Content warning: This story mentions self-harm. If you need support, a list of resources is available at the end of this essay.

April 7th 2020—the start of Singapore’s circuit breaker, a nation-wide, partial lockdown, to contain the outbreak of Covid-19.

As an introvert, I welcomed the isolation. It afforded me time to reflect on life, and to assess how I was coping with work and my personal relationships.

I am not usually given to nostalgia. But as I pondered about the state of my well-being, I kept returning to a memory of me sitting on the floor of my room at boarding school, in England.

The year is 1991, I am 17. I am bathed in a crimson glow (I was really into red bulbs). Prince’s “Diamonds and Pearls” is blasting in the background, drowning out the laughter and chatter along the corridor outside. I am holding a knife, its blunt tip on the edge of my wrist. I push down and drag it back and forth several times. I don’t want to die. I only want to watch myself bleed; to feel the dull wince of being alive.

Even now, I still can’t find the words to adequately describe how I felt. Perhaps a messy, convoluted mix of ennui, loneliness, anguish, despair; fragile emotional states seeking nourishment from a cavernous, insatiable pit at the bottom of my stomach. Something I tried to feed with late-adolescent desire, distraction, and despondency—in short, music, make-up, male approval, Martini & Rossi.

By then, I had already lived five years as a full-boarder, which meant I didn’t have to leave the school on weekends. I had prided myself on being a conscientious student—I took my role as a stereotypically studious Asian seriously.

But without warning, I lost interest in my academic pursuits and my grades suffered. A creeping restlessness settled below the surface of my skin. My sense of purpose evaporated, eviscerating an already shaky self-identity. It left me yearning for meaning but, in my naivety and immaturity, I resorted to quick, superficial fixes. I come from a middle-class family and want for nothing. What was wrong with me? I kept asking.

The stoic, English reserve I had absorbed over the years stopped me from sharing what I was going through emotionally and psychologically—with friends, family and staff. I don’t remember any offer of counsel either. Our teachers and housemistress seldom, if ever, asked about our well-being. Even if we wanted help, where would we look? The only connection computers had at that time was to the power supply. No one breathed a word about mental health. Besides, we didn’t have the vocabulary to give structure and coherence to our thoughts and emotions. You were expected to outlive these teenage ‘growing pains’. If not, you ended up suicidal, or with an eating disorder, which affected some of my peers.

During the circuit breaker, it dawned on me that it was as a teenager that I first started to suppress any feelings of inadequacy and existential dread. I began to bury them, believing that they were ugly and socially unacceptable. It was my way to continue to function in a world that seemed hostile to frailty and dysfunction.

That is, until it was no longer tenable. Last year, three decades after I dragged a knife over my wrist, I decided to seek professional help on a regular basis. And that’s when I was diagnosed with a mental illness.

The idea of mental health is not a 21st century construct. For millennia, scientists, physicians, and lay people have formulated theories—supernatural, somatogenic and psychogenic—about the causes of mental disorders. Some experts have argued that it's not a precise science; but dependent on a combination of risk factors, particularly the role of ‘nature’ (genes) versus ‘nurture’ (environment) in the development of mental illness, a debate that ignited in the late 19th century. Despite the breadth of research in this area, some cultures continue to blame demonic possession or religious punishment. In Asia, societies misguidedly judge mental illness as a sign of weakness, a lack of self-discipline, a character flaw or a form of attention-seeking behaviour. Because they are a source of shame for many, mental disorders have often been trivialised and disregarded.

Historian Loh Kah Seng argues that as a former colony, the nation-state had not only “received Western psychiatric expertise” but also “suffered from the inner contradictions and failings of colonial rule.” Singapore is an international port city, a “transnational space” where external influences shape attitudes toward mental illness. In other words, Singapore’s relationship with mental illness is a product not only of European concepts of mental disease, but also the customary practices of migrants from China, India, and South-east Asia. Despite their different origins and beliefs, the various ethnic groups shared the same idea that mental illness was “governed by cosmological or spiritual forces.”

Mental illness was primarily seen as a problem of law and order in the early days of colonisation, limiting the state’s initial response, says Loh. Police would pluck off the streets those thought to be mentally sick and throw them in jail. This practice eventually stopped after the murder of an inmate. In 1841, the British built the Insane Hospital, which “marked the beginnings of specialised care” for those with mental disorders. It was renamed the Lunatic Asylum in 1861.

Singapore’s mental asylums functioned as “social laboratories for transforming patients into ideal subjects,” says Loh. These institutions brought care and treatment “from the community to the state”, and were, as Loh notes, used to control ethnic groups, particularly the Chinese, who the British found to be “unruly” and “obstructive”. Patients were already being stigmatised then, notably by psychiatrist William Ellis, a medical superintendent of the Lunatic Asylum, who called them “irrational and dangerous”.

With the reform of psychiatric regimes in Britain in the early 20th century, language improved. In 1927, Singapore renamed the Lunatic Asylum the ‘Mental Hospital’, and the following year moved it to a larger space. When the 1935 Mental Disorders and Treatment Ordinance replaced the 1863 Lunatic Asylum Ordinance, the term “person of unsound mind” replaced “lunatic” or “insane”. For the first time, doctors were given the power to admit patients, and voluntary treatment was allowed. In 1951, the Mental Hospital was again given a new name, Woodbridge Hospital, which eventually became the Institute of Mental Health (IMH) in 1993. It remains the only government psychiatric hospital.

Over those decades, Singapore’s mental health legislation evolved to better manage asylums and other public services. The Mental Disorders and Treatment Act 1965—modelled on the UK Mental Health Act 1959—became the only law that governed involuntary admission through legal means. It was superseded by the Mental Health (Care and Treatment) Act 2008, which commenced in 2010 and gives the State the power to detain persons with or suspected of having poor mental health conditions, and who might be dangerous to self or others. (The merits of this power are still debated.) Once a medical practitioner examines them, the arrested individual could then be admitted involuntarily into a psychiatric institution for up to 72 hours initially. Have we returned full circle to the days of law and order?

I remember Woodbridge Hospital—named after a bridge over a nearby stream—being synonymous with a place where “siao”, “gila” (Hokkien and Malay for “crazy”, respectively), or “cuckoo” patients would be interned. Adults frequently warned, “If you don’t behave, we’ll send you to Woodbridge,” in order to scare children into submission. These negative connotations would sometimes be accompanied with the gesture of an index finger drawing clockwise circles in the air next to one’s temple. Persistent stigma and discriminatory attitudes towards people with mental health problems proved that it was going to take much more than a name change to shift deeply rooted mindsets.

Having studied in England from age 12 in the mid-80s, and then returning to Singapore for my tertiary education in the early-90s, my formative, pubescent years unfolded at a time when mental illness was mostly relegated to the confines of hospitals and mental institutions.

Things have changed radically since.

Mental health has never been more widely and openly discussed than it is today, from news coverage to plot points in TV dramas, movies, theatre and literature; to the expository focus of documentaries, the discursive, intimate lure of podcasts, and the confessional nature of social media. But while we might be more attuned to the state of our own mental well-being, and increasingly comfortable talking about it, we’re still far from eliminating the stigma and discrimination around mental illness. In an IMH study published in 2017, some 46.2 percent of Singaporean youth surveyed said that they would be “very embarrassed” if they were diagnosed with a condition. While 44.5 percent of all respondents associated negative and pejorative words with mental illness, such as “crazy”, “weird”, and “dangerous”. Another 25.5 percent said that those with mental health conditions were “pitiful”, “sad”, and “need love or care”. Let’s not equate feeling pity and sadness to being compassionate and understanding. Rather, it often comes across as condescension.

That said, empathy has likely grown because of the impact of the pandemic. Lockdowns and social isolation caused a steep decline in our well-being. The World Health Organization (WHO) reported that global prevalence of anxiety and depression increased 25 percent during Covid. Last year, an online Covid-19 survey in Singapore found that 76 percent of respondents felt sad or depressed, while 65 percent were lonely. A collective grief—brought on by the loss of routine, structure, connection and loved ones—not only exacerbated existing mental health issues, but also triggered new incidences of it. In 2020, Singapore saw a record of 452 suicides, the highest count since 2012. (The number fell to 378 in 2021, perhaps because people found more avenues to get help.)

WHO says that the pandemic has been “a wake-up call for all countries to step up mental health services and support.” More importantly, Covid-19 has revealed cracks in our healthcare system—like the existing inequalities of living conditions and access to services for certain marginalised and vulnerable groups.

The global health crisis has also shattered the silence that shrouds persons living with a mental illness. Many have hitherto resisted treatment. The Singapore Mental Health Study (2016-2018) found that less than a quarter of Singaporeans seek help after being diagnosed with a mental illness. It can take up to 11 years for someone to get treatment. One of the main reasons is stigma. Another is, as was my case, a misguided notion of self-reliance, compounded by the consistent call to be “resilient”.

But now, given the widespread stressors of the pandemic, it has become “okay not to be okay”. It is no longer imperative to present an image of perfectionism. One psychiatrist has called the pandemic an “equaliser”, what mental health needed to “stop being stigmatised and start being valued.” In Singapore, the number of calls to a suicide hotline for those aged between 10 and 19 years saw a 127 percent jump from 2020 to 2021.

Until last year, I was fervently opposed to therapy; I was worried that I would end up blaming my mental health issues on my childhood, parents and family. That would be too easy, I thought. I was adamant to stay fully accountable for the person I became: suck it up and deal with it, so I persisted. But the pandemic disrupted the rhythm of apathy and antipathy that I spent a lifetime rehearsing, forcing me to sit and confront my issues without the noise of the quotidian jostling for my attention. I realised how exhausted I was of being ‘me’. I finally relented, allowing myself to embark on a path of self-discovery. Still, exposing myself to a clinical psychologist did not prepare me for the ultimate unearthing.

I was diagnosed with borderline personality disorder (BPD) towards the end of last year. It was shocking at first, but, honestly, as the fact sank in, not so much. In trying to understand what this meant for me now and for my future, I started to make sense of my past—why I had behaved in ways that were out of character and contradictory to the person I thought I was. Some of my BPD-related issues: a pattern of instability and mistrust in interpersonal relationships—characterised by a fractured belief system that expected nothing in my life to be secure and reliable; a poor self-image and weak sense of self—viewing myself as unworthy and inadequate; a nagging fear of abandonment; and chronic feelings of emptiness and self-loathing. Growing up, these afflictions were often intense and overwhelming. I inhibited a mind and body that were in a constant state of flux, though not to the point that I couldn’t function in school or social situations, for which I’m thankful. Over time, through the practice of mindfulness and perhaps a mellowing with age, these symptoms have abated.

Until the diagnosis, the only times I had heard about BPD was when, as a journalist, I interviewed people who had survived one or more suicide attempts. Listening to them talk about their challenges made me feel seen—fully understanding how important it was for people with mental illness to talk about what they experience.

One of them, who was diagnosed with BPD, lamented the difficulty in finding a psychologist willing to accept them as a client. Discrimination and misconceptions exist, even within the medical profession. Borderline personality disorder is one of the most misunderstood mental illnesses; persons with BPD are often labelled as “demanding”, “difficult”, and “treatment-resistant”.

A second interviewee, who has schizophrenia, half-jokingly told me that when they volunteered on a helpline, the most troublesome calls were from people with BPD. Yes, the stigma is real.

My journey towards recovery has been fraught but revelatory. Through talk therapy, I’ve come to accept that while BPD has shaped me, it doesn’t have to limit me. In taking ownership of my illness, I’m also choosing to reclaim my identity unashamedly; to find dignity in the face of living with BPD. This knowledge has empowered me to find ways to heal, as well as to start to value and accept myself. Medication has also reduced my anxiety and regulated my moods, which has stabilised the foundation on which I take these baby steps, contributing significantly to the treatment process.

The next stage of accepting the diagnosis was deciding what to do with the information. Whom should I tell? How would they react? Would my friends shun me, my parents brush it off as normal teenage angst? And what about my colleagues?

Always allow yourself to be pleasantly surprised: my friends have been curious, accepting, and non-judgemental; my parents, less vocal, but supportive nonetheless. Regrettably, many people with mental illness who have revealed their conditions have been censured, chastened or ostracised. Worse still, if they have to contend with family members repudiating them.

Mental health disclosure at the workplace is another point of contention for many adults already employed, or looking for a job. What’s the right thing to do? And who is this ‘right thing’ by; you or your colleagues? Technically, prospective employers should not ask applicants to declare personal information about their mental health, unless there is a job-related requirement—as stated in updated guidelines by the Tripartite Alliance for Fair and Progressive Practices.

So, it’s a bit of a conundrum. On the one hand, I didn’t want to seem like I was hiding useful information that could affect Jom and my co-workers. But on the other hand, I don’t want to be limited by the BPD either, or to have to deal with latent unconscious bias. The worst thing that could happen would be for any undesirable behaviour to be attributed to the disorder—no one wants to be pitied or to lose self-autonomy.

The reaction from Jom’s editor-in-chief, Sudhir Vadaketh has been reassuring. A few days after I shared the news, he called to ask me what the “done thing”, or protocol, was as an employee, and how it might affect my performance. A small panic descended: was this what it was like to feel wary about being stigmatised? He clarified that what he wanted to know was whether it was beneficial for the employee with a diagnosed mental disorder to disclose it to their colleagues. “It might create more empathy,” he explained. How kind, I thought.

There are also practical considerations to disclosing my condition on a public platform.

Would my current health insurance plan be nullified? After all, it’s not uncommon for insurers to penalise existing customers, or deny life insurance and other kinds of coverage to potential clients if they develop a mental illness. Is it any wonder that people choose to conceal their diagnoses, like some ghastly, forbidden secret. As it is, current options in Singapore are very limited for private health insurance that covers mental health issues, even if they don’t impact one’s physical health. At least half of these plans are targeted at employers, rather than individuals. Perhaps, the government could include a provision in the upcoming anti-discrimination legislation that prevents companies from rejecting an applicant with a mental illness?

And lastly, the court of public opinion—like the sword of Damocles hanging over my head: how would I deal with negative feedback and unconstructive criticism?

It’s a risk, let’s not deny that. And I’m taking it.

Tsen-Waye Tay is Jom’s head of content. She will be leading Jom’s editorial efforts in the mental health space. In a future piece she will share a “wishlist” for Singapore—how society can improve its approach to mental illness.

This essay is one of several that Jom has published free to coincide with Singapore’s 57th National Day.

If you enjoy Jom’s work, do get a paid subscription today to support independent journalism in Singapore.

If you or someone you know has a mental illness or concerns about their mental health, is struggling emotionally or feeling socially isolated, there are ways to get immediate, professional help, especially in a crisis. Use the following list of resources to find the advice and support you need.

Helplines

- Community Health Assessment Team: +65 6493-6500/1 and www.chat.mentalhealth.sg

- Institute of Mental Health's Helpline: +65 6389-2222 (24 hours)

- National Care Hotline: 1800-202-6868 (8am - 12am)

- Samaritans of Singapore: 1800-221-4444 (24 hours) /1-767 (24 hours)

- Silver Ribbon Singapore: +65 6386-1928

- Singapore Association for Mental Health: 1800-283-7019

- Tinkle Friend: 1800-274-4788 and www.tinklefriend.sg

Counselling

- Care Corner Counselling Centre: 1800-353-5800

- TOUCH Care Line (for seniors, caregivers): +65 6804-6555

- TOUCHline (Counselling): 1800-377-2252

Online resources

- Fei Yue's Online Counselling Service

- Mindline.sg

- My Mental Health

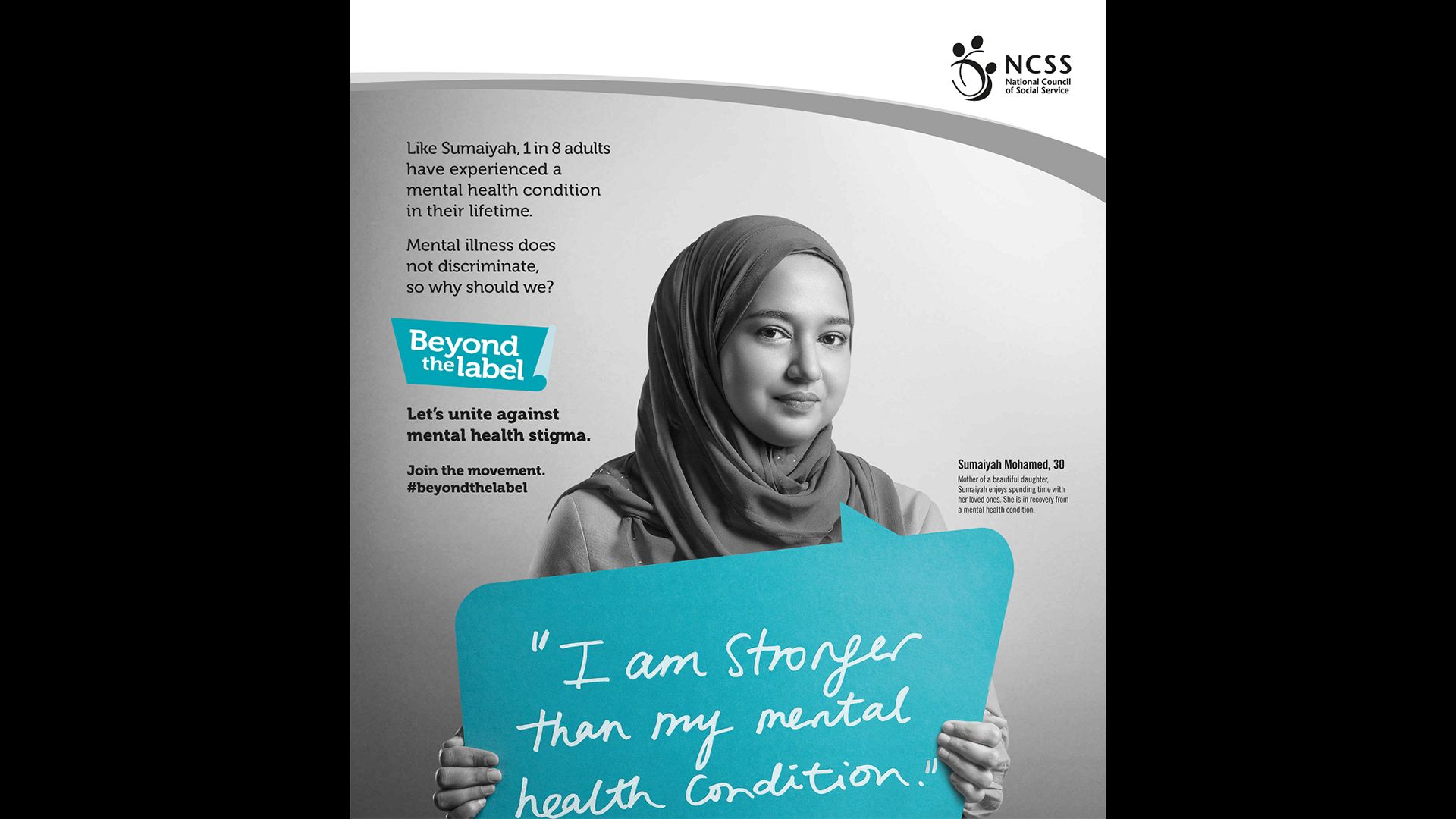

- National Council of Social Service Mental Health Resource Directory