Incorruptibility is a bedrock principle upon which Singapore is built. We have every reason to be proud of this legacy. Inevitably, there are going to be times in our national life when circumstances will test our commitment to this foundational value. But such times also offer an important opportunity to strengthen our system. This is one of those seasons.

Over the past few months, several matters have caused some unease among Singaporeans. These include senior Keppel executives being given stern warnings in lieu of prosecution for their involvement in a massive, decade-long bribery scheme in Brazil; and the decision by Tin Pei Ling, a member of parliament (MP) with the ruling People’s Action Party (PAP), to accept a senior public affairs and policy role with Grab, while simultaneously being chairperson of a seemingly associated Government Parliamentary Committee. Tin later gave up that role after significant public disquiet.

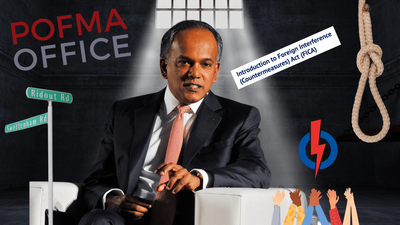

Most recently came news that Home Affairs and Law Minister K Shanmugam and Foreign Affairs Minister Vivian Balakrishnan had leased bungalows on Ridout Road from the Singapore Land Authority (SLA), a government statutory board falling under the former’s oversight. Three days ago, Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong announced that a review into this matter will be conducted by Senior Minister (SM) Teo Chee Hean (who’s also Coordinating Minister for National Security).

How should we properly assess this subject and the government’s planned review? Let’s start with some general observations.

Clearly, the optics of a minister entering a transaction with an agency under his oversight are less than favourable. It has, however, been suggested by some that where a rental or other similar opportunity is open to the world at large, there can be no serious objection with cabinet ministers (or their family members) participating in their capacity as private citizens. The matter needs to be approached with some nuance.

First, a Ministerial Code of Conduct has been promulgated to avoid actual or apparent conflicts of interests. Absent an independent agency or formal mechanism through which any potential conflict of interest by a minister has to be cleared, there is a good argument to be made that there must be scrupulous observance of the Code. It’s not even a matter of actual wrongdoing—as long as a transaction involving a minister can create the perception of special treatment, it must be avoided.

Second, even if it is felt that that is too strict a position, any government transactions involving ministers (or their family members) must be subject to important caveats: there must be robust processes in place to deal with any actual or apparent conflicts of interest, and these must be scrupulously observed; full and frank disclosure is made that the counterparty is a minister (or their family member); there is no misuse of confidential, non-public information; the minister receives no favourable treatment; the government agency reaches its decision independently and impartially; and the resulting transaction is done on objectively verifiable and fair commercial terms. The safeguard cannot merely involve notification to a senior cabinet colleague. It needs to be much more robust and transparent.

Third, given the realities of modern life and the expansive reach of the government and government-linked companies in practically every aspect of Singaporean life, we can expect there to be yet more instances of dealings between ministers and MPs (and members of their families) with government agencies and regulators, whether in relation to business, appointments, jobs, licences, or approvals. However robust our processes for addressing possible conflicts of interest in such dealings, delicate and perhaps even blunt, uncomfortable questions will inevitably arise. We must embrace, not disparage, such questions.

The questions, and proper responses to them, are essential in demonstrating our commitment to ensuring that any arrangements involving senior government officials (or their family members) are completely above board. Probing questions also provide us with a valuable opportunity to consider whether existing safeguards and practices are good enough. At heart, when Singaporeans ask uncomfortable questions, it is because we care for our country and wish to see it grow stronger.

As I wrote in my recent commentary on the Keppel bribery scandal: “...[d]oubts which strike at the foundation of our commitment to incorruptibility and the rule of law must never be allowed to take root.” It is the responsibility of every concerned citizen to press the necessary questions, and for the government to rigorously and fairly attend to them to dispel even the slightest perception of anything less than fair play or transparent dealings.

With these observations in mind, the ultimate credibility and effectiveness of the government’s review into the Ridout Road leases will turn on two points.

First, full disclosure of all material facts. Suffice to say, the review should cover the following:

- What processes the government has in place to deal with any actual or apparent conflicts of interest and how they were followed in this case;

- What were the reason(s) the Minister for Home Affairs and Law submitted his bid via an agent and did the SLA know that the minister was the ultimate principal behind the bid? If so, how, and when did the SLA come to know this? If not, how was the SLA to effectively abide by any protocols to avoid possible conflicts of interest without this information?;

- Did the SLA take independent advice from the Attorney General’s Chambers on the processes it should put in place to ensure a level playing field existed and to address any possible conflicts of interest? If not, what steps did the SLA take to properly address this?;

- Apart from not disclosing the guide rent, what steps did the SLA take to ensure that the ministers were not in any advantageous position over the world at large in relation to the rentals of both bungalows?;

- What is the recent history of the tenancies of both properties and under what circumstances did the previous tenants come to leave each property?;

- Why did both properties remain vacant for such an extended period before the leases to the ministers were granted? What steps did the SLA take to rent out the properties in that time?;

- The full costs of the renovations to each property and who bore them;

- The period for which each property was advertised and whether that period was adequate to secure properly competitive bids;

- The rent payable for each property, how that was derived and how it compares with market rent;

- The lease renewal terms for each property; and

- Were there any non-standard tenancy terms negotiated with either minister and, if so, what were those terms?

Ideally, the review should also disclose copies of both tenancy agreements, as well as all key written communications between the SLA and the ministers (or their agents) leading up to the entry and renewals of the leases, including the renovations. The Singaporean public appreciates the issues, and knows when the government’s responses are fair, in as much as it knows when there are shortcomings. The more detailed, thorough and wide-ranging the review report, the greater its ultimate credibility.

Second, the perceived independence of the review. There is nothing more powerful to address concerns of possible conflicts of interest than oversight or review by a respected, independent, external third party who is given full access and who then reports the findings publicly.

This is where the planned review will face some challenges.

To give credit where it is due, the May 24th statement from the Prime Minister’s Office records that both the affected ministers had requested “a review that is independent of the ministries and agencies they supervise”. The government has also appointed SM Teo, one of the most senior cabinet ministers, to lead the review. There is no question of SM Teo’s seniority and standing and the fact that he is independent of the relevant ministries and agencies involved in this case.

At the same time, SM Teo is from the same party as the two ministers, and is also their cabinet colleague, in the same executive branch of government. Given this, and the importance and political sensitivity of the matter under review, it is not unreasonable for an objective observer to take the view that there ought to be a greater degree of separation between the individual heading this review and the ministers involved. Here, there would have been much to commend the appointment of any of our Supreme Court judges, current or retired, to lead this review. It is still early enough in the review process for the government to adjust course and do so.

Singapore’s national culture of incorruptibility is a precious legacy we have inherited. It needs to be carefully nurtured and preserved by each successive generation. Uncomfortable as questions or commentaries may be about the Ridout Road leases, they present us an opportunity to reinforce our commitment to this core national value.

Harpreet Singh Nehal is a Senior Counsel. A graduate of National University of Singapore, Harvard Law School and a former Justices’ Law Clerk, he was previously a partner of Drew & Napier and later of the UK Magic Circle law firm, Clifford Chance. In 2019, he established his own boutique litigation firm, Audent Chambers, where he is managing partner. He is also a member of Harvard Law School’s Leadership Council of Asia.

If you enjoy Jom’s work, do get a paid subscription today to support independent journalism in Singapore.

Letters in response to this piece can be sent to sudhir@jom.media. All will be considered for publication on our “Letters to the editor” page.