The photographs circulating online of Yazan Kafarneh, a 10-year-old Palestinian boy on his deathbed in Rafah, southern Gaza, are meant to shock. Taken with his family’s permission, they show the “skeleton” his father said he’d turned into, of a human being seemingly without be-ing.

One can trace the outline of his skull, with his gaunt and jaundiced skin stretched tight over his forehead, collapsing below his cheekbones, and then taut again, almost on the verge of tearing, around his impossibly sharp jawline. His eye sockets are hollowed out, but it is there, in his irises looking upwards, and in his eyelashes bristling with apparent resistance, that one can feel his life energy, in its final moments, beaming towards us. What message is he trying to send?

It’s not only the tragic end of his life, but its entirety, that should confront our sensibilities about the ongoing horrors with Israel's war on Gaza. Before it began, Yazan’s cerebral palsy was increasingly under control, according to his family. He had access to physical therapy, medicines, and high-nutrient soft foods, including eggs and bananas. All of this allowed him to swim, even if he couldn’t walk. A photo of him prior to the war depicts a cherubic, smiling survivor of a God-given ill.

But he never stood a chance amidst man-made carnage. Once the war broke out, Yazan’s family didn’t have easy access to medications and specific foods. For the eggs, his parents substituted bread, made into a mush with tea; and for the bananas, other sweet foods. They moved Yazan and his three brothers four times in search of safety. They reached the Al-Awda hospital in Rafah on February 25th. Doctors and nurses administered antibiotics for Yazan’s pneumonia, but did not have a reinforced nutrition drink that he’d been having before the war. On March 4th, he died.

The photographs and videos we have of Yazan—cherub to skeleton—are at one level an excruciating insight into the suffering of the most vulnerable people there. At another, they are a visual depiction and timeline of global helplessness, if not intransigence, over the war, and of the futilities and failures to arrest the human catastrophe many saw coming. The UN says that 2.2m of Gaza’s 2.4m residents (over 90 percent) are now on the verge of famine.

Is what we’re witnessing really just a war, as grotesque as the question is, or something far worse? Just weeks into the conflict, scholars were already warning about the apparent genocidal intent of some Israeli leaders. In late January, the International Court of Justice (ICJ) delivered its first ruling in a genocide trial brought by South Africa. It did not call for a ceasefire—Hamas, designated as a terrorist organisation and not a state, is anyway beyond its ambit. It also did not make any declaration about genocide, a process that, problematically, could take years. But the ICJ did direct Israel, among other things, to “take all measures within its power” to prevent genocidal acts, to “prevent the destruction and ensure the preservation of evidence” related to genocide, and to “enable the provision of urgently needed basic services and humanitarian assistance” to Palestinians in Gaza.

Though the directives are binding, the ICJ has no power to enforce them. Recourse can be had through the UN Security Council, though it’s unlikely on this particular issue, partly due to the US’s support of Israel, if not complicity through arms sales. Nevertheless, because of the ICJ’s ruling, Israel’s allies find themselves in a “painful quandary”, Richard Gowan, an analyst at the International Crisis Group, told DW. “Israel and its friends will find [the ICJ ruling] hard to ignore.” In early February, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MFA) said that it was “studying the legal implications” of the ruling. It’s imperative that these allies keep pressuring Israel to abide by the ICJ’s directives. The Singapore government has a responsibility to do so, and in turn, every concerned Singaporean has a responsibility to pressure our government—we’re all implicated.

This moment demands of us, then, the base knowledge that democratic citizens need to participate in their polities. At the very least, in this instance, is an exploration of the history of genocide, the evidence from the current conflict, what genocide scholars have said, and a look at Singapore’s five-decade relationship with Israel—what connects you to an alleged, ongoing genocide. To leave such discussions to the elite chambers of our territorial nation-state system, one whose very constitution legitimises state violence against perceived enemies, would be a moral abdication, a willingness to look away, by consumers comfortably numb in relative material comfort. We each owe it to ourselves to find the right words to create space and meaning in our individual lives and communities, to accurately label “evil” when we see it.

More than that, we owe it to Yazan.

The word “genocide” is a combination of the Greek word γένος (genos, “race, people”) and the Latin suffix -caedo (“act of killing”). The former is part of words like genealogy and the latter words like infanticide. Raphael Lemkin, a Polish lawyer, coined the word in a 1944 book, Axis Rule in Occupied Europe, which examined Nazi policies. Lemkin’s criteria for establishing genocide would later influence the much-cited Article 2 of the UN’s 1948 Genocide Convention:

“… any of the following acts committed with intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnic, racial or religious group, as such:

(a) Killing members of the group;

(b) Causing serious bodily or mental harm to members of the group;

(c) Deliberately inflicting on the group conditions of life calculated to bring about its physical destruction in whole or in part;

(d) Imposing measures intended to prevent births within the group;

(e) Forcibly transferring children of the group to another group.”

Though genocide has occurred throughout history, it was only then that it became a crime under international law. Douglas Irvin-Erickson, a political scientist, has argued that even as late as 1959, many leaders “believed states had a right to commit genocide against people within their borders”, a damning indictment of the territorial nation-state system’s philosophical and humanitarian failings. Because of its origins, the word “genocide” has always been associated with Nazi pogroms against millions of Jews during the Holocaust. Notable retroactive applications include with the genocide of the Armenians by the Ottomans in 1915-16; and the genocide of the Herero and Nama peoples of present-day Namibia by the German Empire in 1904-08, considered the 20th century’s “first genocide”.

There have been numerous legal debates over the years pertaining to Article II. One is whether physical harm and killing is a necessary condition for genocide. No, as it turns out, which is why, for instance, the removal of children from indigenous groups in Australia and Canada has been classified as genocide, according to Omer Bartov, a professor of Holocaust and genocide studies at Brown University. Similarly, many use the term cultural genocide to describe the actions of China in Tibet and Xinjiang. Another debate is around which essential forms of identity are covered, and how they’re defined. For instance, in the Rwanda genocide in 1994, Hutu militias slaughtered up to 800,000 Tutsis (and others). Ethno-cultural similarities between the groups led the courts to argue that “if a victim was perceived by a perpetrator as belonging to a protected group”, then that would suffice.

Scholars and human rights lawyers regularly examine genocide and two other classes of crimes: war crimes, which are defined in the Geneva Conventions, and crimes against humanity, which are defined by the Rome Statute (and can occur outside battlefields). As early as October 15th, a week after Hamas’s savage attacks on Israel, Bartov, along with over 800 other scholars and practitioners, had been warning about the signs of genocidal intent amongst Israeli leaders. Bartov, who served in the Israeli Defence Forces during the 1973 war, grew more worried by November. “As a historian of genocide, I believe that there is no proof that genocide is currently taking place in Gaza, although it is very likely that war crimes, and even crimes against humanity, are happening,” he wrote in an editorial in The New York Times. “[F]unctionally and rhetorically we may be watching an ethnic cleansing operation that could quickly devolve into genocide, as has happened more than once in the past.”

Last month, his assessment got more dire: “[W]e are on the verge of either genocide, certainly extensive killing of civilians, extensive destruction... and ethnic cleansing.” And last week, Francesca Albanese, UN special rapporteur on human rights in the Palestinian territories, said that there are “reasonable grounds” to believe that Israel is committing genocide against Palestinians in Gaza, in a report titled “Anatomy of a Genocide”. To understand why, it’s worth first examining the genocidal statements that have bubbled around Israel over the past six months.

Immediately following the October 7th attacks, Benjamin Netanyahu, Israel’s prime minister, warned that the IDF would turn parts of Gaza “into rubble”, in keeping with the “huge price” Gazans had to pay for Hamas’s savagery. Not to be outdone, Yoav Gallant, Israel’s defense minister, declared two days later that, “We are fighting human animals and we are acting accordingly.” This dehumanisation of enemies, a prelude to many genocides, continued the next day. Major-General Ghassan Alian, the army’s coordinator of government activities in the territories, released a video statement lambasting Hamas for the attacks, but also Gaza’s residents for apparently celebrating them. “Human animals must be treated as such. There will be no electricity and no water [in Gaza], there will only be destruction. You wanted hell, you will get hell.”

The video occurred in tandem with a newspaper commentary, by retired Major-General, Giora Eiland: “The State of Israel has no choice but to turn Gaza into a place that is temporarily or permanently impossible to live in…creating a severe humanitarian crisis in Gaza is a necessary means to achieving the goal.” He wrote in another piece, chillingly, that “Gaza will become a place where no human being can exist.” Israel Katz, Israel’s energy minister, stoked the furnaces, rhetorical and logistical, on October 12th: “Humanitarian aid to Gaza? No electrical switch will be turned on, no water hydrant will be opened, and no fuel truck will enter until the Israeli abductees are returned home.”

At the end of October, long after the over 800 scholars had warned about genocidal intent, “Bibi” marshalled God. “You must remember what Amalek has done to you, says our Holy Bible. And we do remember.” Amalek is an ancient biblical nation depicted as out to destroy the Hebrews. In the book of Samuel, God issues a retaliatory order to King Saul: “Now go and smite Amalek, and utterly destroy all that they have, and spare them not; but slay both man and woman, infant and suckling, ox and sheep, camel and ass.”

Among other reasons this statement was notable is that in some multicultural societies, certainly Singapore, there is a tendency to associate bloodthirsty religious rhetoric only with Islam. After South Africa mentioned Amalek in its genocide case, Israel’s Prime Minister’s Office responded that the reference “was not an incitement to genocide of Palestinians, but a description of the utterly evil actions perpetrated by the genocidal terrorists of Hamas on October 7th and the need to confront them.”

As abominable as all these statements are, Israel’s right-wing leaders are relative softies compared to its right-wing media celebrities, as documented by Etan Nechin in “The far right infiltration of Israel’s media is blinding the public to the truth about Gaza”. Zvi Yehezkeli, analyst for Channel 13, said that 100,000 Palestinians should have been killed after October 7th. Yehuda Schlesinger, a correspondent for Israel Hayom, called for the “voluntary migration” of Palestinians so they wouldn’t raise “another Nazi generation”.

The most extreme discourse appears on Channel 14, founded in 2014, and which, along with Israel Hayom, is one of two channels, Nechin argued, that work symbiotically with Netanyahu’s right-wing agenda. Consider that Channel 14 publishes an online counter that records, among other things, the number of Palestinians killed in Gaza. They are all labelled “Terrorists we eliminated”. The infographic looks like the creation of a Zionist terrorist who’s just spent two weeks playing “Fortnite”, a survival video game.

Meanwhile, Shimon Riklin, a Channel 14 television host, “moderated” a talk show with this diatribe: “I am for the war crimes. I don’t care if I am criticised. I honestly don’t care. I am unable to sleep if I do not see houses being destroyed in Gaza. What do I say? More houses, more buildings. I want to see more of them destroyed. I want there to be nothing for them to return to.” Following his first statement, “I am for the war crimes”, two fellow panellists, a man and a woman, can be seen and heard chuckling along with him. The killing of innocent Palestinians, on Channel 14, is alternately gamified for one audience segment, and turned into comedy fodder for another.

How have these assorted proclamations filtered down to subordinates, ordinary citizens and foot soldiers? In November, Amichai Friedman, a captain and rabbi, told soldiers that “this land is ours, the whole land, including Gaza, including Lebanon.” (The IDF disavowed the statement.) More alarming was a video last December of Israeli soldiers dancing while singing a ditty inspired by their leaders’ quotes:

I’m coming to occupy Gaza

and beat Hezbollah.

I stick by one mitzvah

to wipe off the seed of Amalek

to wipe off the seed of Amalek.

I left home behind me,

won’t come back until victory.

We know our slogan:

there are no ‘uninvolved civilians.’

there are no ‘uninvolved civilians.’

“No uninvolved civilians” is another way of saying that no Palestinian—no man, no woman, no infant, no suckling—is innocent. That IDF soldiers might be chanting this now is a thought that makes one shudder. From Netanyahu to his corporals, religio-nationalist battle cries are ratcheted up as one goes down the chain of command, the further one is from the global public eye.

The impact of all this is clear. In the six months since the war on Gaza began, more than 30,000 Gazans have died, according to its health ministry. Over 22,000 are women and children. Hamas has said that it’s lost at least 6,000. (Israel puts the number at 13,000.) Over 75,000 have been wounded.

Between the single life of a Yazan and the overall body count—abstract in its enormity and cold in its reductiveness—lies another way to conceptualise the human suffering in Gaza: through specific groups. Just days ago, Israeli strikes hit a convoy including seven aid workers from World Central Kitchen, forcing it to suspend its operations that have delivered 43m meals to Gazans since October. (The IDF apologised for the “grave mistake”.) This brings the total number of aid workers killed in the war to at least 196, says the UN.

Meanwhile, one of the reasons we know what’s happening in Gaza is because of the brave Palestinian journalists. But Israel has been trying to stop them from reporting. It sometimes does so by killing them and their families, according to the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR). On December 14th, OHCHR said it had verified the killing of 50 journalists and media workers in Gaza. One example it cited was Mustafa Ayyash, the founder of the Gaza Now News Agency, who was killed on November 22nd, along with at least eight family members, in an apparent airstrike on his house in Al Nuseirat Camp. Prior to his death, Ayyash’s last post on X (formerly Twitter) was to report on a strike, also in Al Nuseirat Camp, that had killed his father, mother, sister, two brothers, and others.

The Committee to Protect Journalists has said that 77 journalists were killed in the war on Gaza last year while doing their jobs (72 Palestinians, three Lebanese and two Israelis). More journalists were killed there in three months, it said, than had ever been killed in any country over an entire year. To use a different lens, more journalists were killed in the first three months of Israel’s war on Gaza than were killed in the six-year second world war or the 20-year Vietnam war. It may seem premature to reflect on the war’s searing imagery, but the photographs of blood-soaked “PRESS” vests, taken by photographers who must wonder if they’re next, who must feel like they’ve seen through their lenses their future ghosts, are some of the most haunting.

Gazans have perished along with their homes and infrastructure. At least 56 percent of Gaza’s buildings have been damaged or destroyed and at least a third of agricultural land has been completely destroyed or burned out, according to geographers from the Decentralized Damage Mapping Group, who use satellite imagery to “improve the transparency, accountability, and equity in reporting and awareness of war’s effects on people and places.” The IDF has pummelled factories, power grids, water networks, and roads. “[E]very hospital in Gaza is either damaged, destroyed, or out of service due to lack of fuel; only 13 hospitals are even partially functioning,” wrote Annie Sparrow, associate professor at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, and Kenneth Roth, visiting professor at the Princeton School of Public and International Affairs, in February, in a Foreign Policy commentary titled “Destroying Gaza’s Health Care System Is a War Crime”. And according to the UN, over three-quarters of schools have been damaged or destroyed.

“When those who are occupied refuse to submit, when they continue to resist, we drop all pretence of our civilising mission and unleash, as in Gaza, an orgy of slaughter and destruction,” said Chris Hedges, an American journalist, in a recent speech. “...We expose the fundamental truth about Western civilisation: we are the most ruthless and efficient killers on the planet; this alone is why we dominate the wretched of the earth.”

From Jom’s vantage point, assessing limited evidence 8,000km away, Israel’s war on Gaza bears many of the signs of a genocide. Last week, we met the person here most closely connected to events on the ground, Dr Ang Swee Chai, an orthopaedic surgeon who left Singapore in the 1970s, founded Medical Aid for Palestinians, and has worked with Palestinians for over 40 years. Ang is a Christian who grew up subscribing to Israel’s perspective on the conflict before her experiences in Lebanon’s refugee camps in the 1980s exposed her to its tragedies. While she expressed to Jom her concern about anti-semitism, and said she’d never use the phrase “from the river to the sea” (which to some Jews means the erasure of their people), she was clear about the ongoing “genocide” in Gaza.

In a recent survey, over 50 percent of Americans aged 18-29 believe Israel is committing genocide, a far higher proportion than in older age groups, a sign of the generational shift in attitudes towards the conflict. It may be tempting to dismiss this usage as grandstanding, or the latest bout of hysteria in the propaganda war between Zionists and anti-Zionists, or an indication of the importance of shock value on social media. To be sure, there have been numerous instances of anti-Zionist excess since October 7th, including the post on October 10th by the Chicago Black Lives Matter organisation that celebrated the Hamas paragliders who slaughtered the Israelis. (It later deleted it.)

But to frame the use of “genocide” as posturing would be a mistake. We see its use by ordinary people as a deliberate moral and political act by the disenfranchised. Every time we see “genocide” we see less a legal definition than a call to action, less a calibration than a cry, less an appeal to our minds than our hearts. Its popular use today is, effectively, an assault by ordinary people on the dominant, hierarchical structures of our territorial nation-state system, the ones that dictate what we are allowed to say, and how we are allowed to behave. The great absurdity of “genocide” is that it’s most often deployed retrospectively, to tell us about the past. It’s laden with so much baggage, and requires so many sign-offs, that it’s almost useless in the present.

Amid the worrying rise of autocratic leaders in democracies around the world, an analogous debate is emerging around the use of the word “fascism”, particularly with regards to Donald Trump. Sceptics, like Jan-Werner Müller, a Princeton philosopher, have preferred terms like “far-right populism”. Yet just like with “genocide”, there is a risk that we may be sacrificing urgent action at the altar of presumed precision. “It would be foolish to start reflecting on fascism only when it is fully fledged,” said Müller, offering a counter-point to his own position.

Similarly, one day well in the future, we can expect genocide scholars, human rights lawyers, and the courts to finally decide if Gazans today are experiencing a genocide, war crimes, or crimes against humanity. (And if so, good luck trying to get the perpetrators out of Israel to stand trial.) But, even as we’re sensitive to the gravity around accusations of the so-called “crime of all crimes”, we must ask: are we simply tying ourselves up in definitional knots? What’s the purpose of the word “genocide” if it is powerless to prevent an alleged, ongoing genocide?

Perhaps we simply need a new word, one not so imbricated in the founding of the very nation now accused. Scholars, frustrated, are attempting to interrogate its limits. In “Genocide: when does state violence pass the threshold?”, Zoé Samudzi, a visiting assistant professor in Holocaust and Genocide Studies at Clark University, asked: “how can one prove intent or even decry the violences of genocide when the actor itself is a settler or colonial state whose very foundations constituted and necessitated racial dispossession, widespread theft, and collective punishment on native or other populations?”

So much about the longstanding morass in Israel and Palestine has always, ultimately, rested on power: the power to shape post-colonial policy and discourse, the power to control land ownership, the power to designate what is or isn’t a national identity, the power to legitimise some forms of violence but not others, and the power to attach labels like “terror” and “genocide” onto your enemies while absolving oneself.

When pro-Palestine activists and commentators are forced by television hosts to first condemn the October 7th attacks as terrorism before their voices can be heard—a moral litmus test upon which their acceptance rests—their worldview is being circumscribed by a hegemonic security discourse that privileges the actions of the nation-state. It sanitises retaliatory state violence, including when it leads to massive civilian deaths, even as it demonises the actions of non-state actors driven to violence by desperation. It does so by drawing a convenient line in the sand about the chronological origins of terror. In a cheeky attempt to usurp this hegemony, Cornel West, American philosopher, recently said on “Piers Morgan Uncensored” that Hamas is a “counter-terrorist group” that arose in the 1980s in response to the IDF’s much older “terrorism”.

To be clear, the desire to understand circumstance is not an apology for terror. Jom condemns the killing of any civilian. So do most Israelis and Palestinians, seemingly. Hamas’s popularity in Gaza has plummeted since October 7th, with a minority (38 percent) of Gazans keen for it to retain power after the war. Similarly, a minority (42 percent) of Israelis are supportive of Netanyahu’s continued onslaught. (Some 47 percent want a stop and a hostage deal.) Three-quarters of Israelis want Netanyahu to resign—half now, half after the war—while 88 percent of Palestinians want Mahmoud Abbas, head of the Palestinian Authority that governs the West Bank, to do so. If there is indeed a genocide occurring, it’s certainly not one with popular support.

Observing how carnage occurs without local support and in defiance of international pressure, it may be tempting for us in Singapore to throw our arms up in the air. But on the contrary, by tracing our relationship to Israel, we can better understand both our connections to its peoples, our obligations to them, and the power we have, both in the world of global diplomacy and through our economic linkages. For we are all beneficiaries of the same global, capitalist system. Samudzi described the fundamental contradictions of genocide, and human rights discourse generally, as “the de facto global hierarchy of humanity: the demarcations of certain people and lands as mere capital and labor for the benefit of others, capitalism’s calculus of the necessary destructions of lifeworlds—whether targets or so-called ‘collateral damage’—so that others may live and flourish.”

Not only, then, are we all forced to entertain the notion that a genocide is occurring now, but that the merchants of greed aren’t far behind. Like a pantomime villain with impeccable timing, Jared Kushner, in mid-February, told an audience at Harvard University that Gaza’s waterfront property could be “very valuable”. He suggested that Israel could move civilians to a safe area, possibly in the Negev desert, so that it could “go in and finish the job.” On whether Netanyahu may later prevent Palestinians from returning, he offered a pithy, “Maybe.”

Kushner is a real estate developer who served as Middle East adviser to his father-in-law, Donald Trump, during his time as president. And there’s a chance they may soon reprise their roles. If indeed global forces conspire to create in Gaza the conditions for “the Singapore of the Middle East”, as one Israeli politician had once suggested, what role exactly will we, the actual Singaporeans, play in all of this? A traditional, navel-gazing perspective on national interest would suggest that: as our Temasek-linked firms jostle for contracts to develop our old ally’s gleaming new waterfront, the likes of Yazan and other Gazans, dead or displaced, will be but a distant memory.

But there is another way.

All of us, particularly those in democratic societies allied to Israel, must therefore question the byzantine world of global diplomacy. A two-state solution is what many, including Singapore, ostensibly support. But decades of UN resolutions and apparent diplomatic pressure have come to naught. As our governments struggle to balance national interests, the concerns of their citizens, and apparent commitments to an international, rules-based order, are their public aspirations for a “two-state solution” more performative than genuine? Is “two-state solution” merely a lullaby sung by realists for idealists, as we all sleepwalk towards a one-state solution?

There is nothing novel about this for observers of Netanyahu’s decades-old rightward swing. It’s a strategy that has involved efforts to redefine Israel as the nation-state of the Jewish people, suffocate Gazans in what’s been called “the world’s largest open-air prison”, and sideline and weaken the more moderate Palestinian groups. In Enemies and Neighbours, journalist Ian Black cited Yossi Beilin, former Labor politician and architect of the failed Oslo accords: “When Netanyahu is up against those who are more hawkish, he will say, ‘It will not happen on my watch.’ When he speaks with those who are more moderate, he says, ‘I am ready to talk to the Palestinians, and I am committed to the idea of a two-state solution.’”

In late January, Netanyahu was interviewed by Douglas Murray, associate editor of the conservative magazine The Spectator, author of The Strange Death of Europe: Immigration, Identity, Islam, and a fiery advocate for Israeli aggression against Hamas. Netanyahu is sharp, polished, and persuasive in front of the camera, having long ago realised how to mobilise the media in his propaganda war. In ”The Netanyahu doctrine: how Israel’s longest-serving leader reshaped the country in his image”, Joshua Leifer called him “Israel’s first real TV prime minister. He took acting classes to perfect his public performances.”

In the interview, Murray asked Netanyahu about the diplomatic pickle Israel’s allies might now be in, given that many seemingly want the war to end. The latter depicted a civilisational battle between the “moderate axis of Israel and the moderate Arab states” on one side, and the “terror axis” of the three H’s: Houthis, Hezbollah, and Hamas on the other. “I think in America the great majority of people support Israel, they understand instinctively that Israel is fighting their battle…for them [radical Islamists] this is all one big battle of civilisation. Our civilisation against their wanton aggression, their violence, their rejection of all the values that we hold dear.”

It is one of Netanyahu’s many sleights-of-hand: suggesting first that the civilisational binary he adheres to has been foisted upon the world by radical Islamists; and then reducing their civilisation to a cavalcade of savagery. As part of the TV prime minister’s media arsenal, Netanyahu has weaponised Israeli victimhood to nuclear levels. Black wrote that when he “described demands to evacuate illegal West Bank settlements as supporting the ‘ethnic cleansing’ of Jews, Palestinians accused him of cynically appropriating ‘their’ narrative…”

Netanyahu also made a startling admission to Murray about the duplicity in global diplomacy. He claimed that all the foreign leaders he’s spoken with, “deep down in their hearts”, understand that Israel has to crush Hamas and that it has a just cause. But, he said, mimicking them, “we're having problems with public opinion so please help us out.” He pre-empted it with a cute escape clause. “All the [foreign] leaders that I talk to, you know what they say to me? I'll say not ‘All’ okay, ‘Nearly all’, okay, that allows everyone to be the exception if they don't want to admit what they actually said to me.”

In doing so, Netanyahu exposed the theatricality of global diplomacy. A recent ceasefire vote at the UN followed earlier resolutions that were vetoed by the US or China and Russia. Netanyahu has anyhow pledged to go it alone even without the imprimatur of his allies, so it appears, in any case, like all these UN formalities are, as he suggested, less about stopping the onslaught than appeasing a domestic base. In the case of Joe Biden, US president, it’s perhaps directed at the “uncommitted” movement among Democrats, which has undermined his already uncertain prospects for re-election later this year. The practice of global politics can seem feckless and opaque.

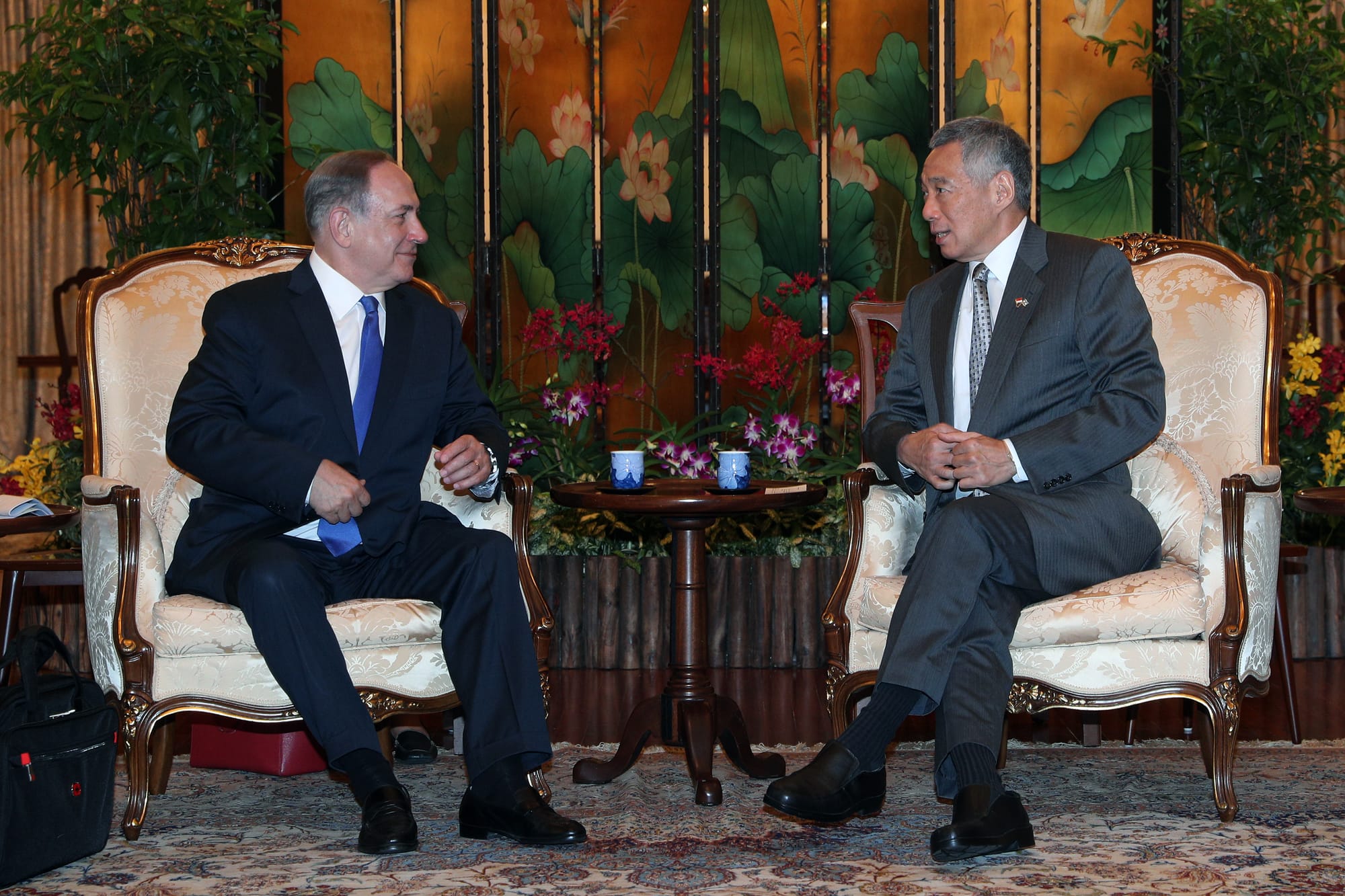

Are Singapore’s diplomats playing a similar game? Are they part of the cabal to have conveyed one message in private to Netanyahu and another in public to the UN and their citizens? MFA did not return a request for comment. What we do know is that since independence in 1965, Singapore’s leaders and national security hawks have depicted supposed parallels between Israel’s and Singapore’s geopolitical realities and existential threats. Singapore is like “Israel in a Malay-Muslim sea”, Lee Kuan Yew once quipped. (Unlike Israel, however, independent Singapore has not once experienced a smidgen of military aggression from our neighbouring states. Regional terrorist groups, by contrast, threaten all South-east Asian states.)

Israel and Singapore’s close political and military relationships have often been shrouded in secrecy, beginning with the labelling of early Israeli military advisors to Singapore as “Mexicans”, presumably to avoid complicating relations with Malaysia and Indonesia, who have still yet to formally recognise Israel. The sympathies that Muslim Singaporeans have towards the Palestinian cause has also likely factored in this calculus.

It’s clear that inter-state relations involve the theatricality of stage performances working in sync with back-room whispers and handshakes. We are regularly reminded of this, whether through fawning obituaries about the “statecraft” of Henry Kissinger, or dramatic challenges to this order, such as Wikileaks. The Singaporean “leak” of relevance is that in 2005, in a conversation with Hillary Clinton and other visiting American diplomats, Lee allegedly characterised Islam as a “venomous religion”. Though he later denied it, the statement, if true, would be in keeping with his historical suspicion of Muslims. This is partly what pushed him to welcome the Israelis on Christmas Eve, 1965, the unofficial start date for what writer Amnon Barzilai called “the great and continuing love story between Israel and Singapore, a love affair that was kept a deep, dark secret.”

With Israel and Singapore’s relations, the point is not so much about the theatricality, a definitional feature, but the fact that since the relationship’s genesis it has been performed at an elevated level. Wayang was, perhaps, our original sin. And because of this it’s fair for all citizens to be a little sceptical about anything that Israeli or Singaporean leaders say publicly about our countries’ ties.

So secure are the Israelis in our relationship that after October 7th, their embassy in Singapore started broadcasting incendiary propaganda through its Instagram channel. Separately, Eliyahu Vered Hazan, the Israeli ambassador, e-mailed members of Parliament (MPs) with gruesome details of the attacks, much to everybody’s disgust, according to two MPs from different parties who spoke to Jom. (The Israeli embassy and MFA did not return a request for comment.) Hazan’s media savviness was perhaps honed as a columnist at Israel Hayom, the aforementioned right-wing paper where he began his career, and also later as Netanyahu’s spokesperson.

Last week, the embassy’s attempt at historical revisionism on social media—comparing supposed mentions of Israel and Palestine in the Quran to negate the latter’s claims to statehood—received a rare public rebuke from the Singapore government, which led to the removal of the post. (Israel Hayom, incidentally, was founded and bankrolled by the late conservative American billionaire Sheldon Adelson, who was also behind Marina Bay Sands. It’s been described as “endless capital with a political agenda.”)

The vocal Singaporean backer of Israeli action is Bilahari Kausikan, a former diplomat who now heads the Middle East Institute at the National University of Singapore. He first defended Israel’s “war of annihilation against Hamas” on Facebook on October 10th. In mid-November, with the body count already past 11,000, including over 4,000 children, he published a problematic commentary in The Straits Times (ST), arguing that Israel’s actions in Gaza are justifiable as they are meant to “restore deterrence”. (It contained other scholarly gaps, which Jom highlighted.) Even though K Shanmugam, home affairs and law minister, then rebutted Kausikan politely, in early December ST allowed The Jerusalem Post to republish an excerpt with the headline “Israel-Hamas war: A view from Singapore on restoring deterrence - opinion”.

While Singapore officially cultivates a close friendship with Israel, it purports to do the same with the Palestinians. In Israel-Asia Relations in the Twenty-First Century, a book published last year, political analysts Kevjn Lim and Mattia Tomba cited sources close to the MFA who claimed that Singapore generally supports Palestinian resolutions at the UN “irrespective of what we may think of their merits, in order to give ourselves political cover to develop substantive relationships with Israel.” (MFA did not return a request for comment.)

If all this is true, it would simply add to the prevailing sense of helplessness amongst many ordinary Singaporeans. Unlike most other democracies, the government here has banned all public demonstrations, even peace rallies, that are in any way related to the war. Since October 7th, in other words, many Singaporeans have felt that our voices have been muted and our desires somewhat inconsequential to a tragedy that affects us deeply.

What can Singaporeans and others far from Gaza possibly do right now to stem the killing? Ironically, it could be in the words and beliefs of a chronicler of Nazi Germany where we find hope, purpose and restitution. Hannah Arendt was one of the 20th century’s most important philosophers, remembered best, perhaps, for describing “the banality of evil” in her portraiture of Adolf Eichmann, a key proponent of the final solution, at his trial in Jerusalem in 1961.

She was pilloried at the time because critics perceived her phrase to be downplaying the severity of the Holocaust. Yet in recent years her works, including The Origins of Totalitarianism, have enjoyed a resurgence, precisely because of the rise of right-wing (fascist?) forces around the world. Varied intellectuals have since attempted to more accurately reflect her view, including philosopher Judith Butler: “What had become banal—and astonishingly so—was the failure to think. Indeed, at one point the failure to think is precisely the name of the crime that Eichmann commits…for Arendt the consequence of non-thinking is genocidal, or certainly can be.” Arendt opposed the notion that subordinates in totalitarian structures, like Eichmann, can be exonerated because they were following orders. “No one has the right to obey,” she famously said. Not thinking while blindly following orders is something not only Hamas and IDF fighters may be prone to, but all of us, at various moments of our lives.

Lyndsey Stonebridge, a humanities and human rights professor, borrowed another signature Arendt quote for her recent biography’s optimistic title, We Are Free to Change the World: Hannah Arendt's Lessons in Love and Disobedience. And yet in a recent panel discussion, Stonebridge expressed caution about democratic life: “One of the things that’s really bad at the moment is that the spaces that we did have, could still have, for creativity, for resistance, for thinking, for solitude, education, culture, arts—have been taken down, are being taken down. That’s kind of where I’m losing hope. Because in order to have good politics, you need non-political spaces, to make sure they happen.”

It’s important, then, that we resist oppression, and create in Singapore the spaces for thinking, love, disobedience and action, spaces which have been sorely lacking since October 7th. With respect to Israel and Palestine, we need more transparency about our country’s relationship, official and unofficial, with Israel. We do not have to abide by the archaic geopolitical and security dogmas of the 1960s. Singaporeans must feel free to shape new policies of engagement with both Israelis and Palestinians, ones that honour our democratic society’s wishes, not the fever dreams of hawks still gripped by post-independence paranoia.

Does Singapore really believe that a two-state solution is achievable or do we just trade in diplomatic niceties at the UN? Why is Kausikan allowed a platform for his aggressive rhetoric, while ordinary Singaporeans are barred from peace rallies? Will disgraced Israeli politicians and military leaders later regard Singapore as a safe haven, as the likes of Zimbabwe’s Robert Mugabe have?

“Many Singaporeans want a bigger say in how our country engages with the rest of the world,” Faris Joraimi, Jom’s history editor, wrote on October 13th last year, at the start of Israel’s war on Gaza. “Consistency in our principles, after all, is increasingly at stake: should Singapore continue to stand by an entity that has repeatedly flouted the rules of the international system, which supposedly guarantees our security as well?”

Almost six months and over 30,000 bodies later, what each of us needs right now is the courage simply to think—and act.

This essay is from Jom's team. It is the first in a three-part series about Israel’s war on Gaza. “Merdeka, Palestine” by Iskandar Manis, is scheduled for April 12th and “Ang Swee Chai’s urgent message” by Sudhir Vadaketh, Jom’s editor-in-chief, is scheduled for April 19th.

We have put this first one outside the paywall. We trust that those who appreciate our journalism will get a paid subscription today. This is the only way we can continue to produce this work.

Letters in response to this piece can be sent to sudhir@jom.media. All will be considered for publication on our “Letters to the editor” page.