In 1960, the Singaporean Malay public intellectual Harun Aminurrashid travelled to Jerusalem. It was a stop on his journey through Arab countries after a pilgrimage to Mecca. He wrote about his experiences in Meninjau ka-Negara Sham (Viewing the Levant). In Jerusalem, past and present forged tangled paths. Narrow lanes, mules, and antique houses transported Harun to “a society of olden days, untouched by the influence of this atomic age.”

However, anti-colonial struggles for freedom in the Third World crept into conversations with locals. When Harun mentioned Singapore’s proximity to Indonesia, the imam of Al-Aqsa Mosque praised Sukarno for fostering Afro-Asian solidarity. At Harun’s hotel, a waitress asked why he carries a British passport. Harun explained that his government only controlled internal affairs then, but “before long, Singapore will most certainly become a free nation.” Negara merdeka. In the dying rays of a colonial sunset, Harun’s imperial passport let him move through an increasingly bordered world. His optimism belied the bitter quarrels to come over merger, Malaysia and race, over which Palestine also loomed.

All around him, people seemed to be heading farther away from sovereignty and freedom. The waitress, a Christian Palestinian, took Harun to a rooftop and pointed at the town of her birth, annexed by Israel, to which she could not return. Harun’s Palestinian driver, Herrand, narrated what he and others he knew experienced during the 1948 Nakba, the mass expulsion and dispossession of Palestinians. His trembling voice often went silent, and grief was written on his face, said Harun. Jordan’s troops patrolled the West Bank, areas it controlled until Israel captured them in the Six-Day War of 1967. UN flags marked its buffer zone with Israel, a “No Man’s Land”. Palestine was, and remained, a fractured landscape.

August, 1982. A young Chinese Singaporean doctor named Ang Swee Chai responded to an international SOS call to treat war victims in Lebanon. She had seen the terror unleashed in Beirut by Israel on television in London, where she lived with her husband, the exiled left-wing human rights lawyer Francis Khoo. What she saw contradicted the Israel she was brought up to believe in. Ang was raised in a conservative church that told its congregants to support Israel. Arabs were terrorists and descended from the Philistines, while the Israelis were direct descendants of the biblical Israelites. Her Christian friends believed—as many in evangelical churches today still do—that the gathering of the world’s Jews, into a single ethnic state called “Israel”, fulfilled biblical prophecy.

“Doctor, are you going to Lebanon to help my people?” said a Palestinian professor to Ang, as she recalled in From Beirut to Jerusalem. He was from Jaffa, he said, where the famous Jaffa oranges first grew. His people became refugees, but “Palestine” was a real place. “Doctor, you must see Palestine.”

She was not entirely convinced, but in the Beirut camps of Sabra and Shatila where Palestinian refugees lived, Ang met “people who were warm and generous and who kept telling me of a home their young had never seen. Of a place called Palestine they were forced to flee in 1948. And their determination to return one day.” They taught her Palestinian history, songs, dances, and the patterns they wove on cloth. She tasted za’atar and Arabic coffee for the first time in a bombed-out home.

Late last year, as public anger grew over Israel’s murderous siege of Gaza, Singapore’s Ministry of Home Affairs warned against “importing foreign politics” and letting “external events” affect our precious racial and religious harmony. But Singaporeans can’t seem to turn away. Why does that “conflict” enlarge beyond its local dimensions? Why do our leaders have to keep trying hard to contain and manage our response? As Harun’s and Ang’s experiences show, Singaporeans’ long-held ideas about Palestine uphold myths that maintain the status quo in our part of the world too.

In their encounters with Palestine, both our travellers were proven wrong. Harun knew it was a historical space shared by all three Abrahamic traditions, but was nonetheless struck by the peaceful Muslim-Christian relations he saw, which predated the state of Israel and thrived in spite of it. While a Muslim pilgrim, the sites he visited—associated with Rachel, Jacob, Abraham and the Virgin Mary—occupied less bounded identities, being revered by all Palestinians. Harun was puzzled that locals of both faiths say “alhamdulillah” (praise be to God) and “in sha’ Allah” (if God wills it).

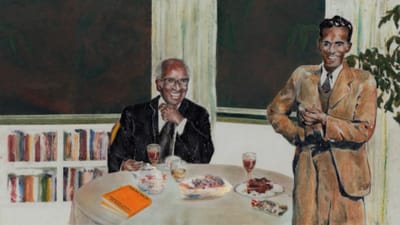

Ang, meanwhile, held convictions about Israel’s special place in religious narratives, where a biblical past provided a framework to explain modern territorial claims. No matter how much that past was being imposed on the present, however, to drive it in a particular direction, the present refused. Ang reckoned with the reality in front of her. In September, a month after she arrived, Israeli-backed Lebanese militias murdered perhaps as many as 3,000 Palestinians over two days and nights, in what’s known as the Sabra-Shatila Massacre. Ang was there, treating a relentless stream of the injured and dying, surrounded by screaming and gunfire outside the hospital walls. Ordinary people did not despair, however, inspiring Ang to become an outspoken advocate of Palestinian liberation. While Ang painted this as a dramatic transformation, it also feels rooted in her existing commitment to humanitarian justice. She founded the British NGO, Medical Aid for Palestinians in 1984.

Palestine blurred the lines and boxes both Harun and Ang were conditioned to see, especially religious ones. Object, text and practice have long connected Singaporeans to Palestine as a sacred geography and past. Generations were raised to know the Hebrew prophets, with Bethlehem and Nazareth on their lips. As a child I was regaled about the Night Journey of Muhammad, who travelled from Mecca to Al-Aqsa Mosque in Jerusalem, then up into Heaven and back. Along the way he meets all the prophets before him before speaking to God, with Palestine at the centre of this movement across time and dimensions of existence.

But which level of time and space do we attend to? Many lament the burden of millennia here, over which people manipulated by stories have been fighting over hallowed soil. Our ministers now say that it’s not our place to interfere in an ancient struggle between “Semitic tribes”. Yet the refrain that there is “too much history and too many prophets” in Palestine is often invoked to dismiss the urgency of the present. Scholars point out the centuries of peaceful co-existence in historic Palestine between Muslims, Christians and Jews, who all enjoyed status and security under Ottoman rule. The stranger is Zionism, which alongside events unfolding now, have far more recent origins.

As a modern political movement, Zionism attempts to identify all Jews with its aims of creating a mono-ethnic state. Its founders, including the Hungarian-Jewish journalist Theodor Herzl, were honest about the colonial plan that was needed to ensure its success, as he wrote in a plea for help to the notorious British imperialist Cecil Rhodes: “How then do I turn to you, since this is an out-of-the-way matter for you? How indeed? Because it is something colonial…” In 1895, Herzl wrote in his diary of the need to “spirit the penniless population across the border”, thus making Palestine’s ethnic cleansing central to the Zionist project.

The myth of an ancient conflict also holds that the state of Israel fulfils an “indigenous” right of Jewish return after a long time of exile. While the “Promised Land” has doubtless been meaningful to Jews for centuries, the idea that they are entitled to their own state in Palestine was a 19th-century invention. Zionism’s disdain for Palestine’s local population as inferior or non-existent, its narrative of a divine mandate, and objectives of territorial conquest and demographic replacement share much with modern European colonialism.

The Ottoman state’s leadership of the Muslim world had been acknowledged by the Malays in distant South-east Asia, but internal discontent and the outbreak of world war one provided a pretext for Arab nationalists to revolt. In return, European powers agreed to support an independent and united Arab state. Instead, the British and French carved up the Ottoman empire for themselves. Zionist colonisation of Palestine must be situated in this context of Europeans establishing forms of political and territorial control over former Ottoman lands. The British took over Palestine as a “Mandate”, and as per the 1917 Balfour Declaration promising the Jews a “national homeland” there (without Arab consultation), provided a system for mass Jewish immigration and settlement. Under British cover, Zionist militias seized land and depopulated Arab towns and villages. The Balfour Declaration’s second-half, saying “nothing shall be done to prejudice the civil and religious rights of existing non-Jewish communities in Palestine”, continues to contradict Israel as a Jewish-supremacist state.

Attending this recent past contextualises why Singaporeans have developed distinct relationships with modern Palestinian history, that aren’t reducible to their membership in religious groups programming them to act in ways they “always” have. Policing discussion in the name of preserving “racial and religious harmony” removes what’s happening from its material, historical reality. For we are in fact, in history, and for Palestine this has been described by scholar Rashid Khalidi as “a colonial war waged against the indigenous population, by a variety of parties, to force them to relinquish their homeland to another people against their will.” Singapore is no outsider to this history, embroiled as we were in the 20th century’s battles over who had a right to a homeland.

Local Muslim support for Palestinians resisting Zionist occupation dates roughly to the waning days of British rule there. Muslims in Malaya, a fellow British colony, kept up with news of rising tensions between Palestinians and Jewish settlers from Europe. They read about the actions of key Arab nationalist leaders, including the Jerusalem mufti Amin al-Husseini, whom Harun Aminurrashid called a “great freedom-fighter” (pejuang besar). Key to this interest was the role of Islamic leaders, media, institutions and networks in building anti-colonial movements across Asia from the late 19th century. Muslim intelligentsia from Cairo to Singapore urged their societies to rise against European domination.

Colonial officials in British Malaya and the Dutch East Indies, fearing the mobilisation of their subjects against them, portrayed Islam and Arabs as a subversive foreign influence on hapless “native” Muslims. Never mind that Arabs had been both opponents and collaborators of colonial rule: the gentlemen-sayyids of British Singapore served as community representatives and Justices of the Peace. Yet that stereotype echoes today, in ominous terms like “Arabisation”, or the trope of Singaporean Malays’ divided loyalties. Nowadays our ministers speak of Singaporean Muslims as a “model” of success, thanks to the nation’s guiding hand. That Islam was once a resource for radical action, in response to unequal structures, is buried under the narrative of a clash between Western (thus secular) and Islamic “civilisations”.