Last week, Tay Kheng Soon, architect and author, was the guest at a Jom Cakap event. The octogenarian Tay, a planning and urban development pioneer who’s worked alongside every government since independence, narrated many stories about his conflicts and dealings with “Kuan Yew” over the years.

One audience comment gave him pause. Even though Lee was a strong personality, he was always apparently willing to “sit down and talk to people who had a different view”; but today’s government is not, this person argued, for it allegedly often uses POFMA to label as lies what’s actually just “another point of view”. What did Tay think about the contrast between these two approaches to dialogue?

“It’s such a complicated issue, I don’t know where to start,” Tay began, for once without a quick-fire response. He then said that we are living through a transitional moment, which are characteristically “confusing” and “internally contradicting”. He was referring to the handover of power from the so-called 3G (third generation) of leaders in the ruling People’s Action Party (PAP) to the 4G, led by Lawrence Wong, prime minister. “In any kind of political system there is always the good cop and the bad cop. I think Lawrence Wong is trying very hard to be a good cop. But if he is to succeed, I think he needs a bad cop who is a bit more subtle.”

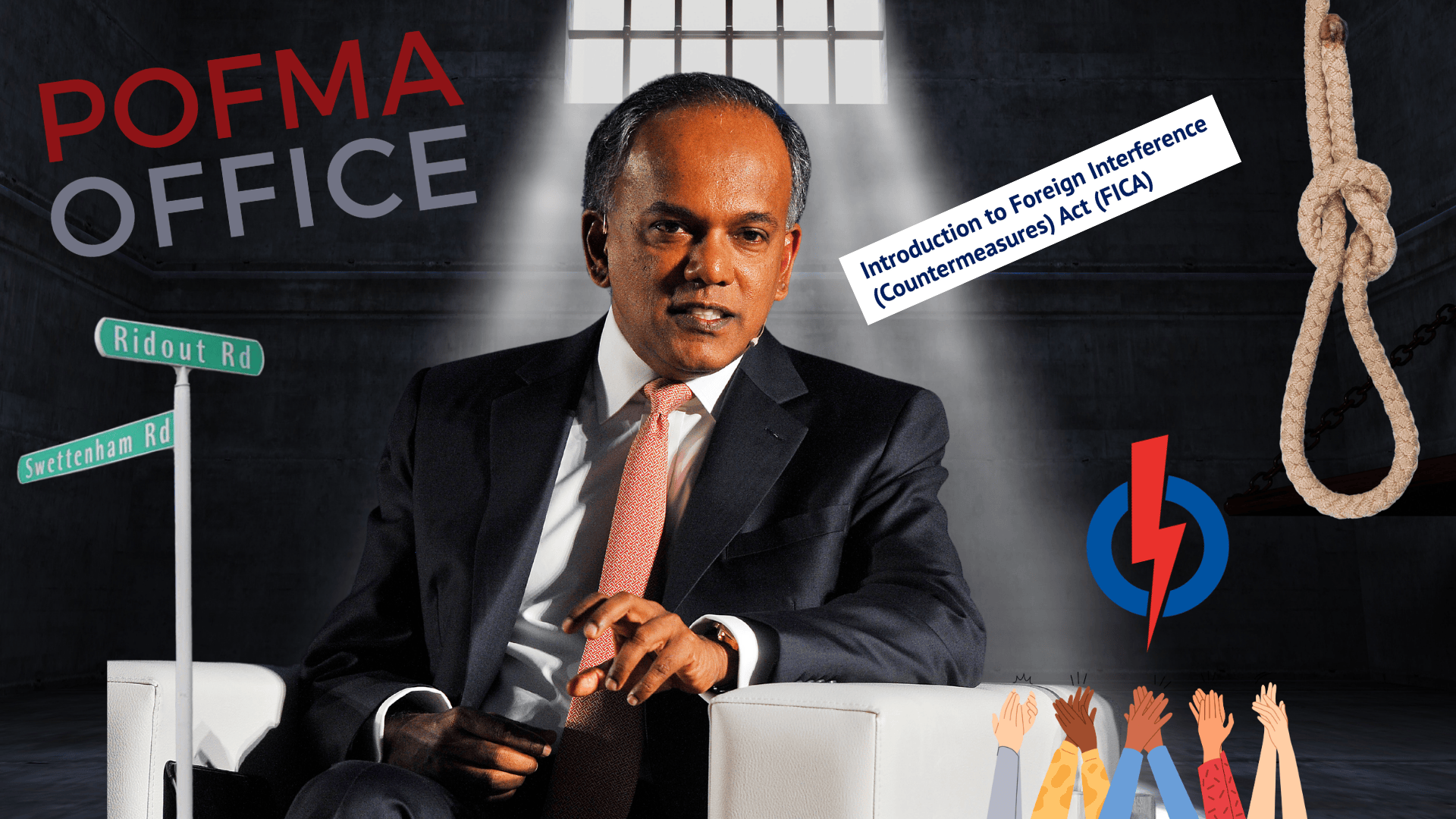

Tay had articulated one of the central dilemmas with Wong’s leadership team. Is K Shanmugam, the powerful law and home affairs minister, an asset or a liability to the 4G?

Sign up for Jom’s weekly newsletter

Our newsletters combine weekly updates about Singapore with a “build-in-public” narrative, in which we tell readers about our start-up journey.

No spam. Unsubscribe anytime.

For most of Singapore’s post-independence history, Lee Kuan Yew, our leader, was also our “muscle”. He could strong-arm communists during negotiations in secluded rooms, wax lyrical on international television while denouncing CIA interference in our fledgling state, and growl about striking unionists in crowded town squares, moving effortlessly between the varied theatres of perpetual battle he perceived. He boasted about carrying a “very sharp” hatchet for his enemies, preferring to be feared than loved by his own people. “Machiavelli was right. If nobody is afraid of me, I’m meaningless.”

Yet as Lee aged and slowly slunk into the background, his doting apostles anointing him with the inventive title of “minister mentor”, he also, perhaps inevitably, mellowed. At some point early in the prime-ministership (2004-24) of his son, Lee Hsien Loong, the spirit of the fiery, rabble-rousing, nationalist street-fighter was reincarnated in the body of Shanmugam, then a member of Parliament. The roles of leader and muscle split, creating a more familiar good cop-bad cop dynamic within the ruling elite.

As the younger Lee beamed across goofy videos on social media, much of the public-facing “dirty work” was left to Shanmugam, who’s appeared to relish it more with time. He rose swiftly, first becoming minister for law in 2008 and then also minister for home affairs in 2015. This dual role means that he oversees everybody from the Attorney-General’s Chambers (AGC) to the Internal Security Department and the Singapore Police Force (SPF). Shanmugam helps create laws (as an MP); Shanmugam helps implement laws (as law minister) and Shanmugam helps enforce laws (as home affairs minister). Clearly, he’s able to effortlessly rise above conflicts of interest that might hobble lesser mortals. Lee Hsien Loong once told the courts that in the deliberation over 38 Oxley Road, Shanmugam was effectively able to hold three separate views on demolition in accordance with three separate roles: friend to the Lees, cabinet member, and an individual.

Shanmugam’s the architect of a battery of new laws, including POFMA and FICA, many of which have concentrated even more power in the executive—further entrenching the notion of “lawfare” pioneered by the elder Lee. “Shan” has assumed the mantle of swashbuckling warrior, for whom there are threats everywhere that must be pummelled into submission, whether foreign ones such as Richard Branson and The Economist; or local ones such as academic Donald Low or the young women activists who wanted to discuss POFMA at his meet-the-people session. Almost every suspected political machination from today’s PAP, whether the countless POFMA orders handed to critics or the meticulously released revelations in 2023 about extra-marital affairs involving four politicians, is assumed, fairly or unfairly, to be the handiwork of Shanmugam. So much so that one wonders if “Blame Shan” is the convenient deflection for any undignified party action. In Jom’s voter sentiment survey, respondents ranked the younger Lee as Singapore’s most popular politician, liked across party lines; and Shanmugam as our most polarising, liked by those aligned to the PAP, but not by the rest. Good cop, bad cop.

The suspicion about Shanmugam has been intensified by revelations that he’s been renting from the government a palatial colonial bungalow on Ridout Road, which sits on a property of about 250,000 sq ft, larger than three football fields, or equivalent to about 250 average public housing flats; and that he also recently sold another bungalow on Astrid Hill for S$88m, or almost 150 times the value of a median resale flat. Though all these transactions are legal—but of course—the optics are terrible, in a society where many are struggling amidst the spiralling cost of living. The bad cop has not just accumulated power during his reign, but immense wealth too (through his property dealings).

There is a related concern about class empathy. Does the “Rajah of Ridout” today have more in common with ordinary Singaporeans or global plutocrats? When he cracks down on activists and journalists, is he more protecting the interests of ordinary people or the elite? To be sure, it’s an issue also facing Wong and our other multi-millionaire leaders. Just because one comes from humble beginnings does not make one humble; just because one struggled financially 50 years ago does not make one understand today’s financial struggles. The survivorship bias of Singapore’s “rags-to-riches” politicians seems to often blind them to contemporary social mobility challenges.

When Wong selected his first cabinet last year, analysts were, among other things, looking out for two low-probability scenarios. Shanmugam bulls wondered if he might get picked as deputy prime minister; bears wondered if he might lose one or both of his portfolios. In the end, there was no change. Worryingly, Wong also kept Lee Hsien Loong and Teo Chee Hean on as senior ministers, meaning that the same arch-conservative triumvirate still exercises considerable power over the party and society.

Theories abound. One is that Wong, who was not unanimously selected by his peers, is still reliant on their patronage. Another is that he is looking for a way to gently ease Shanmugam out of the fold, and replace him with a more agreeable “bad cop”, perhaps Edwin Tong, also a senior counsel and current minister for culture, community and youth. (Tong’s sparring with Pritam Singh, leader of the opposition, during the latter’s Committee of Privileges hearing, appeared like an audition.) An alternative theory is that Wong quite likes having this bad cop around to take the heat, enabling him to maintain his smiling, chirpy, guitar-man demeanour, to gloss over the party’s hegemonic control. Whatever the case, the inescapable fact is that the three are indeed part of Wong’s chosen cabinet. This undermines some of his other imperatives, like the “renewal” in the ranks he claims is necessary, or his supposed desire to nurture a more consultative government. The lingering presence of Lee, Shanmugam and Teo, in other words, suggests that it’s very much business as usual at the PAP.

Yet it’s also too simplistic to suggest that Shanmugam’s oppression is as bad (or worse) than the elder Lee’s. There are many signs of Singapore’s liberalisation over the decades, including the fact the dreaded Internal Security Act has not been used on political opponents in recent times. The notion that the elder Lee was willing to sit down and countenance alternative views while today’s government shuts them down through POFMA must also be contextualised. For one, the elder Lee did not have to contend with today’s informational universe—falsehoods could not proliferate at the pace they do now. The overall media sector, if one includes independent channels like Jom, is far freer and less crippled by self-censorship today than before.

Shanmugam, meanwhile, is also actually known as somebody who’s happy to have candid conversations in private, whether with queer activists or Palestinian sympathisers. Unlike those in the 4G, he arguably has the requisite political capital and latitude to shape public opinion on more polarising issues, such as queer rights. Yet it’s also undeniable, as evidenced in the long journey towards repealing S377A, that his theory of social change is the classic, hierarchical PAP one, which prizes backroom dealings between ageing patriarchs over open discourse. The rush by “Malay community leaders” to condemn the two young women activists, based on Shanmugam’s single-perspective video and before they’d listened to the women, effectively racialised an issue that had nothing to do with race. These leaders’ subsequent reluctance to harshly criticise PAP firebrand Calvin Cheng for far more provocative comments—suggesting to exile almost 1,000 Palestinian sympathisers here—only confirmed their adherence to the bad cop’s model of societal management.

Separately, there are others outside the PAP who believe in Shanmugam’s value to the cabinet. An opposition politician told Jom that Shanmugam is one of the most “hardworking” and “brightest” people in the country. “If I were putting a cabinet together, I would want someone like that to be in my cabinet. No question about it. Because there's a mean nasty world out there, and you need someone who is able to deal effectively without emotion with the kinds of threats that are out there.” Yet they were also circumspect about Shanmugam’s counter-threat orientation, stressing that they’d want him to be outward rather than inward facing, because with the latter “he might perhaps see skeletons that don't exist.”

Therein lies the dilemma. We each desire certain elements of the bad cop but not others. Ultimately, Shanmugam might be judged within the party by that most democratic of indicators: the performance of his Nee Soon team at the upcoming election. At GE2020, against a relatively light-weight team from the Progress Singapore Party, Shanmugam and comrades scored 61.9 percent, a middling score only slightly better than the party’s overall vote share, and well below its top performers. Any significant drop could imperil his position, hastening his departure from the cabinet. At some level, it’ll also serve as a barometer for the kind of leader and society Singaporeans want.

“To swing the big hatchet may be out of tune with the new requirements,” Tay had told us at last week’s event. “I wouldn’t be surprised if the bad cop will be changed because it’s out of sync.” Despite having joked about “Kuan Yew” and scores of his lieutenants, Tay had still not actually named today’s bad cop. We sought clarification. “I don’t want to name names lah,” he responded, before breaking off into his trademark guttural laugh.

All of us joined in, though humour gave way to a somewhat despondent silence, about the fear that still hung in the air, that somebody up there might be listening, in 21st century “global city” Singapore.

Good cop, bad cop, haiyah. Feels like we’re still in the same interrogation room.

Sudhir Vadaketh is Jom’s editor-in-chief. If you enjoy Jom’s work, do get a paid subscription today to support independent journalism in Singapore. If you’re keen to watch the session, Tay Kheng Soon had asked a friend to film it and publish it online.

Letters in response to this piece can be sent to sudhir@jom.media. All will be considered for publication on our “Letters to the editor” page.