With the ruling People’s Action Party (PAP) holding 90-100 percent of elected seats in Parliament for 60 odd years, Singapore’s politics is unlike that of almost any other national electoral democracy.

It is often argued that such political dominance allows for more “long-termism” in policymaking. By this account, the government can take tough but unpopular measures—such as the Goods and Service Tax (GST) hikes, an openness to high rates of immigration and fiscal conservatism—that are supposedly in the long-term interest of the country, with less fear of electoral blowback. In contrast, intense political competition can lead to various shades of populism or “short-termism”, as rival parties struggle for votes, seeing no further than the next election.

This argument has been used in Singapore for decades to defend one-party dominance. It can be situated within a larger narrative about Singaporean exceptionalism: Singapore is “so uniquely vulnerable that it has limited policy and political options, that good governance demands a degree of political consensus that ordinary democratic arrangements cannot produce,” as Donald Low and Sudhir Vadaketh (Jom’s editor-in-chief) wrote. This kind of thinking has justified political “innovations”, such as the group representation constituency (GRC) system and the current approach to demarcating electoral boundaries, that may diminish the opposition’s ability to translate its share of the popular vote into elected seats.

One of the most recent and striking defences of this thesis came from Senior Minister Lee Hsien Loong in Sep 2024.“…in those [politically divided] countries, governments find that doing the right thing is not politically feasible, and then political leaders of all parties default to populism or short-termism to stay in power. Thankfully, Singapore has been an exception to this rule…As growth becomes harder to come by, as revenues becomes less buoyant, and as our politics become more fiercely contested, things can go wrong for us too. If electoral margins get slimmer, the government will have less political space to do the right things. It will become harder to disregard short-term considerations in decision-making. The political dynamics will become very different. Singaporeans must understand the dangers this creates, and so must the public service.”

Ahead of a crucial general election (GE), due by November 2025, it was a clear warning by the former prime minister, and son of the PAP’s co-founder, about the “dangers” associated with political diversity. But is this the case? Does one party’s dominance necessarily lead to long-termism that’s in society’s interest? This popular narrative deserves careful scrutiny. For instance, having one dominant party could lead to an insidious brand of paranoid politics, where that party increasingly resorts to harmful populism to “buy votes” while using its political dominance to increasingly obstruct its opponents, fearing even small opposition gains.

Moreover, at a time when economic and income growth are harder to come by, that dominant party may find it harder and harder to win popular support by delivering genuine economic benefits. It may then be tempted to increasingly use that dominance to resort to unsustainable, reckless financial populism and “dirty tricks” against opponents and critics.

This is precisely what happened in Mexico in the 20th century. Notwithstanding obvious differences between our countries, it’s worth examining the effects of one-party dominance there, as well as in Japan, my other case study, before contemplating the possible trajectories for today’s PAP. While it’s obviously in the PAP’s long-term interest to maintain its dominance, we shouldn’t assume, as Lee did in his speech to the public service, that it’s necessarily in Singapore’s.

Sign up for Jom’s weekly newsletter

Our newsletters combine weekly updates about Singapore with a “build-in-public” narrative, in which we tell readers about our start-up journey.

No spam. Unsubscribe anytime.

Few parties in any electoral democracy where elections are reasonably fair can match the PAP’s 65-year record of winning elections. One exception is the Institutional Revolutionary Party of Mexico, or PRI, which dominated Mexican politics for 71 years.

Mexico is an ancient country. Mesoamerican civilizations, such as the Maya and the Aztec, date back 1,300 years. In the 1520s, the Spanish conquered the Aztec Empire. In 1821, Mexico shrugged off the Spanish colonial yoke. But independence did not change much for ordinary Mexicans, as a land-owning elite dominated the young nation’s politics. As a reaction against that, the 1920 Mexican revolution established a modern state with democratic claims.

The PRI was formed in 1929 and quickly became the dominant political force. Under Lázaro Cárdenas, president from 1934 to 1940, the PRI government implemented ambitious economic and social reforms. Cárdenas also ensured that the PRI established a large patronage system that distributed benefits to various groups in exchange for political support. The government achieved great economic success in the mid 20th century through a policy of import substitution, the Soviet-inspired economic orthodoxy popular in the global South at the time. Mexico today is a middle-income country.

The PRI completely dominated Mexico’s legislature and politics for 71 years, losing some ground to a growing opposition movement only towards the end of the 20th century. During those 70 years, there were periods of reforming zeal, when PRI governments took tough actions to pursue long-term goals at the risk of short-term unpopularity. Perhaps those impulses were supported by the knowledge that they had a large electoral buffer to play with, giving them the latitude to spend political capital. For example, Cárdenas’s reforms in the 1930s included extensive land reform and the nationalisation of whole industries, acts which no doubt made him and the PRI many powerful enemies.

But during those 71 years, there were also periods when the PRI’s rule was all about pork-barrel politics and fixing opponents, to ensure that they lost as few legislative seats as possible–and preferably none at all. As the opposition grew in strength, the PRI increasingly fell back on outright electoral fraud, intimidation and uber “pork barrellism”. Finally, in 2000, the party lost the presidency.

So effective was the PRI’s febrile regime in maintaining electoral dominance that it elicited sharp comment from the revered Peruvian writer Mario Vargas Llosa in 1990: “I don’t believe that there has been in Latin America any case of a system of dictatorship which has so efficiently recruited the intellectual milieu, bribing it with great subtlety. The perfect dictatorship is not communism, nor the USSR, nor Fidel Castro; the perfect dictatorship is Mexico [under the PRI]. Because it is a camouflaged dictatorship.”

Towards the end of the 20th century, the PRI’s dominance was eroded in a gradual, piecemeal fashion. In the late 1970s, opposition parties gained a few seats in the lower house of the legislature. In 1988, the opposition won four of the 64 Senate seats, marking the first time the PRI lost a Senate seat (coincidentally a few years after JB Jeyaretnam’s victory in the 1981 Anson by-election ended the astonishing 100 percent monopoly PAP had enjoyed in the Singapore Parliament since 1966).

Also in 1988, the victory of the PRI candidate, Carlos Salinas, in the presidential election, was by a historically narrow margin. In 1989 the PRI lost its first gubernatorial election ever, in Baja California North. Several states elected non-PRI governors in the mid-late 1990s. In 1997 a non-PRI candidate became mayor of Mexico City. Finally, in 2000, the PRI candidate was defeated in the presidential election by Vicente Fox Quesada of the National Action Party, bringing the curtain down on the PRI’s 71-year dominance over Mexican politics.

So the beginning of the end for the PRI stretched over several decades, with small opposition wins harbingers of what was to come. Could this be the nightmare scenario that keeps dominant parties, including the PAP, up at night? It goes without saying that I am not making a direct comparison between Singapore’s PAP and Mexico’s PRI in the 20th century. For instance, in Singapore, electoral fraud, such as ballot stuffing, would be impossible without the collusion of the opposition party—whose observers can have eyes on ballot boxes continuously, from the polling station to the truck to the counting centre, up till vote counts are released.

However, there are parallels in the political dynamics when one compares the long rule of the PAP and the PRI. In both cases, hyper-dominance in the legislature and a strong governmental influence over most of society’s institutions did not always and in every regard coincide with “long-termist” politics. For the PRI, it often coincided with economic populism, pork barrel politics and opposition-fixing.

Japan’s Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) offers another rare example of one party dominating electoral politics for a long time. In this case, the dominance has stretched from 1955, with only two brief periods when the LDP was out of power (1993-94 and 2009-2012).

Japan began to democratise during the Meiji Emperor’s reign, between 1868 to 1912. Under his successor, elections and a modern party system started taking shape, though the electoral franchise was still limited. Following the Great Depression of 1929, conservative, militaristic forces came to dominate politics, a development that ended with Japan’s defeat in the second world war.

After a brief period of extreme political polarisation in the 1950s, the current contours of Japan’s politics came into view from the 1960s. In this electoral landscape, the LDP dominates an electoral system that holds free and fair elections. Japan has a viable and vibrant opposition, one which won a majority of seats in the lower house in the 2024 elections. The country’s legislature has many parties, including the Japan Communist Party as well as right-of-centre parties committed to a stronger geo-political role for Japan in the world. This could partly be due to Japan’s electoral system embodying a hybrid of the British “first past the post” system and proportional representation.

Japan’s case, on the face of it, does not lend support to the thesis that electoral dominance by one party is necessarily associated with “long-termism” in policy-making. There have been bursts of reforming zeal by LDP governments. But there have also been periods of lacklustre governance and outcomes, often leading to the swift exit of a prime minister, details of which are beyond the scope of this essay. Having said that, the comparison between Japan and Singapore is imperfect partly because the LDP is far less dominant than the PAP.

Even before the latest election where the LDP lost its majority, the opposition in Japan controlled 37 percent of seats in the lower House of Representatives (a figure Singapore’s opposition would rejoice over). Moreover, the LDP has lost power on two occasions in Japan’s post-war history, while the PAP has won every election since 1959, the first after Singapore attained internal self-government. Lastly, Japan has strong institutions, such as the Bank of Japan and Japan’s press, that operate relatively independently of the executive.

Let’s come back to Singapore. Is there evidence that the PAP’s political dominance has been a necessary condition of long-termist policy-making, or that the one has enabled or led to the other? One bit of counter-evidence comes up from the get-go: the flood of good long-termist policy-making that happened amidst intense political competition from the late 1950s to the mid 1960s, when the government of the day had a far smaller share of parliamentary seats than it has now—or, in others words, when there was a much stronger opposition in Parliament than there is now.

In “The New Normal is the Old Normal: Lessons from Singapore’s History of Dissent”, historian PJ Thum argued:

“Between 1955 (Singapore’s first election for partial self-government) and 1963 (Singapore’s independence from Britain)...came the widely admired policies which underpinned Singapore’s prosperity for the next 40 years: housing, education, social security, and infrastructure. The Central Provident Fund (CPF) was created in 1955; David Marshall introduced Meet-the-People sessions in 1955; a flexible and open trilingual system of education came out of an All-Party Report on Education in 1956…the Housing Development Board (HDB) succeeded the Singapore Improvement Trust in 1959; the Winsemius survey which led to Singapore’s industrialisation was done in 1960; the Economic Development Board followed in 1961.”

Conversely, the PAP government in the modern era, where it dominates Parliament, has also, at times, taken measures that could be deemed to be populist. The term populist here refers to measures that could be seen to be directed more at electoral advantage rather than the pursuit of a well-defined policy aim consistent with accepted governance best practices and expressed government policy thrusts. Populism here means policies that would be widely seen to be more about good politics than good policy.

Recall that shortly before the 2011 election, Mah Bow Tan, then minister for national development and the archetypal PAP civil service/scholar leader, said in reply to a journalist’s question about the extent to which policy was dictated by electoral considerations: “everything has got to do with elections.”

Consider a few recent examples of what could be seen as populism. In September 2017, Khaw Boon Wan, then transport minister, acknowledged that the construction of the Bukit Panjang light rail transit (LRT) station was done under “political pressure”, seemingly implying that political considerations had nudged the relevant agencies to adopt rushed measures that cut corners from the standpoint of long-term engineering systems performance. A subsequent parliamentary exchange in 2017 did not shed much new light on Khaw’s reference to “political pressure.” Whatever Khaw meant by this reference, these pressures were felt at a time when the PAP held well over 90 percent of parliamentary seats. Shouldn’t one party’s dominance ease those pressures and ensure “long-termist” decision-making?

Meanwhile, the government’s spending on the People’s Association (PA) rose from $389m in 2010-11 to $1,178m in 2023-24. The PA is a powerful statutory board under the Ministry of Culture, Community and Youth (MCCY). It organises events and activities that promote government policies, such as raising awareness of safe distancing measures and vaccination programmes during the Covid-19 pandemic. The government has repeatedly stressed the PA’s critical role in acting as a bridge between it and the people, a reason also given for why opposition MPs cannot be grassroots advisors to the PA—a point of contention. Even if not by design then, as the MCCY has stated, PA events effectively often provide a platform for PAP MPs and defeated PAP candidates to engage constituents.

The social utility of various PA programmes is not in doubt. But the dramatic scale of the PA budget increase since 2010 raises questions about its urgency—all the more when set against the severe fiscal pressures created by higher healthcare expenditure as society ages, itself cited as a key reason for (painfully) raising the GST in an inflationary era. The issue of the PA’s burgeoning budget has been raised in Parliament, for example by Leong Mun Wai, a non-constituency member of Parliament (NCMP) with the Progress Singapore Party (PSP), in 2021. No doubt there are many reasons that could explain this—such as the programs run by the PA to address our aging society as well as to further social mobility. In Parliament in 2016, in reply to Sylvia Lim, an MP with the Workers’ Party, Chan Chun Sing, minister and also then deputy chairman of the PA, explained that the PA had to cater to an “increasingly sophisticated population”. But an expanded PA footprint coincides with an expanded budget for activities that are widely seen as building political capital for PAP MPs and defeated PAP candidates.

Indeed, in a recent interview, Inderjit Singh, a former PAP MP, implied that, in his view, the party controls the PA partly for perceived electoral gain. “Whether being in control of PA is going to help us win more votes or less, I think this is something that may change over time,” Inderjit said. “But I think in the PAP, the belief probably still is that that’s an important avenue to reach out to residents and therefore, you know, opportunity for their potential candidates to get support.”

Separately, during the Covid-19 pandemic, the government announced that NDP fun-packs would be made available to almost every single household in Singapore, including the well-off. In 2020, I raised a question in Parliament about this, given my concern about whether this was a necessary use of public funds at a time of great public need during the pandemic. The reply from the government was, in effect, that this exercise was about raising the collective morale amidst despondency. But how then can we differentiate between populist measures and necessary, morale-raising, solidarity-building ones? Any good populist would defend her stance as necessary for national solidarity and morale-raising.

In recent years, the government has resorted more visibly to providing cash grants that are not means-tested, alongside those (e.g. the Silver Support Scheme) that are. For example, CDC vouchers and Budget 2024 National Service LifeSG Credits are provided to all Singaporeans, including the very rich. However, the policy impulse behind such moves could seem at odds with the general stance of the government, which is to extend assistance in a targeted manner to those who need help.

Those who walk the ground in private estates, as I did, know that those living in private homes sometimes feel left out of government grant schemes such as Service and Conservancy Charges (S&CC) rebates. This may leave their votes “swingeable.” After GE2020, Lawrence Wong, then minister for national development (and current prime minister), said that there had been a fall in PAP votes among those living in private properties.

This is not to say that the government implements universal grant schemes to sway better-off voters. It could be argued that fostering national solidarity requires such schemes, to show equal recognition for all, including the middle-class and rich. And to be fair, there are a small number of Singaporeans living in private homes who are cash-poor and living from hand to mouth. But it is surely interesting that such taxpayer-funded spending is sometimes directed towards better-off Singaporeans in a broad brush stroke manner rather than in a targeted fashion—actions that may, intentionally or not, have an effect in swinging votes in private estates. After all, as Joe Biden once said, “Don’t tell me what you value, show me your budget, and I’ll tell you what you value.”

Another way to interrogate the supposed connection between one-party dominance and long-termism is to examine the situation in other countries. In electoral democracies which return slim margins of victory for the ruling party and with regular alternation of power between parties, one might expect longer-term decisions such as infrastructure-building to be blocked, with funds shunted towards populist measures to “buy votes” for the next electoral cycle. Is this the case world-wide?

Not really. In December 2022, Tsai Ing-wen, Taiwan’s president, extended the term of compulsory National Service (NS) to one year, basically tripling the length of NS. All three presidential candidates supported this NS extension. This decision would clearly qualify as a tough, long-termist and potentially very unpopular measure. Shouldn’t they all have competed with one another to call for shorter NS, so as to gain electoral advantage?

In the US, where the Democratic and Republican parties are as divided as they’ve been for a long time, the CHIPS and Science Act passed with strong bipartisan support in 2022. This law set aside US$280bn (S$386bn) to help build the domestic semiconductor industry, and to pursue longer-term goals of an economic and geopolitical nature. Shouldn’t this money have gone to cheques to buy over voters instead?

The Anthony Albanese government in Australia has put in motion plans to finally build a high-speed rail to connect the major cities on its east coast, promising “generations of opportunities”. The first phase is estimated to cost A$61-108bn (S$53-94bn). Shouldn’t this money have been used to bribe voters instead?

In 2014-2020, the European Union (EU) allocated €220.8b (roughly S$331.2bn) to fight climate change, despite numerous other countries failing to meet their Paris climate accord targets. Presumably this money could have also gone to populist measures.

Why is it that when governments in other democracies govern with razor thin majorities or via fragile coalitions and face the very real prospect of the opposition winning power, the political system does not always break down, with all priorities subsumed under the government’s over-riding need to divert funds to “buy votes?”

It could be that in these other democracies, there are institutional bulwarks that constrain the ability of ruling parties to adopt country-destroying variants of populism. These include: the so-called Fourth Estate—the media, the commentariat and Key Opinion Leaders—that can call out harmful populism and cause reckless populists to lose votes; the courts, which for instance have struck down governmental actions as being inconsistent with climate change commitments; civil society organisations (CSOs), which can call out behaviour by political actors that is more populist than right; and independent central bankers, who may use monetary policy tools to limit the harm caused by reckless fiscal populists in power.

For a democracy to generate good outcomes, it is a necessary but not sufficient condition to have non-fraudulent elections, as we have in Singapore. It is also necessary to have these other institutions that inject the meaningful matter into the empty mould of fair elections, to harden into a real democracy that works. While the issue is complex, it is far too simplistic to say that big majorities by one dominant party make for, or are even needed for, long-termism in policy-making. If that were the case, no infrastructure would get built and no unpopular measures taken in countries like South Korea and Taiwan, for example. And the PRI in Mexico would have been steadfastly long-termist throughout the 20th century.

Taking a step back, I want to pose but not answer a question: is an obsession with long-termism even necessarily a good thing, in an era when change happens fast and quick adaptations need to be made to black swan events and sudden economic and geopolitical shifts? No doubt some long-term decisions need to be made—large infrastructure building, for example. But could an excessive focus on long-termism crowd out the country’s capacity to change and adapt quickly at the level of both policy principles, executive strategies and tactics? Will the most “long-termist” country necessarily succeed in the 21st century?

I will conclude with some more speculative thoughts. This question, concerning the relationship between political dominance and long-termism, should not be looked at irrespective of economic conditions. In times when the economic pie is growing and governments are flush with tax revenues, an electorally dominant government with authoritarian tendencies can afford to implement tough long-term policies while at the same time spending monies to placate voters. Let’s call this benign soft authoritarianism.

But in times like the present, when the low hanging economic fruits have all been plucked, when GDP growth of 2 percent is celebrated, productivity growth is sluggish and disruptive technologies and geo-politics are creating dark economic clouds, a very different picture emerges. It is now hard for governments to be long-termist and “buy off” voters at the same time.

In such times, a benign soft authoritarian regime may take a very different and ugly turn, as the PRI appears to have done towards the end of its dominance—with pork barrel spending, intimidation of the opposition and other measures to stack the electoral deck all going into over-drive. Difficult times can turn benign soft authoritarians into toxic, hard ones—ramping up the anti-opposition, pork-barrelling and rules-rigging fervour.

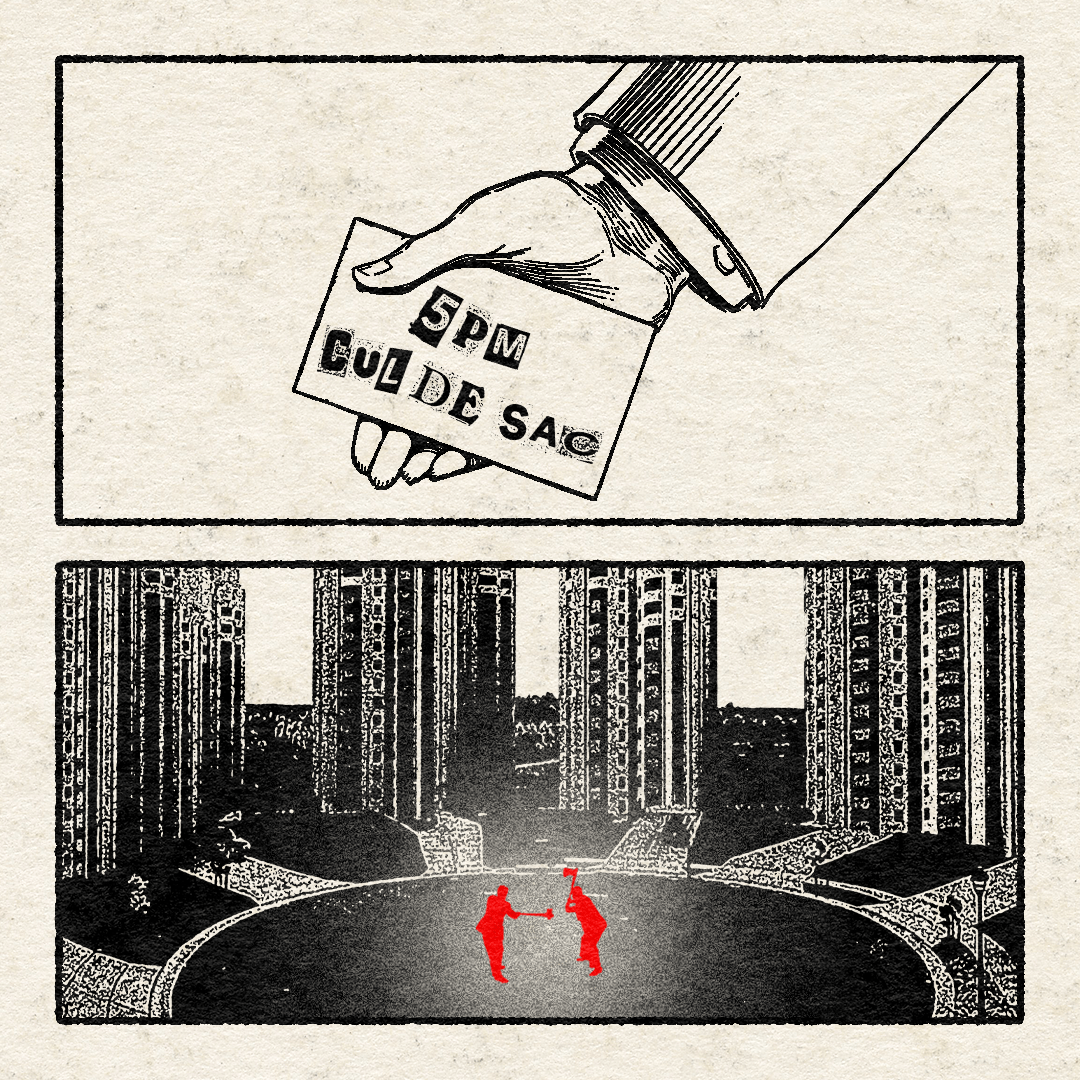

And for anyone disinclined to realise how quickly a soft authoritarian regime can turn hard, consider this quote from the late Lee Kuan Yew: “If you are a troublemaker…it’s our job to politically destroy you. Put it this way. As long as JB Jeyaretnam stands for what he stands for—a thoroughly destructive force—we will knock him. Everybody knows that in my bag I have a hatchet, and a very sharp one. You take me on, I take my hatchet, we meet in the cul-de-sac.”

If one looks at statements from current PAP leaders, a fear can be discerned that even small opposition gains could herald the thin end of the wedge and the end of the PAP’s rule; and hence must be resisted at all costs. For example, this is what Lee Hsien Loong, then prime minister, said at a rally during the GE2006 campaign, about what would happen if Parliament had more opposition MPs—at the time he said this, there were only two fully elected opposition MPs out of roughly 80. (He later apologised for this remark.):

“Then, instead of spending my time thinking of what is the right policy for Singapore, I’m going to spend all my time—I have to spend all my time—thinking what is the right way to fix them, what is the right way to buy my own supporters over, how can I solve this week’s problem and forget about next year’s challenges?”

Recent statements by Wong also suggest an alarmist view about any opposition gains. “Please don’t think it is guaranteed that the PAP will win and form a stable government,” he told party members at its recent conference. (Never mind that the party still holds over 90 percent of elected seats.) All this points to the PAP’s long-standing worries about political diversity. Yes, a very competitive democracy can perhaps descend into irrational polarisation and toxic gridlock if the balancing effect of strong independent institutions and politically literate and invested voters is absent.

But there is a “Goldilocks zone”—a competitive democratic system with a capable and responsible opposition; but one with the ballast of strong, independent institutions and politically literate and invested voters to guard against populism, excessive short-termism and self-serving authoritarianism.

In Why Nations Fail: The Origins of Power, Prosperity, and Poverty, academics Daron Acemoglu and James Robinson, who (with one other colleague) won the Nobel prize in Economics in 2024, argued for the importance of “institutions that provide broad-based opportunities and incentives for people to invest, innovate and engage in productivity-enhancing activities...these can only survive in the long haul if they are supported by inclusive political institutions that prevent the monopolization of political power by a small segment of society while also enabling the state to enforce laws.” This sounds good, doesn’t it? How do we get there?

It could be argued that the PAP can retain its dominance and institute political reforms to strengthen independent institutions; support a strong civil society and independent media; and enhance electoral fairness. This would bring Singapore closer to Acemoglu and Robinson’s Goldilocks zone of democratic and dynamic yet stable politics.

Will they?

Absolutely no agenda for political or electoral reform, to address bugbears like the role of the PA and the definition of electoral boundaries, was contained in Wong’s signature Forward Singapore report. An appetite for serious political reform among PAP backbenchers cannot be discerned. I cannot recall any PAP MP having mooted parliamentary interventions such as the PSP’s full motion on Electoral Boundary Review Committee reform, for example.

Let’s imagine what the world looks like from the standpoint of a sincere reformer within the PAP—like a Mikhail Gorbachev, someone who wants to reform the one party dominant system in order to save it. Would she push for reforms that could possibly end that one party dominance, as Gorbachev did? Or would it be more convenient to continue calibrating policies that place just enough pressure on the opposition and execute just enough populist measures to maintain that one party dominance while preserving some semblance of financial sustainability and also not provoking a huge public backlash about political unfairness that could bring the opposition to power?

But as economic growth becomes harder and harder to achieve, will this hypothetical game of clever calibration become more and more like a game of musical chairs where no one knows when the music will stop? And when it does, could that usher in an era of political instability, where the dominant party ramps up unsustainable short-termist policy-making and opposition-fixing, as the PRI did towards the end of its long spell of one party dominance?

Those patriots who want Singapore to find that Goldilocks zone of a more balanced, stable politics with strong institutional and cultural ballast should not hold their breath for internal PAP reformers. Instead, they should encourage voters to support the growth of a responsible Opposition and bring about better political balance through the only means possible—at the ballot box.

As suggested by Tony Tan, then president, in his address to Parliament in 2016, when I first became an NCMP:“…we must have a political system that enables a government to govern effectively and in the interest of all. We often see countries suffering from deep divisions in their societies and crippled by political gridlock. Our system discourages narrow interest-based politics and encourages clear electoral outcomes. This has served us well…Our political system has delivered stability and progress for Singapore. But this system must be refreshed from time to time, as our circumstances change.”

The voters play the most important role in any democracy. It’s up to them to decide if it’s time for the system to be refreshed.

Leon Perera served with the Singapore Economic Development Board before co-founding an Asia-Pacific market research consultancy in the year 2000, where he is currently chairman of the board and executive director at the company that acquired it. For 30 years, Leon served with various civil society organisations and charities, in various capacities. He joined the Worker’s Party and served as an NCMP in 2015-2020 and as an MP in 2020-2023. In July 2023, Leon resigned from the Workers’ Party on pain of expulsion. He currently contributes to the work of various political, civil society and independent media organisations. This essay is written purely in his personal capacity.

Letters in response to this piece can be sent to sudhir@jom.media. All will be considered for publication on our “Letters to the editor” page.

If you enjoy Jom’s work, do get a paid subscription today to support independent journalism in Singapore.