Society: Not the exam hack we wanted

“How am I going to do my exams? And how am I going to pass my O-Levels in two months?” a Secondary 4 student from the Methodist Girls’ School told CNA. She was one of 13,000 students from 26 schools who realised over the past week that their study devices, like iPads and Chromebooks, had been wiped remotely by a hacker. “It’s very saddening to see a lot of my classmates and even myself lose four years’ worth of notes, thrown down the drain like that and just all gone in an instant.” It sounds like one of those recurring study nightmares that we’re always relieved to awake from. Not this time.

The breach happened through Mobile Guardian, a UK-based application licensed and used by the Ministry of Education (MOE) to help parents manage their kids’ device use, such as setting limits on screen time. The breach affected users in North America, Europe, and Asia Pacific, though according to CSO, a cybersecurity publication, it had “a particularly severe impact” on Singapore. Worryingly, authorities should have seen this coming. On April 19th, MOE announced “an incident of unauthorised access” at Mobile Guardian’s user management portal in the UK. On May 7th, Chan Chun Sing, the education minister, responded to a flurry of questions about it in Parliament, concluding that “MOE conducts independent audits and regular cybersecurity testing”. A Reddit thread published on Tuesday, “Proof of Correspondence with MOE Regarding Mobile Guardian Vulnerability”, appears to show correspondence between somebody who’s discovered vulnerabilities in Mobile Guardian and MOE’s tech department, going back to May 30th. “This would also mean that an attacker can do everything school admins can do,” the letter writer said. “For instance, an attacker can reset every person’s personal learning device.” After the letter writer bugged MOE for a response in late June, the ministry allegedly responded with some boilerplate copy: “We have reviewed the vulnerability report and confirmed that it is no longer a concern.” (MOE did not respond to a Jom question about the authenticity of this Reddit exchange.)

Poor Chan will probably have to answer numerous new questions, from MOE’s seemingly poor internal IT security processes and oversight, to why students’ study data was not backed up, either locally or centrally. At a larger level, it’s another sign that Singapore, the “Smart Nation”, has some way to go in terms of cybersecurity.

Society: She works hard for the money

How rich is Singapore, really? Notwithstanding its flaws as a measure of overall human well-being and progress, gross domestic product (GDP) is still regarded by many as a useful benchmark. Singapore’s politicians have long cited it as a measure of their/our apparently outsized performance. “According to a recent Forbes report, we have the fifth highest GDP per capita in the world by PPP (purchasing power parity) terms. Well ahead of the UK,” boasted K Shanmugam, law and home affairs minister, in April, in response to a commentary in The Economist.

Most GDP analyses, like the above, perform two calculations on a country’s annual “output”: dividing it by population size to get a per capita number; and trying to adjust (PPP) for the fact that a dollar goes further in some places than others. Last month, The Economist published “The world’s richest countries in 2024”, which offered an even more robust assessment—adjusting also for hours worked. This seems reasonable. Surely the person who can create S$1,000 of value in one hour is, in one sense, richer than the one who needs five.

And, just like last year, Singapore’s high ranking plummeted once hours worked was accounted for. “Singapore and Brunei exhibit some of the biggest differences between each measure,” The Economist concluded. By contrast, countries such as Austria, Belgium, Germany, Iceland, Denmark and Sweden rose up the ranking, with the additional adjustment, to outperform Singapore in the final analysis. As Singaporeans try to nurture a society with a more enlightened work-life balance, it’s worth pondering this and other novel measures that can offer more salient insights into the human condition here. Best of all, “Shan” needn’t worry—even after accounting for our long work hours, Singapore is still “richer” than our former colonial master.

Society: Road to AI hell paved with plain incompetence

Netizens recently lambasted the Ministry of Finance (MOF) for a series of AI (artificial intelligence)-generated advertisements posted on its social media platforms, and rightly so. Many were weirded out by the “creepy” and “horrendous” quality of the images: “Is that a streetlight growing out of a tree?” asked one Redditor. Some noted that it resembled a scam ad, which the government has gone to great lengths to warn the population about. Others called out the use of AI in these instances for being sloppy: “Generative AI smells of laziness, has issues with plagiarism and honestly if our public service was professional they should stop endorsing this,” Deliciouswizard opined. One commenter even recreated the ads to show he could do a better job.

MOF explained to TODAY that it uses AI to explore “a different type of visual on top of those done by designers.” It also said that it had placed footnotes on its posts and images to acknowledge the use of AI to “maintain transparency” on the content’s source. That’s all well and good; who can fault a need to experiment with new toys and kudos for being upfront about it. (But the images looked so artificial, it wouldn’t have taken much intelligence to see that AI was involved.) The real problem here is not so much that AI was used. But that it was done with what appears to be so little thought as to detract from the message that MOF was communicating—that there’s financial support for local communities in need, and how to go about getting it.

Food: Makan magic in Mumbai

Mumbai residents can now gorge on authentic Malayan fare. Synthia Lau, a Singaporean who has lived in India for 15 years, has opened an eatery called Makan Lah with the hope of bringing some flavours from our little red dot to the country’s most populous city. In and of itself, this is hardly news. Hundreds of restaurants open in Mumbai every year; hundreds more shut down. Yet, given India’s obsession with food, there is a remarkable paucity of restaurants in Mumbai (and across the country) that offer the city-state’s famed cuisine.

Some hotels serve “Singapore noodles”, a head-scratching medley of chewy noodles, bell peppers, onions, and the occasional green chilli that has probably never been tossed in a wok on these shores. Carrot cake puts many in mind of gajar ka halwa, a hauntingly sweet dessert much beloved across vast parts of the north. Tofu elicits unfavourable comparisons with paneer (cottage cheese), another northern, middle-class passion.

Since the Indian economy opened up in 1991, Mumbai’s palette has expanded beyond the inevitable pizza joints to savour many more flavours. Thai, with its curry-induced proximity to Indian food, is a favourite, as is Japanese. The arrival of kaya toast, nasi lemak and laksa is but one more step in the city’s unceasing search for newness and experimentation. For Singapore too, it is a welcome move away from “orderly”, “neat” and “clean”—the impoverished, sterile language in which it is usually couched by a besotted sub-continent. Mumbai is a fitting place to right this wrong: another great port city that was plugged into regional trade networks well before colonialism, and whose growth is attributable to its enduring embrace of migrants, modern-day chauvinism notwithstanding.

Even though Lau acknowledged that some ingredients, like shrimp paste, can be difficult to source locally, reviews on Zomato, one of India’s largest restaurant review and food delivery platforms, have been encouraging. Mumbai’s F&B industry, like Singapore’s, is cut-throat, so Lau will be hoping this is a sign of things to come. As will the smattering of Singaporeans who reside in the city. In Hindi, “makan” means “house”. Finally, they have a place that reminds them of the taste of home.

History weekly by Faris Joraimi

“No company—no matter how large or influential—is above the law,” said US Attorney-General Merrick Garland, about the historic ruling by a federal court declaring Google a monopoly in online search, which acted illegally to eliminate competition. While it’s significant that Google may face an existential threat, such state intervention happens fairly regularly (perhaps not often enough): large corporations are regulated or broken up by “antitrust” laws designed to promote competition and prevent market dominance.

It wasn’t always that way. Only in the last three centuries have private firms been able to grow so powerful as to pose a threat to sovereign governments. The British East India Company (EIC)—key to the founding of modern Singapore, as we know—was among the first of such “evil corporations”. In 1600, it was given a trading monopoly for all waters east of the Cape of Good Hope, and permission to raise armies, wage war, and make treaties with foreign rulers. By the following century, this band of uncouth English traders had the strength to defeat the fabulously wealthy and cultured Mughal empire in 1757, and in the words of historian William Dalrymple, force India into “an act of involuntary privatisation”. Cheap, machine-made English textiles wiped out demand for hand-loomed Indian textiles: once the backbone of the Mughal economy. After plundering India’s richest provinces, the EIC went into debt, despite having paid its executives handsome dividends, prompting Parliament to take action. Its 1773 report warned that the EIC would bring the state “down into an unfathomable abyss” and that “this cursed Company would, at last, like a viper, be the destruction of the country which fostered it at its bosom.” While the Crown continued to restrict the EIC’s powers over successive Acts, it took the 1857 Indian Rebellion for the Crown to finally dissolve the EIC and take over its functions.

Monopoly’s bloody history reminds us how much colonialism is rooted in unregulated greed. It’s bewildering to think how companies used to be able to act like governments, but is today’s situation much better? Tech titans seek to monopolise and control our attention, data, and informational channels the way the EIC did land and other traditional factors of production. (Today’s founders, unironically, also cherish a “land grab” growth strategy.) Many wield economic power on par with states: the annual revenue of Alphabet, Google’s parent, is bigger than the GDP of countries as varied as Greece, New Zealand, and Qatar. Their “armies” include highly-paid lawyers and lobbyists and their “weapons” include the threat of tax arbitrage and the lure of jobs and investment. Many masquerade as forums for free expression and debate, while influencing the outcome of elections and censoring activism. Yet we can’t live without them, the vipers in our pockets.

Arts: Casual Poets Society

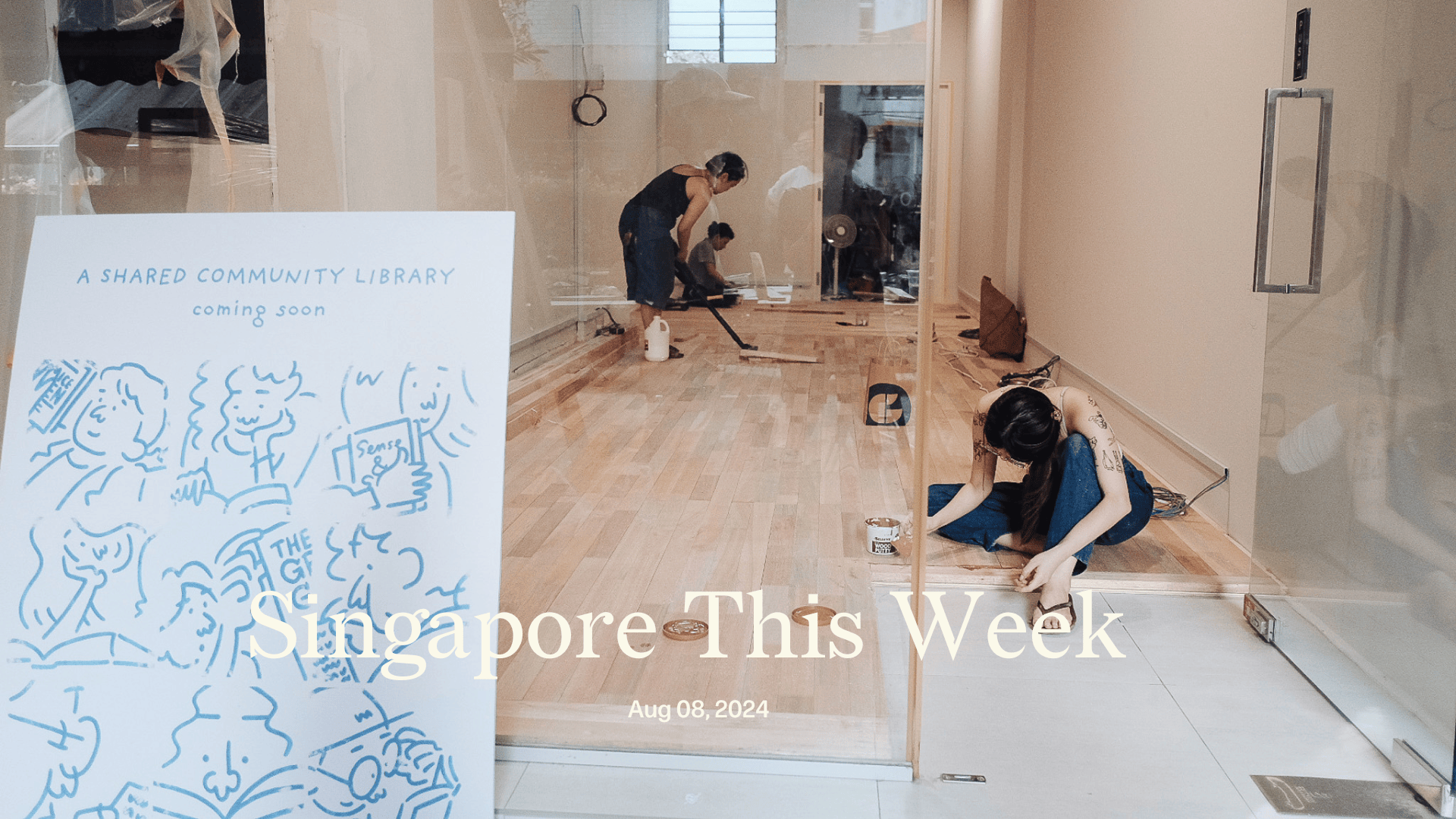

Between an old-school furniture store and a new-school cafe sits the Casual Poet Library, a new community-funded library in the heart of Bukit Merah. The cosy space, which opened to the public earlier this week, is the brainchild of Singaporean photographer Rebecca Toh. While travelling along Japan’s south coast in April, the freelancer happened upon Minna no Toshokan Sankaku, or “everyone’s library”, in the tiny fishing town of Yaizu. Toh was inspired by the community library with a custodianship twist: every shelf is rented by someone who pays a small monthly fee to curate a selection of books for others to browse and borrow, and everyone helps to run the space together. She told CNA: “Who are these people? They’re so impractical—and I love it. I would totally do it.” And she did. The “pragmatic dreamer” took to Instagram in May to send out feelers: would people be willing to pay for a shelf if she opened a similar library here? The answer was a resounding yes. Toh promptly signed a two-and-a-half-year lease for a void deck space in Alexandra Village: “I specifically wanted a void deck. And I wanted to do it in a neighbourhood estate, like where people can walk down from their house and go in, and maybe they can sit outside.”

All of the Casual Poet Library’s 180 shelves, which start at S$49 a month for a six-month lease, have been rented out. Prospective shelf owners will need to join a waiting list. Over 200 people have also volunteered to library-sit. Browsing is free, but you can pay an annual fee of S$25 to borrow up to five books per visit. With all of this ground-up financial input, Toh’s managed to cover the cost of the rent, renovation, utilities and even a bit of remuneration for part-time administrative work. She told FEMALE Singapore that shelf decor and personal notes are encouraged as a way for loaners to connect with borrowers. Shelf owner Nur Amirah, an educator, was thrilled by this: “...whenever I borrow books from the national library, I wish I knew who had this book before I did and what they think of this book. And if you like this book and I like this book, maybe I would like all the other books that you read…But how do I find you?” Pop into the library to find out.

Arts: Greening Singapore’s stages

We often think of theatre stages as fixed, fancy structures: air-conditioned indoor spaces meant for bougie crowds with money to spend and time to kill. But what if you could create a flexible stage that was part theatre, part garden—and part edible? This is “The Living Stage”, a travelling concept initiated by Tanja Beer, an Australian artist-scholar. “We grow the stage with the local community, invite them to perform, and then we eat the stage,” she told a rapt audience of artists and administrators at the Esplanade Annexe Studio earlier this week. (She also refers to herself as an ecoscenographer, a term she coined as part of her doctoral research.) Beer was in Singapore for Green Stages, a new symposium on sustainable theatre by The Theatre Practice, the company founded by the late Kuo Pao Kun. Beer was joined by local theatre artists Ang Xiao Ting and Kok Heng Leun, who discussed making artwork in the throes of a climate crisis, and what they’d learnt along the way: how to encourage the multi-use of materials in a single-use society, nurture informal borrowing systems, curb food waste, or confront assumptions around the “inconveniences” of ecologically sustainable artmaking. The speakers stressed climate transition over climate doomerism, and thinking of ecological challenges as opportunities rather than constraints. Ang, a multi-hyphenate artist who is long engaged in eco-theatre work, described her own sustainability adventure as “an exercise in constantly being surprised”.

Green Stages has a more ambitious goal: to co-create the Singaporean edition of the Theatre Green Book. This free resource, started in the UK, combines practical expertise gleaned from artists with robust methodologies from sustainability experts, and is meant to support best practices in sustainable artmaking, including measuring the path to “net zero”. The Theatre Practice invites those interested in contributing to fill up this form. Even if “net zero” remains a stretch goal for most artists and arts groups, many are putting the environment at the centre of their programming, or playing the provocateur when it comes to getting the public to think more deeply about these issues. Checkpoint Theatre’s upcoming “Playing With Fire”, for instance, interrogates Singapore’s industrial past and present, and the complicated connections between a young writer and a petrochemical company whose employees she’s interviewing. Cheyenne Alexandria Phillips, the playwright, told The Straits Times: “My responsibility is not to provide a solution, it’s to provide a voice for the people who have not yet had a voice in the conversation.”

Tech: How will SG Growth Capital grow Singapore’s start-up ecosystem?

Singapore’s start-up ecosystem has historically benefited from government funding, especially in nascent industries. . Leading this effort has been SEEDS Capital, the investment arm of local economic development agency Enterprise Singapore. Since 2017, SEEDS Capital has ploughed over S$220 million into 160 companies including Homage, a platform connecting caregivers with the elderly, and Ion Mobility, an electric bike company. It has also catalysed more than S$950 million of private sector investments. Separately, since 1991, the Economic Development Board Investments (EDBI) has been investing in foreign companies that have the potential to be vital for Singapore’s economy. The development of the biomedical sector here, for example, is the result of such efforts.

Now, the two are to be merged to form SG Growth Capital, a new public entity. The merger could generate deeper expertise, better sharing of resources and networks to bolster local innovation and fortify Singapore’s position as a global economic powerhouse.

While senior leadership from both EDB and Enterprise Singapore are represented in SG Growth Capital, the chairman and CEO of the new entity will be EDB officers, suggesting that the fund’s focus will be more global than local. This could mean investing in and bringing more global companies into Singapore, and even a reduced focus on local tech enterprises. That would be a pity. Already, funding for early stage deep tech ventures here is limited, especially with venture builder Entrepreneur First pulling out due partly to the local tech talent pool not being deep enough. For Singapore to make the next leap in its start-up ecosystem, it must not only attract the best foreign companies but also grow a stable of global companies from within.

If you enjoy Jom’s work, do get a paid subscription today to support independent journalism in Singapore.