September 2022, Dublin. My partner and I had just moved from Shanghai to the Irish capital, where I would start a four-year PhD programme. The week we arrived, leaflets posted through our door invited us to a neighbourhood block party that weekend. “Nothing like this ever happened in our four years in Shanghai,” I remarked to my partner. That weekend, we drank wine on the street and got to know our neighbours. When we were about to leave, I spotted a police van parked at the end of the street. “Do you think the police is here because of a noise complaint?” I asked someone. They looked incredulous. “No, dear. The Garda is here to help block the road, and it’s good fun for the kids. Go see.” I found half a dozen children piling onto the police van, trying on Garda vests, and having their pictures taken by beaming parents.

Later, I kept asking myself why I instinctively linked police presence in the neighbourhood with wrongdoing. Perhaps it boils down to my upbringing in Singapore, where I largely perceive police as interlocutors in community disputes. And that, if I may go a step further, is a by-product of a brand of paternalistic authoritarianism that stunts its charges’ ability to develop the emotional intelligence and social skills to settle their own disputes. We are, in Lee Kuan Yew’s words, a nation of “champion grumblers”. Grumblers, mind you. Not a nation of shopkeepers (Napoleon Bonaparte in describing England), nor a nation of civic organisers (political scientists Theda Skocpol, Marshall Ganz, and Ziad Munson in describing the US). We complain, and wait for things to be done for us, because our imaginations are circumscribed; the possibilities of alternative configurations of people-to-people ties and state-society relations are limited.

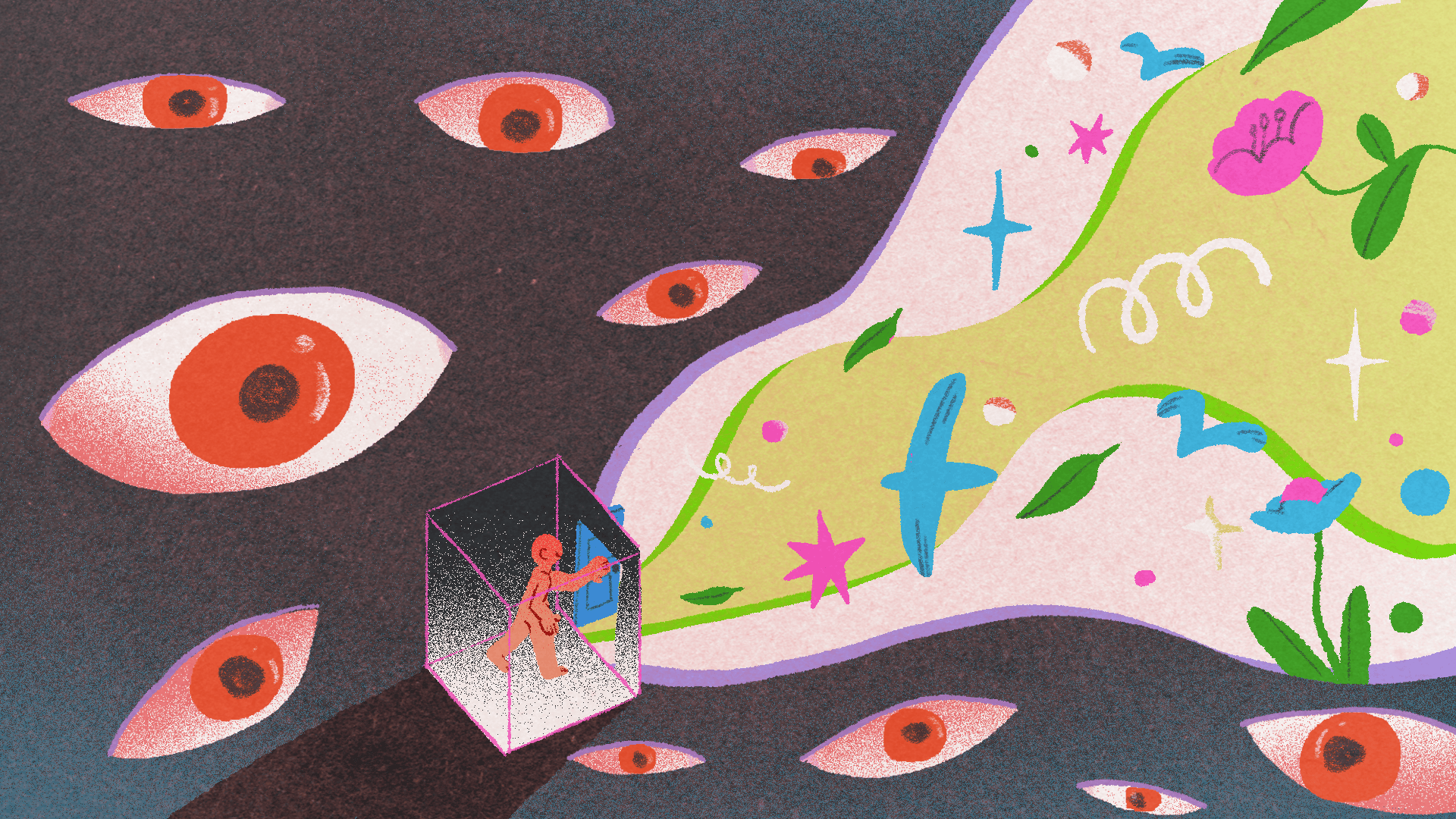

Moments like these, in which I find myself out of step with the people I’m conversing with, began to reveal to me that I may possess an “authoritarian brain”. What do I mean by that? Merriam-Webster defines being authoritarian as “favoring blind submission to authority”, while Oxford defines it as “believing that people should obey authority and rules, even when these are unfair, and even if it means that they lose their personal freedom.” To me, having an authoritarian brain means that you are inclined to unquestioningly comply with authority, to the extent of policing others who are non-compliant. It also extends to possessing a reflexive, under-examined tendency to forsake deliberation and pluralism, for top-down approaches that are more expedient and pragmatic.

This (unintentional) awakening was years in the making. Leaving the homeland was the first step. After growing up and living in Singapore for 31 years, I moved with CNA to China. There, I experienced what it means for a state to have absolute power over your life. Months of harsh lockdowns in pursuit of “zero-Covid” in the spring of 2021 radicalised not just me, but thousands of middle-class urban Chinese who had come of age amid rising national power and prosperity. Most of these disillusioned middle-class Chinese had hitherto been content with the mentality of 岁月静好 (the years are peaceful and the world is stable), which refers to an approach to life that avoids discussing or acting on social problems—aimed, ultimately, at self-preservation within a highly politicised environment. However, the realisation that one can do their utmost to conform and comply, and still feel the full force of the tyranny of the state—for example, by not being able to access food and medical treatment—proved to be transformative. After winter 2022, when zero-Covid restrictions ended abruptly without any meaningful justification of the end they had served, many Chinese made plans to leave, emigrating to North America, Western Europe, and Singapore. It was a vote of no-confidence in China’s direction, perceived to be increasingly determined by ideologues instead of technocrats.

Moving countries reprogrammes you in myriad ways. What you know about the workings of society—including neighbourly bonds, police-civilian engagement, and other aspects of state-society relations—may no longer apply. So, you unlearn some things. And you learn new things—the rights you have, and the standards of civility and other behavioural norms—so that you can fit in. Having now lived outside of Singapore continuously for the last six years, the distance I’ve put between my homeland and myself has enabled a better understanding of my relationship with Singapore. I see the changes that I have undergone and am still undergoing. I am also more aware of entrenched ways of thinking and subconscious patterns of behaviour.

The expression authoritarian brain is inspired by academic Bok-bin Tsioh’s book, 台語解放記事 (Chronicle of the Emancipation of the Taiwanese Language), which I picked up in Taipei early this year. He calls on the Taiwanese to reprogramme their “Chinese brain”, and to challenge the narrative planted by the Kuomintang dictatorship that Hokkien, Hakka, and Formosan languages are inferior to standard Mandarin. It’s a reference to neuroplasticity—the brain’s ability to reorganise itself by forming new neural pathways throughout life and in response to experiences.

Research on neuroplasticity shows that unlearning habits and creating new behaviours is possible. This language of rewiring and reprogramming is apt to describe my experiences of interrogating ingrained patterns of thinking and behaving. Some of my views have strengthened over time and others have come under question. For example, I’m in favour of a strong state with social democratic underpinnings, which I think Singapore possesses. And I’m more convinced than ever that our multiculturalism, however flawed, is incredibly precious. But I think in general, I forfeit too much of my right to participate, to deliberate, and to ask questions, for the sake of speed and efficiency. For example, I was raised to be proud of Singapore’s bilingual language education policy, and I am a beneficiary of it. My fulfilling international career rests, to some degree, on my ability to float between cultural and linguistic worlds. But that should not stop me, as it long has, from questioning how it came to be that I am fluent in two imperial languages, but barely conversant in my own mother tongue, Teochew.

The term “introjection”, from psychotherapist Philippa Perry’s 2012 book, How to Stay Sane, can help us understand how our brains are wired. Introjection, according to Perry, refers to the unconscious incorporation of the characteristics of a person or culture into one’s own psyche. She explained, “[w]e tend to introject the parenting we received and carry on where our earliest caregivers left off—so patterns of feeling, thinking, reacting and doing deepen and stick.” I believe that to be true. Like many Singaporeans of my generation, I was raised in an authoritarian family culture where children are meant to be seen and not heard. Later in life, above that is layered a wider authoritarian political culture and social milieu, where people are co-opted through meritocracy and herded into their stations in life. In my opinion, this results in adults who aren’t able, aren’t willing, or simply aren’t used to expressing what’s on their mind. Establishment elites have lamented this—usually in relation to how Singapore, used to punching above its weight in areas like international law and foreign affairs, doesn’t produce enough CEOs at big multinationals. Former EDB chief Chng Kai Fong attributed this to the way Singaporeans are wired, including not being outspoken enough in international settings.

Living in Dublin, I’ve often been struck by the conversations I overhear between parent(s) and child(ren). There is so much acknowledgement of a child’s agency and autonomy. This often manifests in children who are articulate, self-directed, and more in touch with themselves. These traits position a person to have healthy relationships with themselves and others. Decadent Western parenting, I can imagine some Singaporeans responding. We are Asians, and we have this thing called “Asian values”. In my opinion, I’d rather guard against the essentialisation or racialisation of values, and instead focus on developing key skills for life. We are socially constructed beings, but we haven’t been equipped to think critically and to question our frames and constructs.

October 2023, Dublin. In the days after former Chinese premier Li Keqiang died, some Chinese social media users posted that they were listening to Malaysian singer Fish Leong’s 2005 hit, 可惜不是你 (It’s a pity it isn’t you). In some cases, the character 你 (Nǐ) had been photoshopped with the homophone 尼 (Ní), shorthand for Winnie the Pooh, and a reference to Chinese leader Xi Jinping. I was explaining the humour and creativity of these Chinese social media users to my partner as we walked to get lunch, when three women, who looked East-Asian, passed us. I clammed up. There are few Asians in our neighbourhood, so their presence made me suspicious. I had not only spoken of “He who must not be named”, but I had also told a funny story about how he was being disrespected. Is the internalised fear of the state still within me, even though I no longer live there? Is that why I was on guard against potential informants—in reality, women who were just making their way to a Korean restaurant—who might report or denounce me?

I lived in Shanghai for nearly four years, and from 2018 to 2020, I served as a foreign correspondent. Within a Marxist-Leninist system that demands a monopoly over information, foreign journalists are persons of interest whose ability to access the country is strictly vetted and controlled by a media accreditation regime. Although most newsgathering doesn’t involve investigative journalism, every journalist I knew experienced routine physical surveillance and harassment by state actors in the course of reporting. I was once accused of being a spy and confined to a hotel room for several hours while local police investigated.

I think a lot about why I reflexively policed myself when I had done nothing wrong. Perhaps I haven’t shaken off the social conditioning that calls on me to be hyper-aware of political correctness and red lines in the eyes of the Chinese state. In China, where the main source of group identity is the nation, researcher Xiaoxiao Shen found that people tend to have higher social identity needs and higher ego-defensive needs (to preserve self-esteem), while their value-expressive needs to express core personal values) are lower.

I wonder how I, and Singaporeans in general, would rate on Shen’s scale. I assume we’d probably have similar psycho-social needs to the Chinese. That, along with cultural affinity for Singaporean Chinese, and a shared history of subjugation by Western imperialist powers, might suggest that on the whole Singaporeans are more likely to back authoritarianism and eschew liberal ideas. Indeed, recent Pew surveys in 2021 and 2024 show that Singaporeans are alone among those from high-income countries in viewing China in a better light than the US.

It is not my intention to equate China with Singapore. That would be unfair to Singapore, whose citizens enjoy broader political freedoms than do citizens of China. What I’m trying to get at, is that there are similar pathologies of the state that are at work, including the tendency to monopolise control over information; the idea that criticism should not be aired by everyday citizens in the public sphere, but between elites and behind closed doors; and the belief that the function of the press is to explain, and engender support for government policies. These pathologies, I argue, result in a sealing-off of people into themselves. Similar to the concept of 岁月静好 in China, Singaporeans focus on staying within their lanes, on material accumulation, and on their private lives, because over time, the state has taught us that advocating for anything other than your own self-interest is pointless or even personally ruinous.

This authoritarian culture that is pervasive in our body politic impoverishes us as individuals, in circumscribing possibilities and imaginations, including what it means to be Singaporean. But there are larger consequences. As a scholar of authoritarian politics who specialises in Chinese censorship and propaganda, I perceive the split between Singaporean elites and Singaporean laypersons on China (including the Terrex incident and challenges to international law in the South China Sea), and on Ukraine, as deeply troubling.

To my mind, the split is rooted in authoritarianism in the domestic context. By and large, due to our market economy, we cherish international law and due process in business transactions and international affairs, but domestically, the citizenry has internalised the doctrine that might makes right, that the People’s Action Party (PAP) is the final arbiter on many things. At the minimum, people retreat inwards and concentrate on themselves and their immediate circle. At the more extreme end, people tend to side with the powerful and with what’s expedient. They put self-interest before principles and the national interest.

I saw this happen in 2016, when Lee Hsien Loong, in his National Day Rally, had to spell out why Singapore needed to be vocal on the South China Sea: “...the [g]overnment has to take a national point of view, decide what is in Singapore’s overall interests. We want good relations with other countries if it is at all possible, but we must also be prepared for ups and downs from time to time.” I saw this happen again when Russia invaded Ukraine, because even though I live in a liberal social media bubble, my father frequently broadcasts pro-China/pro-Russia opinions—circulating in his private Whatsapp groups—including the familiar trope that Ukraine should surrender to Russia to save lives as well as taxpayer dollars for the world.

Chinese chauvinism is very much a part of the equation. Notwithstanding elements of ethnic Chinese supremacy in Lee Kuan Yew’s words and policies, Singapore has always had an Anglophone ruling elite committed to multiculturalism, which worked hard to curb grassroots Chinese chauvinism. To my mind, the state has evolved from one that interferes constantly in the private lives of Singaporeans, to one that appears more tolerant of other voices in society, including civil society movements like Pink Dot, and progressive advocates like Workers Made Possible and SG Climate Rally. Although meaningful change can be circumscribed—like in the 377A repeal, where the state foreclosed the possibility of legally recognising same-sex marriages even as it decriminalised gay sex—I choose to see these small steps as wins for progressive-minded Singaporeans.

But I feel conflicted. I would like Singapore to be more democratic, but I am also skeptical of the ability of democracies to defend themselves against the rising threat of sharp power from autocracies. An example of sharp power would be China’s use of potential proxies, like Philip Chan, to influence narratives and debates in a foreign country. In more democratic societies where freedom of expression enjoys greater protections, it might be difficult for the authorities to take meaningful and decisive action, as Singapore did, with the Foreign Interference Countermeasures Act (FICA). However, there is also a risk that the spectre of foreign interference could be used to police perceived threats to state power, such as when the Singapore bureau chief of The Economist endorsed this magazine as an alternative to the state-supported press.

January 2024, Taipei. As part of my research into foreign disinformation campaigns in Taiwan, I interviewed a civic-tech organization, Cofacts, which had developed a crowd-sourced chatbot for debunking disinformation. The chatbot’s 2,400-strong volunteer base verifies or debunks content that users upload for fact-checking. When disinformation is detected, the debunking happens on a one-to-one level, or within private chatrooms on LINE, the main social media app in Taiwan. “Why not report the content to LINE and get them to take down the disinformation? Surely it’s more efficient to take down disinformation, than to debunk it,” I asked. Billion Lee, the co-founder of Cofacts, frowned. “We don’t make take-down requests as it amounts to censorship.”

I get where Billion is coming from. She doesn’t want Cofacts, or LINE, or anyone else, to be the arbiter of what gets published. It’s an argument for freedom of expression, which I sympathise with. But I am not sure that we should back freedom of expression when certain prerequisites do not exist, for example, an informed and media-literate citizenry committed to checking their cognitive biases, and to utilising critical thinking skills when processing information. This is another trait of the authoritarian brain, I suppose. A belief that people are incapable of making sound personal choices means that I tend to see state power and state interference as essential in helping citizens navigate the world.

We went through the same thing again, when I asked what can be done to engender greater accountability within Taiwan’s deregulated commercial media landscape, which has been described by Reporters Without Borders as “dominated by sensationalism and the pursuit of profit”. I was thinking about top-down, punitive measures like Singapore’s Protection from Online Falsehoods and Manipulation Act (POFMA) and Germany’s Network Enforcement Act, which bans online hate speech and requires social media platforms to remove or block unlawful content. But she suggested that the public can collectively increase support to investigative media that is independent and subscription-based. Billion’s answers—in always insisting on not shutting down or cancelling voices, including potentially nefarious ones, from society—reveals her trust in the democratic process, and in good-faith dialogue and debate with her fellow citizens.

I went to bed that night wondering why I’ve tended to side with methods that are expedient, rather than methods that are inclusive and pluralistic. Perhaps I have internalised the familiar rhetoric about the inefficiencies and chaos of democracies, that I am unable to tolerate the innate messiness of the human condition. But it also has to do with my lived experiences—being born in a strong state with strict social controls has worked out fine for me, by and large. This individual-level success, coupled with a lack of possibilities in the civic space, tends to blind me to those whom the system regularly fails, such as migrant workers, or punishes, such as rights activists. It’s also blinded me to other possibilities, to other ways of doing things that can be more inclusive, more democratic, or more equitable.

What can I do then, with my authoritarian brain? It is very much a part of me, and there are of course, many things about our authoritarian city-state that I support. Ethnic quotas in housing estates, just to give an example. But I think it’s important to be open to blind spots, unintended consequences, and alternative ways of thinking and doing. In doing so, I am possibly reconfiguring parts of my “authoritarian brain” to modify beliefs or behaviours—such as a tendency to be incurious and uncaring about things that don’t impact me materially and directly.

I know there will be naysayers. Some will say, “What then, if I reconfigure my ‘authoritarian brain’? I am just one individual,” while others will point to how even the tiniest acts of civic expression can be interpreted by the state as potentially illegal, and by fellow citizens as risky expressions of dissent. It is exactly this sort of thinking, or wiring, that fosters the sense of apathy that keeps us from imagining and creating a better version of ourselves and of Singapore. How do we react when we see racism and chauvinism in action, for example? Are we ready to do what’s hard and laborious, such as engaging bigots, or do we want the state to police egregious behaviours for us? What is our duty as citizens who have pledged to “build a democratic society, based on justice and equality”?

Not everyone has to become an activist. Rather, one can think about having a greater say in shaping your environment, and perhaps supporting those who are willing and able to exercise their voices. We can work towards abolishing toxic status quos, and forging healthier relationships with ourselves, with others, and with the state. There is a historical path dependency to all of this, of course. In China, for example, the idea of a more human-centred communism was debated in the 1970s-80s. According to philosopher Donald Munro, Chinese Marxists at the time argued that “[t]he individual can and should be in control”, and wished for China to “acquire the perspective of the European Enlightenment, wherein the beliefs of individuals do not need to be determined by gods, destiny or rulers”. Hard-liners, who believed that individuality and human agency should be subjugated to the needs of the party-state, won out.

What was Singapore’s path, and which were the moments in history, where the state had opportunities to make different choices, but instead doubled down on OB-markers and knuckledusters? We are told that everything the party-state does is correct and in our best interests. What about acknowledgement of, and recompense for injustices the state perpetuated during security operations like Operation Coldstore, and Operation Spectrum? The PAP has maintained that the arrests weren’t politically motivated but were due to subversive activities which threatened national security. Although public discussion on repressive state actions is not forbidden like in other authoritarian states, official documents remain classified. And for the former detainees, there is yet to be any national reckoning and reconciliation.

I think the act of leaving home helped me recognise the things about myself that I want to reprogram or rewire. Having never truly experienced state repression nor felt what it was like to be a visible minority in society, I experienced both things when I moved to China and Ireland respectively. Intense media repression radicalised me, and the sense of marginalisation in a homogeneously white society opened my eyes to how a large chunk of my life’s smoothness has got to do with being part of the ethnic Chinese majority. While these experiences are unique to me, I feel the lessons I have drawn have universal applicability. There are things to make better, and we have some agency, if only we would exercise it. I draw comfort from the words of the civil rights activist James Baldwin, who wrote, “I am what time, circumstance, history, have made of me, certainly, but I am, also, much more than that. So are we all.”

What can be done? Democracy is not necessarily a panacea. (There are limitations and problems with these scholarly regime type labels, but that’s for another essay.) Democracy is on the decline worldwide, with the Varieties of Democracy Institute saying that 2023 marks the first time in two decades that there are more closed autocracies than liberal democracies in the world. But democratic decline, and the rightward shift in politics that animates it, isn’t all that relevant to Singapore. I see the rightward shift in Western countries as a response to the failure of the liberal democratic system to curb the excesses of capitalism.

This analysis isn’t too applicable to Singapore, because instead of a liberal democratic system, we have a market-oriented economy tempered by an authoritarian/communitarian system with socialist leanings, that intervenes “aggressively” to improve redistribution and social mobility. If we were to situate Singapore between China and the US socio-politically, perhaps Singapore is authoritarian politically, like China is, but on the social front it is pluralistic, like the US. I believe that Singapore’s strength—and bulwark against foreign interference—is that we possess a genuine civic nationalism (as opposed to an ethnic nationalism) that emphasises openness, diversity, tolerance, and multiculturalism.

To forge a healthier relationship between people and government, we all need to be clear and honest about who we are as a nation and as a people. Can the state be better at acknowledging and owning what it is, instead of denying government interference in mainstream media, and engaging in whataboutism when it feels it is unfairly criticised? Even though there may not be immediate incentives for the state to be self-critical, I believe that in the long-run, honest dialogue can help address trauma experienced by various groups, allowing the nation to take steps forward, and become more psychologically resilient. We have a unique model with a lot to be proud of, and I think Singaporeans deserve not to be talked down to, but to be trusted to understand the nuances, contradictions, and trade-offs at play.

In “Two Concepts of Liberty”, philosopher Isaiah Berlin distinguishes between a negative and a positive sense of liberty. Negative liberty refers to the absence of obstacles, barriers or constraints. Liberals generally believe that if one favors individual liberty one should place strong limitations on the activities of the state. Positive liberty, by contrast, refers to acting in such a way as to take control of one’s life and realise one’s fundamental purposes. For the individual or collective to be able to self-realise, critics of liberalism say state intervention is often required. It seems to me that authoritarian states operate more on the basis of securing positive liberty. This means that the individual is subordinated to an abstract collective good, which could refer to things like equal access to education, or the freedom to live in an environment without anti-social behaviours like violent crime.

Democracies have a problem with the emphasis on positive liberty, because the collective imposes on the individual an understanding of what is good and right. But neither approach is perfect; we have to strike a balance between the two types of liberty. As a Singaporean living in Western Europe, I appreciate how an emphasis on positive freedom back home—backed up with laws and collectivist social norms—means that individuals are more likely to obey mask mandates during Covid or voluntarily mask when they are ill. This ensures that the individual’s freedom to not do something (for example, comply with a mask mandate) does not take precedence over the freedom of others (for example, immunocompromised people) to stay healthy and safe. However, we must also bear in mind that in championing positive liberty, autocracies frequently exempt state power from scrutiny, and can dictate what the collective good is, without public consultation.

And what can individuals do? In Exit, Voice and Loyalty, economist Albert Hirschman argued that managers of firms and organisations find out about their failings via two routes: the exit option, which is when the firm’s customers stop buying its products or members leave the organisation, and the voice option, which is when customers or members express opinions about what should change. Hirschman argues that voice is more difficult and costly than exit, so when people choose to use voice instead of exit, that is evidence of loyalty to the group, which can be a firm, an organisation, or a state. Thus, loyalty plays the role of slowing down exit and allowing voice to function properly. To that end, I have two suggestions.

Let us question our existing constructed selves and reclaim narratives. We can use heuristics, like being aware of confirmation bias, or adages like “two opposing ideas can be true at the same time” to help us process information, and counter simplistic and binary thinking. It is not going to be easy reconfiguring the authoritarian brain. We don’t want to be defined by others, so we interrogate our conditioning and preconceived ideas, but at the same time, we want to hang on to our core identity and sense of self, even as it evolves. Returning to the concept of “Asian values” as an example, we need to recognise that it is first and foremost an ideology used to counter pressures to democratise by invoking cultural difference and by framing democracy and certain liberal values as “Western”.

There are historical parallels. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, scholar Mark Thompson noted, ideologues in Imperial Germany distinguished between Western civilisation and German Kultur, arguing that “industrialisation ought not to lead to democratisation, for democracy was alien to German culture.” Thompson’s comparison of the German Kultur argument with the “Asian values” argument reveals that the real issue involved is not Asia versus the West, but authoritarian versus democratic modernity. Second, within the Singaporean context, Lee Kuan Yew’s construction of “Asian values” draws heavily from the statist Confucian-Legalist tradition, and ignores other Asian philosophies and schools of thought, including Hinduism and Islam.

Even if we were to agree that liberal traditions and ideals of human rights originating from the Judeo-Christian West are not universal and not generalisable to Asian societies, there are important contestations and evolutions in say, Chinese philosophy alone, that are left out of “Asian values”. Take Zhuangzi (3rd-4th BC) for instance, who championed the idea of personal freedom. “Asian values” may have earned plaudits back in the day as a sign of Asians being able to talk back to the West, but today, it is obsolete, and a reflection of how identities were constructed in an earlier age.

Finally, let us reject political apathy and commit to greater civic engagement. This can mean advocating for causes you care about, through modest, everyday behaviour, like practising active allyship, or writing to your MP. We lobby our MPs to get the public goods (sheltered walkways and public housing) we want; why not also lobby them to get the values we want reflected in policy making? In her seminal 1975 essay “Politics in an Administrative State: Where has the Politics Gone?”, Chan Heng Chee, academic and now Singapore’s ambassador-at-large, describes Singapore as possessing a thoroughly depoliticised citizenry. In her appraisal, following separation from Malaysia, depoliticisation became a “conscious, explicit philosophy” of the state, with measures “initially enforced to suppress the communists…result[ing] in the control and limitation of all political activity other than those of the ruling party”. Nearly fifty years on, and having apparently transitioned from third world to first within a single generation, very little has changed. This is not only an unhealthy state-society dynamic, but also unhealthy for us as individual citizens.

“To refuse to participate in the shaping of our future is to give it up,” said American civil rights activist Audre Lorde. “Do not be misled into passivity either by false security (they don’t mean me) or by despair (there’s nothing we can do). Each of us must find our work and do it.”

Linette Lim is a PhD candidate at University College Dublin. She uses mixed methods, including experiments and computational text analysis, to study information manipulation in authoritarian regimes. Her X (formerly Twitter) handle is @LinetteMLim

Letters in response to this piece can be sent to sudhir@jom.media. All will be considered for publication on our “Letters to the editor” page.

If you enjoy Jom’s work, do get a paid subscription today to support independent journalism in Singapore.