological University. Teo has empahsised the importance of choice and autonomy, of creating social norms and conditions that give women optionality because, just like men, they do not all want the same things from life. Freedom from the necessity of caregiving and running the household would allow those so inclined to pursue careers of their choice, including political ones. “The current situation of inequality-where some women’s choices are valorised and other women’s choices are judged and frowned upon…must be disrupted…” she wrote. You Yenn’s research is cogent, actionable and rooted in the idea of equity. And yet, some of our politicians continue to perpetuate outdated and sexist stereotypes.

When running for president in 2011, Tan Cheng Bock, a former PAP MP, said in response to a question about how to encourage female participation in politics: “The political arena is a difficult area for women in Singapore because the commitment is really very heavy. So you got to get the permission of your husband.”

Also in 2011, 33-year-old PAP candidate for Hougang (and current MP for Tampines), Desmond Choo recounted how an old constituent told him that choosing an MP is like choosing a wife: “If your wife is unable to cook, there’s no point. You must choose a wife who is able to do things for you.” The words may not have been his but the fact that Choo used them to woo voters—presumably by claiming he would “do things” for them as a wife does for her husband—showed the durability of gender roles and biases, and how easily they can be passed down through generations.

More recently, PAP MP and chair of its Women’s Wing, Sim Ann, was called out for reinforcing such biases during an interview where she commented that “by allowing young couples to apply for Housing Board flats, women learn to run their own households from young.”

While policies have evolved—such as the recent increase in government-paid paternity leave and a new 10-week shared parental leave scheme—our thinking has not kept up.

Most disappointing, however, was how we got our first female president. Halimah Yacob, Singapore’s first female Malay MP, first woman to become speaker, and first Singaporean to be elected to the International Labor Organisation’s governing body, won uncontested. The reason? In 2016, the constitution was amended to reserve the election for a candidate from a racial group that has not occupied the president’s office for five or more consecutive terms. This was done right before the 2017 presidential election, which then became reserved for Malay candidates. Many perceived this as a political manoeuvre to exclude Tan from competing again. (“Tan Cheng Block” was the cry.)

Now imagine, if the 2017 elections were not reserved and Halimah ran and won anyways. She would have become the first elected female and first Malay president. The glass ceiling for women would have been shattered. Six years later, Halimah had a chance to stand for re-election in an open contest, but she declined, despite her popularity. The PAP perhaps feared she might lose to a Chinese man. Instead, Singapore’s most loved politician, Tharman Shanmugaratnam, stepped up and broke a different kind of ceiling. His decisive victory over two Chinese men in a national election has cast doubt on whether the reserved presidential election scheme—controversial from the outset—was ever necessary.

Seeing is believing.

The private sector too leaves much to be desired. The Straits Times (ST) recently reported that female chefs are better supported in a traditionally male-dominated industry. “Increasing acceptance of female chefs is in part the result of years of consistent, if arguable repetitive coverage,” Debbie Yong told ST. Yong runs Turn The Tables, a podcast on female leadership in the hospitality industry. Despite the changing norms though, of the 47 Michelin-starred restaurants here, only one is led by a woman: Fernanda Guerrero, who co-runs Chilean outlet, Araya, with her partner. Better representation at the top is needed to inspire the next generation of female chefs so they can aim higher and compete with the men head-on.

Seeing is believing.

Another ST feature highlighting Captain Vanessa Khaw’s journey from the cabin to the cockpit revealed the dearth of female pilots we have in Singapore. Of the over 3,000 pilots that SIA and Scoot have, only 61 or 1.9 per cent are female. This is unsurprising given SIA only started accepting female cadet pilots in 2016, possibly the last major global airlines to do so. As Mabel Kwan, vice-president of Women in Aviation (Singapore chapter), explained “many young women may be unaware of the viability of pursuing a career as a pilot, or do not know about the pathways they need to take to become a pilot.” Captain Khaw too credits female role models who showed her that it was “actually possible” for women to become pilots.

Seeing is believing.

A recent survey of 30 countries found that 57 per cent of Gen Z males think feminism, which advocates for equal (not more) rights, opportunities, and representation for women, has led to unfair discrimination against men. Political leaders like Donald Trump, US president, have fuelled this distorted worldview and legitimised the misplaced grievances of young men. Trump’s sexism-laced comments led to a surge in online attacks against both Clinton and Kamala Harris during the 2016 and 2024 presidential campaigns respectively.

Young men here are also expressing such troubling viewpoints online in the so-called manosphere, where sexism and misogyny is rampant. Women have become easy scapegoats for what is actually a crisis of masculinity and the deeper problems men face—social isolation, poor mental health, financial insecurity. Even more alarmingly, seemingly well-adjusted, accomplished men can parrot bigotry too. The recent incident where the Law Society’s vice-president spread harmful rape myths and engaged in victim-blaming a rape survivor was a stark reminder that for all the progress we have made on gender equality, we have a long way to go still.

Even before a contest is declared and candidates are named, the odds are stacked against any woman seeking a position of power, especially in politics. In her book Entitled, How Male Privilege Hurts Women, Kate Manne highlights research showing that, time and again, people, regardless of gender, tend to assume that men in historically male-dominated positions of power are more competent than women. This could be one of the reasons why 45 percent of American women voted for Trump in 2024, despite his appalling sexist behaviour and views.

Women who seek power are expected to embody “communal” traits—nurturing, sensitive, kind, sympathetic, and understanding— on top of demonstrating competence. Meanwhile, male politicians, including widely admired figures in the US like Bernie Sanders and Joe Biden, face little consequence for being “abusive”, “short-tempered”, and “downright hostile” toward their own staff.

In power, women are often expected to prioritise social policies or be more proactive on women’s issues such as female healthcare or gender-based violence. Indeed, there is some evidence to suggest that having higher numbers of female leaders leads to legal equality of economic opportunity (e.g. protection against workplace discrimination). But narrowing the mandate for female politicians can itself become an unfair burden.

Research has shown that simply having a “critical mass” may not lead to pro-women outcomes. Legislative structures, party affiliation, and individual agency matter too. In Singapore, female politicians have also had to downplay their gender or “feminine identity to avoid being stereotyped and marginalised as token figures in politics. In a recent ST interview, Lim, the WP chairperson, said she felt pressured by some to speak up on women’s issues. “I told them: ‘Look, I’m a party leader. I cannot be pigeonholed into just women’s issues. I will not be making a fair contribution that way’”. Men rarely have to worry about such things, she added pointedly.

When there are only a handful of you, every move is scrutinised.

The upcoming General Election (GE) is an opportunity to challenge harmful gender stereotypes head on–by sending more women to Parliament. One way would be for the major political parties to field at least one female candidate in each Group Representation Constituencies (GRC) they contest. In GE 2020, for instance, PAP, which contested all GRCs, fielded all-male teams in three – Marine Parade, Bishan-Toa Payoh, and Sengkang.

Reimagining GRCs to support female politicians, along with minority races, would not only send a strong message to the electorate, but could also lead to more women in Parliament and Cabinet. It is worth noting that having lost Sengkang to a mixed-gender WP team, the PAP has announced a more gender-balanced team this time.

We have come a long way since the controversial Graduate Mothers’ Scheme was announced in 1983. While it was quickly reversed following a fierce public backlash, including from graduate women themselves, other fights for equal rights have taken longer. For instance, until 2004, children born abroad to Singaporean mothers did not automatically receive citizenship by descent—the privilege was exclusively reserved for Singaporean fathers.

In 1979, the government announced a one-third cap on female enrolment in medicine at National University of Singapore (NUS). Toh Chin Chye, then health minister, claimed that their wifely and motherly duties made it tough for women to be good doctors, that they were “choosy” and keen to get back home as soon as possible.

It wasn’t until 2002 that the cap was lifted, after years of protestations inside and out of Parliament. In 2024, NUS enrolled its largest ever proportion of women in medicine: 60 percent.

Seeing is believing.

Each of these fights for equality has been long and arduous, but they are all worth having so that the next generation of girls and women can live in a world where they have equal rights to boys and men.

Not more. Not less. Equal.

In Rodham’s alternate reality, Hillary, having become president, reflects on whether the miracle was not her successful election, but how quickly it came to seem ordinary. She thinks to herself “Now other women know they, too, can make it, and not because I or anyone else tells them.

They know because they’ve seen it happen.”

Seeing is believing.

Chirag Agarwal is a former civil servant and public policy consultant. He is now the co-founder of Talk Your Heart Out, a Singapore-based therapy platform.

Letters in response to this piece can be sent to sudhir@jom.media. All will be considered for publication on our “Letters to the editor” page.

If you enjoy Jom’s work, do get a paid subscription today to support independent journalism in Singapore.