Politics: Elections update

Singapore’s general election (GE) is due by November this year, and rumours are swirling that it could be as soon as May. Lawrence Wong, prime minister and finance minister, is expected to soon deliver an election budget—returning our money to us as vouchers and other handouts—which could soften the ground for the ruling People’s Action Party (PAP). An alternative theory is that Wong, leading the party into a GE for the first time, may wait till after August’s SG60 celebrations, during which Singaporeans will invariably be reminded of our eternal debt to the PAP.

The clock will really begin ticking once the Electoral Boundaries Review Committee (EBRC), convened last month, completes its report, a process that’s historically taken between three weeks and seven months. Critics of Singapore’s relentless gerrymandering will be paying particular attention to any redrawing of the West Coast district—in the last election, the PAP narrowly beat a team from the Progress Singapore Party (PSP), and has since lost its anchor minister there, S Iswaran, who’s been jailed for obtaining gifts as a public servant and obstructing justice.

Ng Chee Meng, whose Sengkang team famously lost to the Workers’ Party (WP) at GE2020, recently confirmed to The Straits Times (ST) the party’s worst kept secret: he’ll likely try his luck again, though seemingly in a different district. It’s clear that party elders like Ng—despite him failing to win an electoral mandate in 2020, the National Trade Union Congress (NTUC) controversially kept him on as secretary-general, a role that since 1980 had been filled by cabinet ministers. The PAP’s Sengkang team, meanwhile, was dealt a blow when Marcus Loh, an energetic candidate who’s been seen parading Labubu dolls and a PAP-branded condolence banner at a funeral, suddenly dropped out, to be replaced by Bernadette Giam, a restauranter. No clear reason was given for Loh’s exit, raising suspicions that the party’s initial screening processes, like in 2020 with Ivan Lim, may have failed.

The slow drift of emerging political talent from the PAP to the opposition has been an ongoing theme for the past 15 years. Hence the party’s liberals may have been chuffed to see Deryne Sim, an intellectual property lawyer, queer activist and former committee member of Pink Dot, on walkabouts with K Shanmugam, law and home affairs minister. Sadly, Sim’s queer activism has now drawn the ire of conservatives in Singapore. As the PAP attempts to broaden its appeal to progressives, there’s a risk it gets outflanked on the right by parties courting the conservative religious vote—a relatively minor, though terribly depressing electoral dynamic in a “global city” still filled with prejudice against our queer community.

Some further reading: In “The system has stopped evolving: why Harpreet Singh joined the opposition”, Jom profiles the senior counsel who has joined the WP.

Society: Rage against the dying of the light

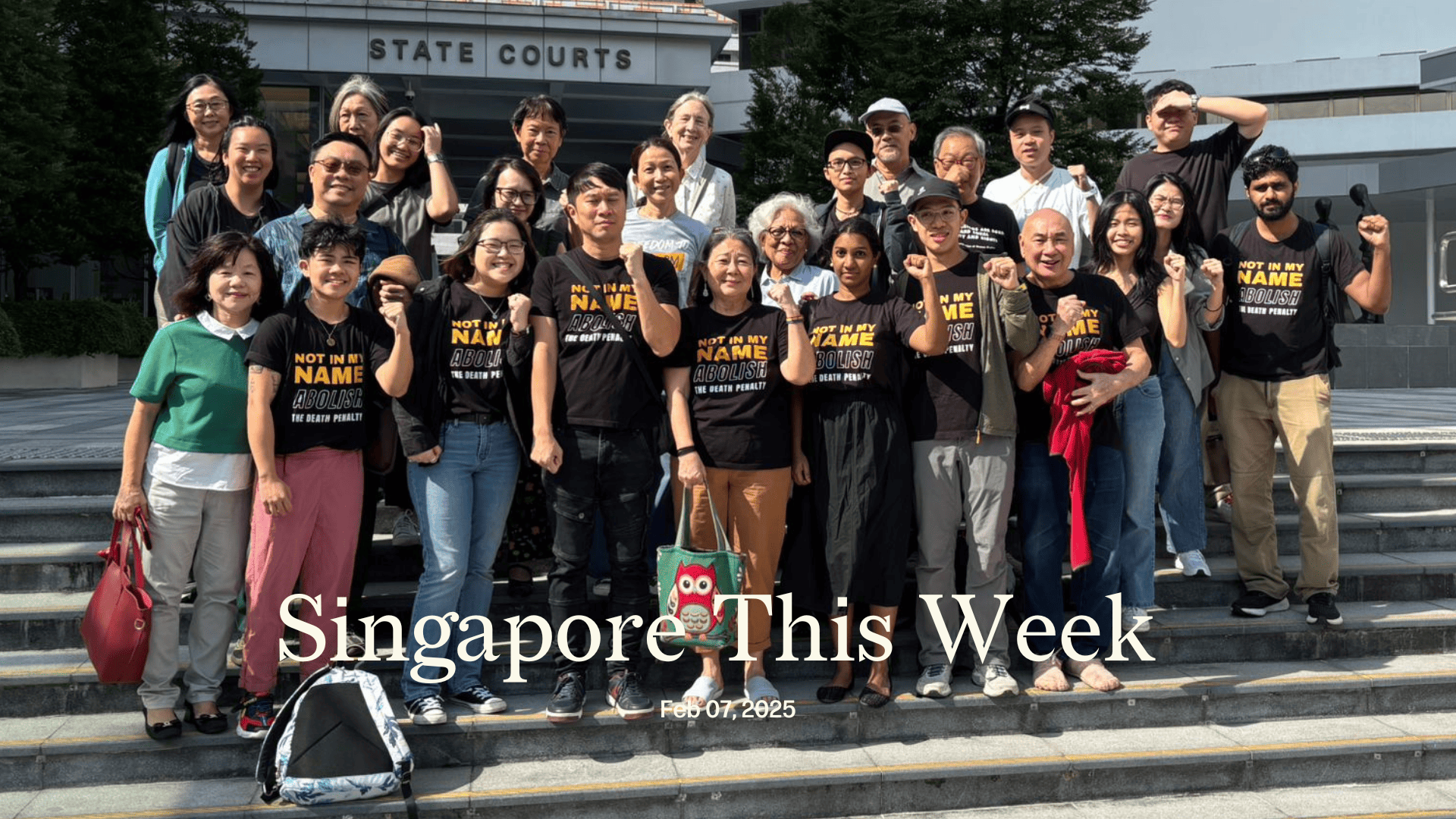

Critics, beware. Another sign that the GE may be approaching is the crackdown against activists. Last month we reported on the steady crippling of the Transformative Justice Collective (TJC), which had taken offline its popular website and Instagram pages after the government designated them as declared online locations. TJC has received numerous correction directions under the Protection from Online Falsehoods and Manipulation Act (POFMA), all for its death penalty reporting. (Many have questioned these orders, including lawyer Yeoh Lian Chuan.)

Worse, this week TJC said that it and three members are also facing criminal investigations under Section 7 of POFMA. Even though TJC had complied with the three POFMA orders in question, the worrying Section 7 permits additional action if it’s shown that the communicator of the alleged falsehoods knew or had reason to believe that it is indeed a falsehood, and if the falsehood’s spread could undermine Singapore in several ways, for instance being prejudicial to our national security. If convicted, TJC faces a maximum S$500,000 fine; and the three individuals a S$50,000 fine and/or five-year imprisonment.

Also this week, the government charged activist Jolovan Wham under the Public Order Act for taking part in five candlelight vigils for prison inmates on death row. “Your Honour, it is the state who should be on trial, not me. I didn't kill anyone,” said Wham in court. A video Wham posted last month shows the absurdity of the situation—a fumbling police officer, ordering several Singaporeans to extinguish two candles along a sidewalk outside the prison at night, is unable to even articulate what the offence is. Wham pointed out that Singaporeans light candles regularly during the seventh month of the lunar year, the so-called Hungry Ghost Festival. They don’t do it outside the prison, replied the officer. Perhaps Singaporeans are only meant to mourn those long departed—not those we’re about to kill.

Some further reading: last month Jom argued that Shanmugam is wrong about the death penalty. There is no conclusive evidence to support its supposed deterrent effect.

Society: Spreading the Word, one mall at a time

Orchard Towers has a new occupant, a church. Some may proclaim this a “Godsent!”, as management tries to clean up the mall’s racy image. Bought for S$54.5m, Cornerstone Heritage—which runs Cornerstone Community Church—now owns two units measuring more than 19,000 sq ft on the fourth floor. In a statement online, Yang Tuck Yoong, the church’s senior pastor and co-founder, referred to the venue’s ignominious nickname, “The Four Floors of Whores”, and Cornerstone’s history of “redeeming a place from its dark past”. Once “a stronghold of the enemy”, Yang wrote, the properties are now “being claimed by the people of God.”

Space is essential for doing the Lord’s work, and acquiring prime real estate has been a popular strategy. No coincidence, perhaps, that the Catholic Church is the world’s second largest landowner. Wrote Yang: “[T]he retail units surrounding the auditorium offer space for potential future expansion should our footprint need to grow in the city.” In recent decades, other religious organisations such as New Creation Church and City Harvest Church have set up worship sites in commercial centres. Amenities, public transport options and ample parking are all-important considerations for existing and prospective congregants.

Realty comes at a hefty cost, however. Generous donors, as well as believers of tithing and the “prosperity gospel” enable religious groups, especially megachurches with their thousands of followers, to shell out millions to finance properties in coveted locations. An ST review showed that universities and religious groups topped the list of donations for charities in 2018. The previous year, the latter (including churches and temples) netted S$1bn of a total of S$2.65bn collected. In 2019, Rock Productions, the business arm of New Creation Church, paid an eye-watering S$296m for The Star Vista.

Heaven knows how much capital is enough and when enough is too much? Some have suggested: setting limits as to the amount of funds that religious groups can raise and keep in their reserves; taxing them even if registered as charities; transferring excess wealth to smaller groups; mandating a minimum percentage of total expenditure for donations; and making financial accountability more stringent and transparent. Faith is a lucrative business, but it can lead to ethical blindspots; temptations that even the most devout find hard to resist. Lest we forget the City Harvest Church scandal, money doth corrupt.

Society: Lights out on nights out

Pre-game. Enter club. Dance frantically, drink copiously. Puke, maybe. 4am cheese prata, mmm so greasy. Pass out in taxi. Wake up next morning and wonder: was last night really me? For decades, young people in Singapore have followed this weekend ritual. No more. Gen Zs and millennials are increasingly ditching these bacchanalias, according to ST. Public drinking was the cheap fuel that drove much of the clubbing industry—partiers on lower budgets could pop out to tank up before returning to the dance floors. But that was banned in 2015. Then came the Covid-19 pandemic, wrecking local nightlife for years and making yuppies realise that a good time was not necessarily predicated on shouting oneself hoarse amidst a sea of sozzled souls stumbling to ear-splitting music. Especially when it all became so expensive. Labour costs, alcohol prices, and taxi charges have all soared in the pandemic’s wake. “See the cab fare afterwards will sober,” one Redditor sagely commented.

Two dominant strands have emerged from this pandemic flux. Millennials and Gen Zs are drinking more often in smaller groups at home, or they’re choosing to step out early and return at earthly hours—as indicated by the mushrooming of collectives like 5210PM (tagline: NO LOUD MUSIC AFTER 10PM!) that promise both a good time and a good sleep. And while drinking rates in Singapore largely remained unchanged between 2019 and 2024, an alternate alcohol-free entertainment scene is brewing here too. Ethan Lee, director and barista at Beans & Beats, an outlet that wants to popularise “coffee-clubbing”, spoke about figuring out “an alternative to what we perceive nightlife to be…with alcohol, and combine it with coffee instead. And then also do it in the day time…”

Local disenchantment with nightlife jives with a global trend. The UK, for instance, is losing one club and more than four pubs every two days; drinking rates have also plummeted amongst the young in the US, alongside a steep decline in bar and club revenue. Apart from being weighed down by cost-of-living concerns, younger folks have become more health-conscious and less enamoured of alcohol, with far more options for socialising and entertainment than older generations. Seems like “I got sooo wasted” just doesn’t have the same social cachet anymore.

History weekly by Faris Joraimi

At the launch of Amanda Lee Koe’s latest novel Sister Snake—which I sadly could not attend—the 1993 Hong Kong film “Green Snake” was screened, starring the iconic Maggie Cheung as the namesake protagonist. I decided to watch the film as a little distraction to mark the new year of the Wood Snake. It’s beautiful, camp, and strange, but also manages to say important things about what it means to exist in the world. “Green Snake” was based on the well-known legend of Madame White Snake, revolving around a pair of serpents, one white (Bai Suzhen) and the other green (Xiaoqing), who transform into women after centuries of training to become humans. The pair are sworn sisters. Romance blooms between Bai Suzhen and a mortal man, Xu Xian, so the two get married. A pious monk Fahai learns of the relationship and is determined to rend them apart, believing that their love defies the laws of Heaven. The tale has been popular since at least the 16th century, and remains a classic of traditional Chinese opera in Malaya, typically performed in Cantonese and Teochew. Recent adaptations include W!LD RICE’s Mama White Snake in 2017, blending Peking-style acrobatics with mainstream musical theatre. Technically a sequel, this was my introduction to the tale.

“Green Snake” also feels like a contemporary spin. It’s a horny movie that delights in feral, ungovernable desire: Bai Suzhen and Xu Xian’s affair seldom seems to rise above lust, suggesting that sexual longing and “true” love are two sides of the same silk curtain. The dynamic between the two she-snakes is often sapphic, implying more conceptions of sisterhood beyond biological kinship. Passion humbles all figures of authority. Fahai, despite his monastic Buddhist discipline, gets erections; a Taoist medium who tries to cockblock Xu Xian is the world’s clumsiest ghostbuster; and Xu Xian himself is a Confucian scholar-gentleman distracted from official duties. Each embodies one of the complex, overlapping Chinese traditions that have explored ways to live well for centuries. (It feels crude to call them “religions” or “philosophies”.) We moderns may relate most to Bai Suzhen and Xiaoqing’s quest to be human: free to choose whom to love, to be alive to one’s pleasure and pain. And apparently, only in the Qing dynasty did Fahai’s character change from being a sympathetic hero to an authoritarian religious zealot. It all ends in tragedy. (No spoilers.) But verses sung in the opera, when Bai Suzhen and Xu Xian first meet each other, know that death is no horizon: “At beloved West Lake on a February day, slanting winds and fine rain see off the pleasure-boaters. Ten lifetimes might pass before kindred souls share a boat, one hundred may pass before they share a bed.”

Arts: A restless artist, laid to rest

“There’s not a single day that I do not paint or write calligraphy,” Lim Tze Peng declared a few months ago, aged 103, ink stains on his pants and a huge smile on his face. “Art has given me longevity!” 20,000 artworks later, Lim has finally put down his brush. The Cultural Medallion winner, who was Singapore’s oldest living artist, died earlier this week following a hospital stay for pneumonia. Devoted to his craft and delighted by the world till the very end, the man who witnessed Singapore’s rapid urbanisation through his inks and oils had the rare thrill of witnessing his own legacy make history: his biography, Soul of Ink: Lim Tze Peng at 100, claimed the country’s richest book prize last year and, several months later, he had his first solo exhibition at the National Gallery Singapore. The retrospective runs till the end of next month and shows off over 50 of his works, which share the spotlight with scrapbooks and sketchbooks from his Telok Kurau studio and home. These previously unseen materials constitute his own meticulous “visual dictionary”, in the words of curator Jennifer Lam. Lim favoured thin strokes and delicate washes in his scenes of Singapore past—crammed with detail and painted en plein air—but also thick columns of hutuzi (糊涂字; “muddled writing”) laid on paper with a forceful hand. This was a hand that had scrubbed school toilets while a young teacher, and later principal, of Xin Min School, and also hoisted brushes as thick as an adult’s forearm well into his 90s. Lim wasn’t just a prolific producer of art, he was also a sojourner, painting both under the swelter of the equatorial sun in Indonesian farmland and in the wind-swept medieval villages of coastal France.

He does leave behind one person who kept him company on life’s varied terrain, well before his paintings went for S$200,000 at auction, and when galleries demanded that he paint with “more colours” to make a name for himself. His wife, Soh Siew Lay, raised their six children and a brood of pigs, ducks and chickens on their farm, assisted him on location while he was painting, and often chided her dreamy husband when he spent his solo income on art books and inks instead of the household. He’d always been in awe of her, and frequently acknowledged her sacrifices: “She always said, ‘Art is your first wife, I’m just your second wife’.” Their unspoken affection for each other took a different language: the straightening of a shirt collar, the tightly clasped hands and, later on, his determination to give her dignity when dementia took its toll. This eulogy for him, then, should also be a celebration of her.

Arts: Playwrights going places

Two Singaporean playwrights have just written their own tickets to success: one’s about to take the reins of Singapore’s flagship performing arts festival, the other’s picked up an award for his outstanding new off-Broadway play. But “playwright” isn’t the only role they play. Chong Tze Chien transformed The Finger Players, where he was company director for almost 15 years, from a pigeonholed group for kids to an award-winning puppet theatre company that has gamely tackled mental illness, family feuds, social dramas, political histories—and lots and lots of death. He’ll be inheriting the directorship of the Singapore International Festival of Arts (SIFA) from his peer, Natalie Hennedige. Both artists came of age with The Necessary Stage, where in the early 2000s he was company playwright and she was associate artist. Chong’s creative career has flourished since he relinquished his managerial role at The Finger Players in 2018, where he admitted he’d fumbled the company’s financial and administrative development. He told ArtsEquator that he’d neglected nurturing a younger generation of leaders and managers by not delegating executive decisions, which also led to his own burnout. “I’m the solution—and also the problem, you see. So...I have to take myself out, right?” he conceded when he left. In the years since, both the company and its former director seem to have recovered somewhat. Hopefully this newly minted festival director-designate has learnt a thing or two from that chapter. He’s since embarked on several ambitious cross-cultural experiments, including adaptations of the Mahabharata and Dream of the Red Chamber, and years-long collaborations with Japanese artists. We’ll see where this new role, which he’ll occupy till 2028, brings him next.

Over in New York, Jeremy Tiang—also an acclaimed translator—has made translation the star of his show. His Obie-winning “Salesman之死” transports us to Beijing in the spring of 1983, when Arthur Miller of “The Crucible” fame was invited to direct his own play, “Death of a Salesman”, at the Beijing People’s Art Theatre. He spoke no Mandarin, but the production was a hit thanks to the combined efforts of multilingual Chinese actor Ying Ruocheng and young university professor Shen Huihui. Shen’s the protagonist of the play, which is based on this chaotic multicultural encounter. Here, Tiang chooses to reveal the frictions of cultural and linguistic translation in the rehearsal room over the refined result on stage. It’s a play Tiang is uniquely positioned to write. He’s translated over 30 books from the Sinophone world, was the first Singaporean to make the International Booker Prize longlist for his translation of Ninth Building by Zou Jingzhi, and won the Singapore Literature Prize’s inaugural translation category last year. He told American Theatre: “There’s this idea that if we do our jobs as translators properly, then you don’t notice us at all, which I don’t think is true.” The Obie judges certainly noticed, lauding the work’s “nuanced portrayal of translation and transposition”. Singaporean producers might also want to take note.

Tech: Can Punggol be Singapore’s Silicon Valley?

The Singapore government began developing the Punggol Digital District (PDD) in 2018. This 50-hectare district is designed to integrate businesses, academia, and public spaces, fostering collaboration in cybersecurity, digital technology services, and the Internet of Things. At the heart of PDD, and what distinguishes it from other smart districts, is what’s called an Open Digital Platform, a sort of smart city operating system that will enable different technologies to “talk” to each other. PDD has over 20,000 sensors to track movement, energy and temperature metrics and is one of the few residential towns to host a technology-centric university, the Singapore Institute of Technology (SIT).

Though it’s expected to be completed only in 2026, young families have already started moving into their newly constructed build-to-order public housing flats (colloquially called BTOs), and the first wave of companies is expected to arrive sometime this year. Local technology companies such as dconstruct, which creates navigation systems for autonomous robots, are attracted to PDD’s smart district-wide infrastructure that allows robots to operate in lifts, turnstiles and deliver items. Meanwhile, OCBC Bank previously announced a capital investment of S$500m to create a sizeable technology hub for its employees, and support programmes by SIT.

Punggol’s rich history as a fishing village makes it an interesting choice for a modern, waterfront technology hub. “Punggol” literally means “hurling sticks at the branches of fruit trees to bring the fruits down to the ground”. The PDD holds the promise of boosting local tech talent development and harnessing the ability of companies to innovate. More than that, it’s a grand experiment in futuristic urban design and planning—a town run partly by the machines. ST has called it “Singapore’s take on Silicon Valley”. Let’s pray the machines don’t end up throwing sticks at us.

Tech: Local cybersecurity firm making global waves

Singapore-based Flexxon is pushing the boundaries of cybersecurity by addressing a crucial vulnerability: hardware-level threats. While most measures rely on software updates to defend against known risks, such as viruses, Flexxon’s technology embeds AI directly into storage hardware—Solid State Drives (SSDs), servers, and laptops. It also provides real-time detection and protection against unknown threats. This includes zero-day attacks in which bad-faith actors exploit a vulnerability even before it’s known to the vendor or developer. The shift from reactive to proactive defense allows devices to autonomously lock down during breaches, wipe sensitive data, and even prevent physical tampering. Cybercrime costs are projected to hit US$10.5trn (S$14.19trn) annually by 2025, more than triple from a decade ago. Flexxon’s solutions—like the X-PHY Server Defender—are addressing key pain points, reducing downtime, and restoring data faster, making them invaluable for industries where minutes of downtime can cost millions.

Flexxon, which started life in 2007 as a humble flash drive distributor, has had a remarkable rise since pivoting to cybersecurity in 2018. Today, the company owns 40 patents and has signed numerous partnerships across the globe. It has also entered the US$186.7bn (S$200bn) US market, having made a presentation at the White House in 2022. It exemplifies how Singapore’s small and medium enterprises (SMEs) can adapt to compete on the global stage and build significant intellectual property.

If you enjoy Jom’s work, do get a paid subscription today to support independent journalism in Singapore.

Amendment: an earlier version said that Iswaran had been jailed for corruption. The original corruption charges were eventually dropped.