Cost of living and housing are by far the most pressing political issues for Singaporeans, far outstripping concerns like immigration, working conditions, and race relations. There is some variation within age and racial groups—Gen Zs and Malays, for instance, are relatively more concerned than other ages and races, respectively, about Israel and Palestine. But even for them, the general emphasis on prosaic concerns holds true.

This is one of the key findings from Jom’s first-ever voter sentiment survey, of 1,000 citizens aged 21 and over, which we commissioned Milieu to conduct in June this year. (Our full methodology note is at the end.) Like any survey, findings should be taken with a pinch of salt. Various forms of bias can together cause a divergence between the results we observe and the shared reality we pine for.

Their flaws notwithstanding, such surveys are essential guides to our civic and political lives. What does your fellow Singaporean, part of your imagined community, think about life here? Sadly, they’ve hitherto been lacking in our nascent democracy. When surveys are conducted, usually by government-controlled or -funded institutions, there’s insufficient transparency. In the interest of openness, Jom will also publish the raw data that Milieu sent us, when we publish the second of this two-parter next week. Play with it; tell us what we’ve missed.

We crafted, among others, four barometer-type questions: satisfaction with life overall; satisfaction with the government; perception of economic conditions; and perception of personal financial situation. While the findings are interesting in their own right, their salience will improve over repeated surveys, as we observe the shifts in sentiment.

The usual establishment surveys, meanwhile, also shy away from supposedly sensitive questions, including perceptions of leaders. What are the approval ratings of Lee Hsien Loong, former prime minister? Are voters confident in Lawrence Wong’s ability to deliver as new prime minister? How likeable is Pritam Singh, leader of the Opposition?

We’ll share those insights next week, in “Singapore’s most popular politicians”. Today, we’ll examine Singaporeans’ political interests and imperatives.

Respondents were asked to choose as many pressing political issues as they wished, from a fixed list. A whopping 76.9 percent cited cost of living, and 53 percent also said housing. Those two issues, which are of course related, are the only ones mentioned by a majority of Singaporeans surveyed. Even immigration, which can sometimes feel like a tinderbox, is of concern to only slightly over a quarter of Singaporeans. Israel-Palestine (16.7 percent), race relations (16.6 percent) and issues faced by the LGBTQ community (13.2 percent) are the least pressing political issues.

An open-ended question allowed respondents to suggest other issues. Here, there was some vitriol towards foreign workers. There were also some novel issues mentioned, including “mental health”, “work-life balance and animal rights”, and “three wheels PMD out of control, very unsafe while walking everywhere.” Still, about a quarter of the 27 comments further articulated concerns with socioeconomic issues.

In the barometer question on personal financial situation, only 28 percent of respondents said they are “Able to live comfortably” here. Others chose “Needs are met with a little leftover” (37.2 percent), “Basic expenses just about met” (28.5 percent) or “Basic expenses not met” (6.4 percent). A pessimistic takeaway might be that many Singaporeans appear to be struggling to get by—particularly given that 6.4 percent of respondents don’t even earn enough for basic expenses. An optimistic one, by contrast, would be that some two-thirds of Singaporeans say their needs are more than met—not unlike the 64 percent of Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) respondents who say that their “Income covers living expenses”.

This is perhaps the interpretation that will be proffered by the establishment. For years, the ruling People’s Action Party (PAP) has been on two cost-related narrative counter-offensives. First, arguing that prices here actually aren’t that bad—international cost of living surveys mostly represent the expat crowd, apparently—and that lower-income Singaporeans can get by with the help of subsidies and handouts. Second, defending hikes in the goods and services tax (GST) as fiscally sound, while criticising the Opposition for its apparent lack of long-term prudence. (The Opposition has been wanting to defer GST hikes and/or dip more into the reserves, in order to bolster support for the less fortunate.)

We can expect these debates to dominate the next general election (GE), due by November 2025. Many analysts now believe that Lawrence Wong, prime minister, will call it sometime after Budget 2025—soon after he, also minister for finance, has doled out goodies to ameliorate those very cost-of-living pressures.

Same old election ploy, one might argue. Though the stakes this time seem greater.

Some further reading:

“Affordability in the lion city: is Singapore’s public housing model built to last?” by Jonathan Lin

“Power to the people: Labour Day Rally 2023” by Jom

Compared to other age groups, Gen Zs are more likely to be concerned about inequality, freedom of the press, race relations, issues faced by the LGBTQ community, and the Israel-Palestine conflict. Given that cost of living and housing are still the most important to them, it may be tempting to dismiss these other democratic and socio-cultural issues.

Still, if one considers how youth activism on Gaza-related issues—including the unfurling of an “End SG-Israel Arms trade” banner in Gardens by the Bay—has caught the government off guard over the past year, that may not be wise. Nearly one in three Gen Zs consider Israel-Palestine a pressing political issue for Singapore. It’ll be interesting to see if any Opposition parties prioritise the reshaping of foreign relations, even if just with Israel, in their manifesto.

The 45-54 age group, by contrast, appears to be the most concerned about all the aforementioned bread-and-butter issues. They’re also the least satisfied with life overall; the government; economic conditions; and their own financial situation. Those of them in the so-called “sandwich class”, with many dependents, could potentially be living with the most financial precarity.

Some further reading:

“Genocide in Gaza? Our moral responsibility” by Jom

“The Singapore Dream fades for the ‘sandwich class’” by Reeta Raman

It’s important to preface this discussion by asserting that we don’t necessarily agree with the ways in which the colonial-era Chinese-Malay-Indian-Others (CMIO) classification is deployed in Singaporean society. Still, it is what we must work with for now.

Among the few clear differences is that Chinese are relatively less concerned about race relations (11.9 percent), with Others the most so (50.8 percent). Indians (34.4 percent) and Malays (23.4 percent) are in between. Many Chinese are only now waking up to the concept of racial privilege. In recent decades, the myth of a multiracial paradise has been relentlessly punctured by stories of non-Chinese experiencing numerous forms of discrimination, including casual and structural racism. For Indians and Others, it’s also often conflated with xenophobia into a toxic mix—the “CECA Indian” trope for the former—which perhaps explains their greater levels of concern.

There’s a similar racial trend with “working conditions”, and the two points are possibly related. Numerous surveys speak to the ethnic discrimination that benefits Chinese in the workplace and elsewhere.

Indians and Others are seemingly more concerned about issues faced by the LGBTQ community than are Chinese and Malays. One possible reason is that conservative Abrahamic religions may have more of an influence on the latter two groups’ views on gender and sexuality.

Are Singaporeans apathetic? The debate will rage on, but at least amongst our respondent base, there is clear interest in politics across educational levels. A majority of every group is either “Very interested” or “Somewhat interested” in news about politics and government. Among respondents with at least a university degree, over three-quarters expressed such interest.

Only 26 percent of voters overall are “Very certain” about their choice of party at the next GE. Indians generally appear to be more certain than the other groups.

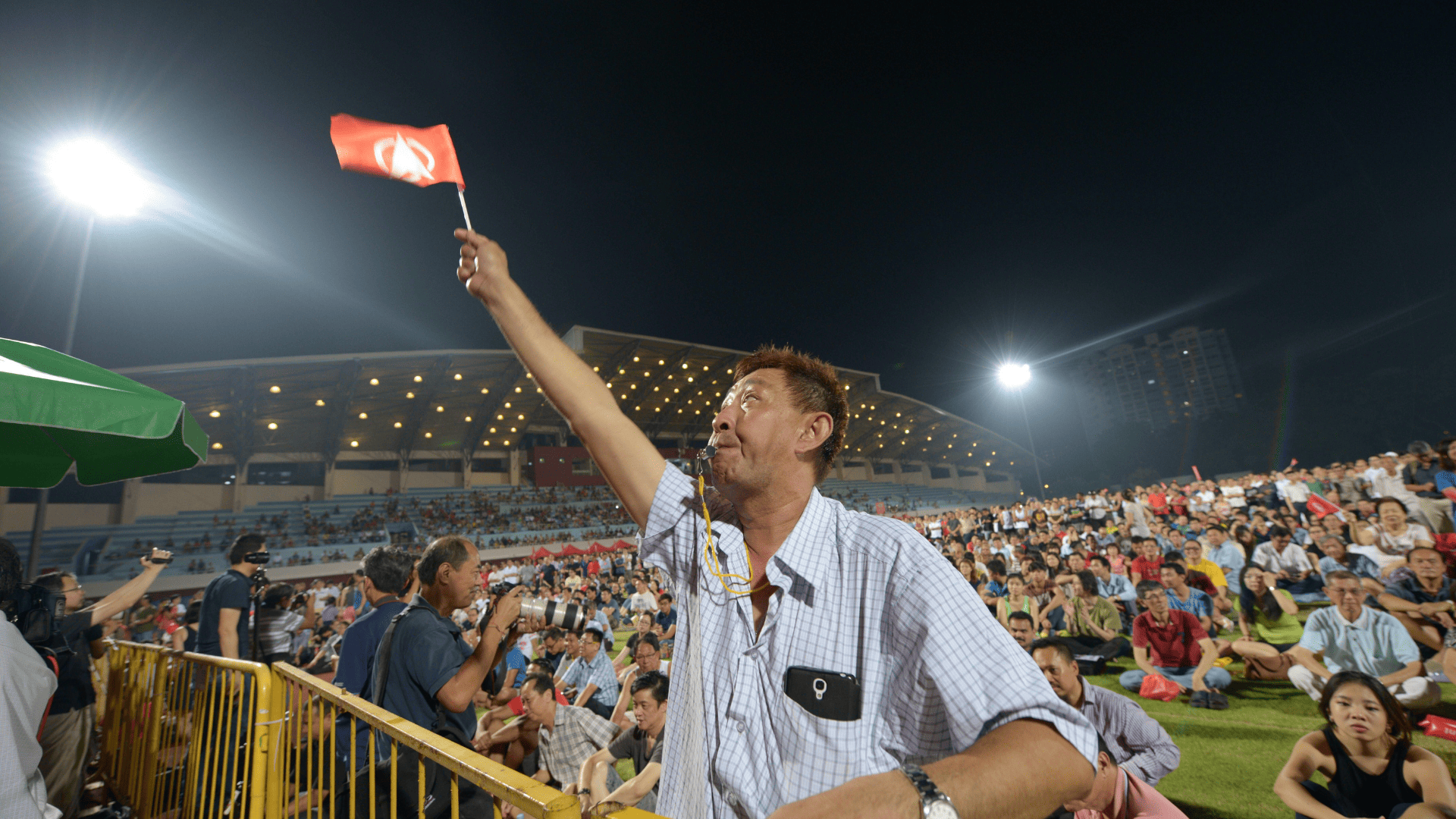

One of the clearest correlations in the survey is between age and certainty of vote. The older a Singaporean is, the more certain they appear to be about their choice of party at the next GE. To be sure, it’s a fairly common trend in democracies around the world: the unpredictability of the youth vote and the loyalty (inertia?) that can develop with age. It’s also perhaps why the PAP has steadfastly refused to lower the minimum voting age. At 21, Singapore is in a rarefied club globally. (In 2019, Malaysia lowered it to 18, as is common in many democracies.)

Ahead of the next GE, this age-certainty correlation suggests that political parties should dedicate relatively more resources towards attracting the youth vote. They’ll probably need more than goofy TikToks.

This chart dissects certainty of vote by political affiliation. Just over 40 percent of PAP supporters are “Very certain” of their vote, compared with 55 percent of Opposition voters. Among non-partisan Singaporeans, meanwhile, only 13.4 percent are.

Political analysts generally assume that the swing voter segment in Singapore is around 35-40 percent of the electorate, bigger than in most democracies. Among other assumptions that feed this: the 35 odd percent who voted for Tony Tan, the PAP candidate, in the four-way 2011 presidential election are assumed to be PAP diehards; and the 30 odd percent that did not vote for Tharman Shanmugaratnam, the PAP candidate, in last year’s three-way presidential election are assumed to be “anything but PAP”.

In a fireside chat with Jom earlier this year, Leon Perera, former member of Parliament with the Workers’ Party, suggested that there are four different types of swing voters in Singapore: PAP default, Oppo default, a segment that is more transactional, and one that is less politically invested.

Though they’re related, it’s not clear how exactly the swing voter analysis and depictions match onto the responses to this question. What seems quite apparent is that many Singaporean voters, including those who identify as PAP or Opposition supporters, will be heading into the next GE with fairly open minds.

That’s what the survey ostensibly says. But this is one of those questions for which we must consider potential survey biases. In July, when Jom first presented these results at a media fair organised by the Network of Independent Media for Better Understanding & Support (NIMBUS), Walid Jumblatt Bin Abdullah, an associate professor at Nanyang Technological University (NTU), cautioned us about the social desirability bias and personal desirability bias that are sometimes expressed in survey respondents’ answers.

For the former, what Walid also called the “shy Trump voter” phenomenon, respondents may be unwilling to signal their real preferences, even in an anonymous survey. For the latter, it’s a question of honesty with oneself. “They don’t want to think that their votes are actually fixed,” said Walid. “They want to think that they are more malleable and more liberal than they actually are.” All this may explain why so many voters are still seemingly undecided.

Here is one of the four barometer questions that we’ve asked in this base year. A clear majority of Singaporeans are at least “Somewhat satisfied” with the performance of the government.

There are some notable variations by age group. A relatively high proportion of young people (16.6 percent) are “Very satisfied”, which should assuage some PAP concerns about the aforementioned unpredictability of the youth vote. The only other demographic with more enthusiasm is those 55 and over (19 percent). The party might worry, however, about those aged 45-54, as suggested earlier. Just 9 percent of them are “Very satisfied” and a startling 10 percent of them are “Very dissatisfied”.

Which politicians are most likely to be able to appeal to disgruntled Singaporeans? We’ll tell you next week.

Methodology note

Our team was eager to craft a survey that could capture how Singaporeans felt about a range of important political and socio-economic issues. We assessed similar surveys overseas, including those conducted by Gallup and Pew, before deciding on the final list of questions, in consultation with Milieu.

This is what led to our combination of barometer questions, which will over time indicate how sentiment is shifting in Singapore; questions about issues of concern, in which we also provided an open-ended answer box, so as not to nudge respondents towards our own biases; questions about voting behaviour; leadership approval and politician likeability questions (see next week’s piece); and a one-off, topical question assessing what Singaporeans think of politicians’ extramarital affairs (next week too).

When it conducted its fieldwork, surveying Singapore citizens 21 and above, Milieu set hard quotas for age, gender and ethnicity while setting soft quotas—which are more flexible and serve as guidelines—for income and education. These quotas are meant to approximate each segment’s representation in broader society.

After completing its fieldwork, Milieu weighted the data: a statistical technique used in market research to adjust the contribution of different segments of the sample to ensure that the overall composition accurately reflects the target population’s characteristics. In the majority of cases, including this one, weighting the data does not significantly change results.

Jom’s expanded voter sentiment survey team included the following contributors: Pradeep Krishnan, Loh Pei Ying, and Robin Vochelet. We’re grateful for their help over many months.

Letters in response to this analysis can be sent to sudhir@jom.media. All will be considered for publication on our “Letters to the editor” page.

If you enjoy Jom’s work, do get a paid subscription today to support independent journalism in Singapore.