Editor’s note: These views are Harpreet’s, not Jom’s. We’re not endorsing any party in the upcoming election. We’ve in the past invited other politicians, including Hazel Poa, Paul Tambyah and Lawrence Wong, to publish commentaries here. We’ve also just asked the PAP for a response to the below, either as a commentary or letter, which we’d happily publish.

For decades, Singapore has been heralded as an economic and governance success story—a city-state that punches far above its weight in global finance, trade, infrastructure and urban planning. Its leadership has been widely credited with driving a model of stability, efficiency, and long-term planning that has seen the country flourish. Yet, as we head into a critical general election, our country faces a moment of reckoning. Beneath the veneer of prosperity, pressures are mounting: housing costs have surged, job insecurity is growing, birth rates are continuing to plummet, and the rising cost of living has put the financial security of many households under increasing strain.

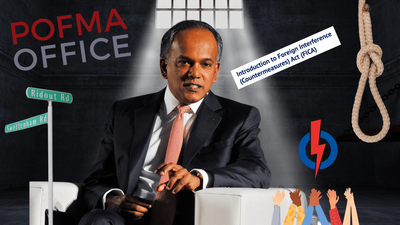

This election is about more than just giving Prime Minister Lawrence Wong his first electoral mandate since taking office. The real question before voters is whether we should allow the People’s Action Party (PAP) to continue governing with an overwhelming parliamentary majority—or whether we should push for a more balanced system by electing a stronger opposition. Far from introducing instability, the latter would signal a necessary and overdue evolution in Singapore’s governance model: a shift towards greater accountability, policy innovation, and a politics that is more responsive to the real challenges our people face.

Sign up for Jom’s weekly newsletter

Our newsletters combine weekly updates about Singapore with a “build-in-public” narrative, in which we tell readers about our start-up journey.

No spam. Unsubscribe anytime.

Singapore has long operated under a governance structure where the PAP dominates, shaping nearly all aspects of policy with little effective resistance. While this has allowed for long-term planning and rapid policy implementation, it has also meant that important national debates often remain tightly managed, limiting the space for deeper scrutiny.

Now, however, our country faces a new and more complex set of challenges—ones that cannot be tackled simply by minor policy tweaks or financial handouts.

Housing costs, once an area of pride for the government, have become a source of anxiety. The affordability of public housing—built on a model that assumes households with stable long-term jobs—looks increasingly fragile in an era where automation, AI, and shifting economic and geopolitical trends are impacting employment stability and income security.

At the same time, both the job market and the nature of work are evolving in ways that require a fundamental reassessment of policies originally designed for a different era. The rise of the gig economy, corporate restructuring, and the increasing displacement of traditional white-collar jobs are disrupting the long-standing assumption that Singaporeans can expect stable, long-term employment. For a country where home ownership and CPF retirement savings are structured around the expectation of consistent, long-term income, these changes pose significant risks.

Meanwhile, our education system appears increasingly misaligned with a future that prizes creativity, adaptability, and risk-taking. Despite years of reform efforts, Singapore’s students remain under immense pressure and fixated on exam performance, while employers lament the lack of graduates equipped for the demands of a global, innovation-driven economy.

Most worrying of all is our demographic decline. Singapore’s total fertility rate has dropped to record lows, and many young Singaporeans are contemplating moving abroad in search of a better life. Left unchecked, these trends will result in an aging society where a shrinking workforce is expected to support a growing elderly population—an unsustainable economic trajectory. Increased immigration is, at best, only a partial answer. It must be complemented by deeper structural reforms.

The challenges Singapore faces are not insurmountable. In fact, our country is better positioned than most to tackle them. Unlike cities such as London, New York, or Sydney, Singapore’s government owns 80–90 percent of the land—giving us a rare degree of control over public housing affordability. Our reserves, conservatively estimated at over S$1 trillion, provide an extraordinary fiscal cushion that can be leveraged to invest in long-term national priorities without endangering financial prudence. And we have a deep talent pool, both within and outside of our first-rate civil service, capable of driving world-class solutions.

Yet, despite these advantages, the government appears to have resisted bold reform. Instead, it has preferred incremental policy adjustments and deploying financial assistance schemes and voucher programs that do little to address the underlying structural problems. This inertia is not due to a lack of competence within the civil service or a lack of national resources—it is the result of our overcentralised political system that has narrowed the space for fresh policy ideas to gain traction, curbing the depth of policy debate.

This is why a stronger opposition in Parliament is not just desirable—it is necessary.

Some argue that Singapore’s one-party dominance is key to our continued future success. But history suggests otherwise. Many of the world’s most effective governments operate with a strong opposition that ensures policies are rigorously debated, stress-tested, and refined before implementation. In Germany, Japan, Canada, Australia and in the Nordic countries, opposition parties do not weaken governance; they enhance government by fostering accountability while ensuring that a diversity of ideas leads to better, more well-rounded policy decisions.

Singapore’s opposition is not calling for revolutionary change, nor does it seek to upend the foundations of the country’s success. Instead, we are advocating for a course correction—one that prioritises affordability, greater financial security of our citizens, and a more open and dynamic society that embraces those outside the political mainstream.

A stronger opposition could help push forward several policies. These include, first, a rethinking of HDB policy to ensure that housing remains affordable and accessible in an era where long-term job and income security can no longer be taken for granted. Second, a realignment of CPF and retirement policies to provide greater financial security for our seniors. Third, a national unemployment insurance scheme to support workers in an increasingly unpredictable job market. Fourth, a serious reform of education—reducing the emphasis on high-stakes exams and shifting towards a revamped curriculum that prepares our students for the world of the future. And a fairer, more transparent political system—ensuring that institutions such as the People’s Association and the Elections Department are fully independent, and civil society and critics are engaged not with suspicion but respect.

After decades of uninterrupted PAP rule, the most common argument against voting for a stronger opposition is that it could be destabilising—by leading to the loss of key ministers or undermining the strength of the Cabinet. But this is a false choice, built on a flawed assumption.

At this stage of Singapore’s political development, the PAP is overwhelmingly expected to form the government this coming election. It will continue to be supported by Singapore’s world-class civil service. President Tharman Shanmugaratnam’s personal stature adds a further layer of reassurance. So, the best time for change is now.

What’s more, a political system should never be so fragile that its strength hinges on the electoral survival of a few individuals. If good governance depends heavily on the re-election of select ministers, then it is the system—not the electorate—that needs strengthening. A stronger opposition does not diminish Singapore’s capacity; it expands it. It brings more voices, sharper scrutiny, and broader perspectives into our national conversation. That is not a risk. It is an opportunity.

What will change with a stronger opposition presence is that Parliament will better reflect the concerns of ordinary Singaporeans. A stronger opposition won’t make Singapore weaker—it will make Singapore more robust. It will ensure that policymaking is more responsive, more innovative, and more accountable. It will also help bridge the growing disconnect between existing government policies and the realities faced by ordinary Singaporeans.

This election, we have a choice. We can either endorse the status quo, accepting that the current system of overwhelming PAP dominance is sufficient to meet the challenges of a substantially changed landscape. Or we can vote for a stronger opposition, not as a protest, but as a necessary step towards ensuring that Singapore remains a world-class nation—not just in headline GDP figures, but in real-life affordability, financial security, retirement adequacy, quality of life, and a political system that is open and fair for all.

The best governments are not the ones that operate without challenge. They are the ones that are pushed to be better. Singapore deserves no less.

The writer, a senior counsel, is a member of the Workers’ Party.

Letters in response to this piece can be sent to sudhir@jom.media. All will be considered for publication on our “Letters to the editor” page.

If you enjoy Jom’s work, do get a paid subscription today to support independent journalism in Singapore.