Raja reaches London at the end of August 1935. It’s been a long sea voyage from Singapore on the S.S. Rawalpindi, calling in at Penang, Colombo, Aden, through the Suez Canal into the Mediterranean, then sailing up through the Bay of Biscay. But the Londoners he meets can’t really understand how far he has come. Did you have a good crossing, one of his closest friends will describe an English landlady saying, as though he’d just arrived here, at the hub of the Empire, what she sees as the centre of the world, by traversing the English Channel, or making a trip on the Tube, on the Northern Line from Edgware to Kings Cross.

In London, the daily journey that he makes is more modest, from his boarding house on the fringes of Hampstead to Belsize Park tube station, and then to Charing Cross. In the first years he studies hard, as all colonial students in the metropolis seem to do. He has come to London to read Law at King’s College, at his father’s request and on his money. His brother will stay in Singapore to study Medicine. In the library, and in his room at night, he annotates his books using a dictionary to enlarge his vocabulary. He glosses acerbic as harshness of speech, viviparous as bringing forth young alive, phylogeny as the origins history of races or types of animals. He passes his exams.

Each morning he wakes slowly, like an unfolding flower. He fumbles and switches off the alarm clock, still half asleep. He opens one eye, then another, and then begins to stretch out his limbs.

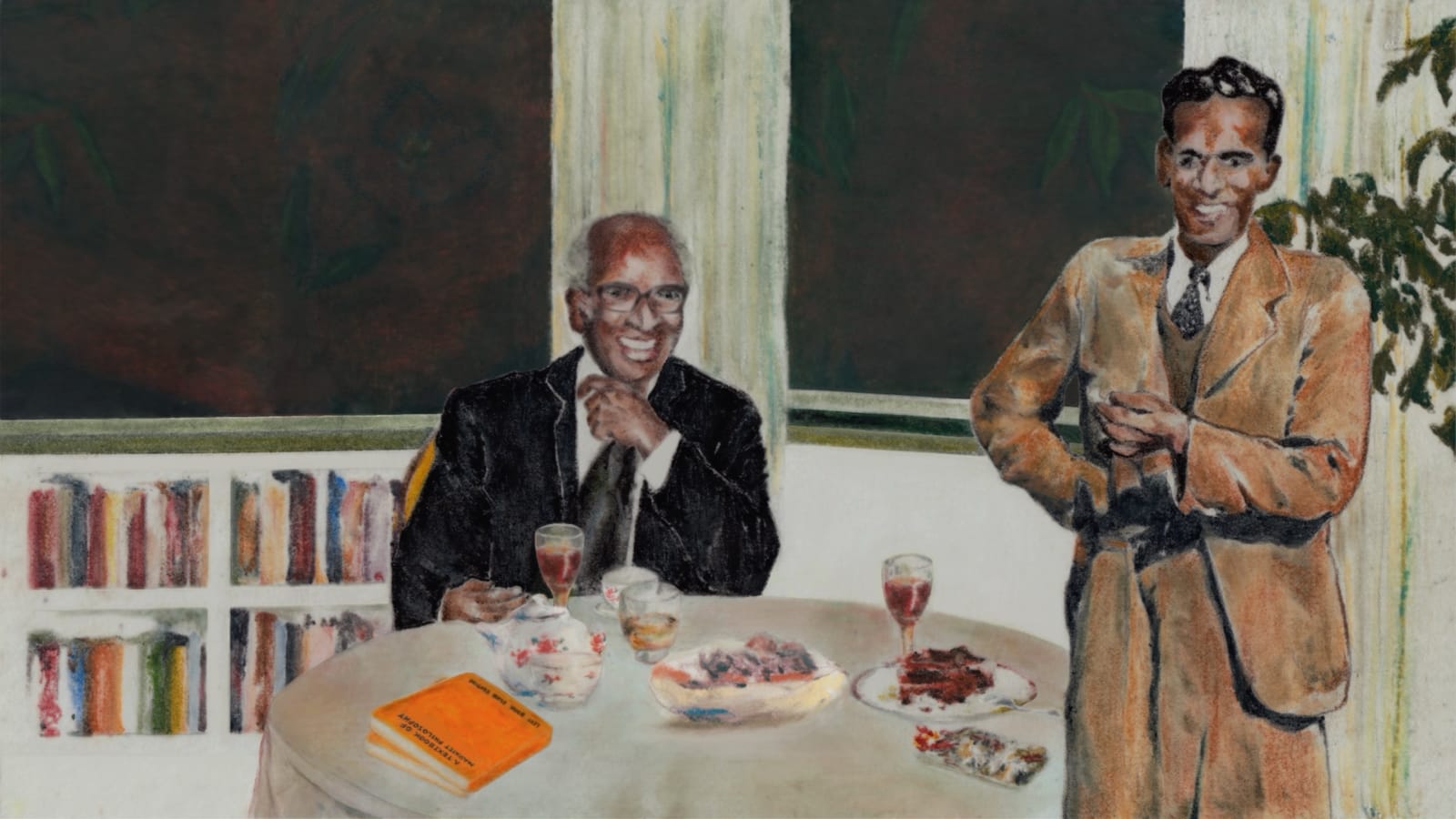

He has never learned to cook for himself. At most he can boil an egg or make tea and things. In his boarding house, meals are served by Mrs Churchill at the big table near the kitchen at the bottom of the house. The boarders descend the steep stairs from their rooms on the upper floors. Other Malayans room here when he first arrives, alleviating the loneliness of the big city, but they soon depart. A stream of other migrants flows through the house: a banker with Kuomintang connections, a student of the violin from Bombay, a Chinese journalist who has taught at the School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS), writes for Ta Kung Pao, and broadcasts for the BBC. Few stay long, but he becomes used to ways of living together, living in difference. His friend Subra, who lives nearby, will write about such spaces, that a select number of boarding houses or hostels that admit non-White residents, and their formidable landladies, next to one of whom he feels like a mouse beside a mountain.

At Mrs Churchill’s table, the boarders chew over and consume the news with food. Both are indigestible. The world is changing for the worse. Italy invades Abyssinia. Japanese troops move from Manchuria into China. Germany eats up Austria, and takes several bites out of Czechoslovakia. Then Poland, and a descent into world war. The planet, Raja writes, is sinking into the primeval swamp of savagery and barbarism, with Hitler as its voodoo-man, its warrior chief.

In history, we often combine storytelling with what psychologist Jerome Bruner called the paradigmatic, or logico-scientific mode of thought. We tell the story of the nation of Singapore as a process of unfolding truth, with an understanding of the past imposed from the present. Bruner contrasts such cognition to what he characterises as a narrative mode of thought, which investigates what he calls the broader and more inclusive question of the meaning of experience. This form of cognition, Bruner suggests, is often expressed in the subjunctive mood: it is provisional, speaking not of certainties but of possible worlds.

The boarders in Mrs Churchill’s house live through a history they struggle to make sense of, and continually revise. Only a week before invading Poland, Germany makes a non-aggression pact with the Soviet Union, its erstwhile enemy; Molotov, the Soviet Foreign Minister, notes that fascism is nothing more than a matter of taste. The ground of history shifts under the boarders’ feet: they can no longer tell themselves the story that made sense only a day ago. Their own histories, too, run through rooms and out of the house, to harbours, airports, and suburban cul-de-sacs, where they braid themselves into larger stories. A brother and a sister transiting through the house will migrate and become Chinese Americans: she will train as a pilot, be held up as a role model. The violin student will return to Bombay to teach violin; another boarder will marry, settle in the Surrey suburbs, and open a Chinese restaurant.

We can follow Raja’s own story further in narrative mode, patching together correspondence, journalism, diaries, colonial office surveillance files, annotations, photographs and more, using a methodology adapted from what historian Saidiya Hartman has called critical fabulation. Hartman’s goal in her work is very different from mine here: she attempts to paint a full picture of the disposable lives of those captured, enslaved, and killed during the Atlantic slave trade, and, in a later publication, the lives of young black women in Philadelphia and New York in the early 20th century, by pushing against the limits of an archive marked by violence and recorded by those in power. In Raja’s case, similar techniques, exploiting, in Hartman’s words, the capacities of the subjunctive, help us untangle an individual history from the larger, dominant one into which it has been tightly woven, to leave a sense of incompleteness, of loose threads rather than flawless finality.