The world still lives with the scars of the 20th century’s Communist conflicts. On the one side, totalitarian dictatorships, led by the likes of Stalin, Mao and Pol Pot, killed their own people, through purges of landowners and other enemies, agrarian and industrial dystopias, and various forms of wilful neglect. They inspired and supported insurgencies around the world, as a romantic theology of liberation and equality mesmerised millions living for centuries under the thumbs of aristocrats and colonialists. In its seductiveness lay its capacity for violence. (More enlightened expressions of Communism, such as in the state of Kerala, India, would forever be overshadowed by the ideology’s excesses.)

On the other side, driven by an intense paranoia about a red wave crashing across their lands, numerous centre- and right-wing governments, from Argentina to Taiwan, arrested, detained, tortured, “disappeared” and massacred suspected communists. Many anti-Communist regimes were covertly supported by the US, itself in the throes of a post-war, global capitalist dogma. They displayed a wanton disregard for facts, for the reality of any individual’s convictions. Socialists and other peaceful thinkers were caught up in this dragnet, transformed by association, alongside genuine threats, into enemies of the state. In the decolonising world, many who were merely anti-colonial were branded “communist”.

The sheer arbitrariness of it all is evident from documentaries like “The Act of Killing” (2012), which exposed, in semi-fictional farce, the bloodthirsty rampage unleashed by Suharto’s junta, with tacit support from the CIA, as it slaughtered some half a million Indonesians; and “Nostalgia for the Light” (2010), which blends astronomy and archaeology into an exploration of memory, family and loss, several decades after Pinochet, another US-backed general, sent Chilean leftists to gulags in the Atacama. From the humid, sea-level tropics to dry, high-altitude deserts, the world still lives with the scars.

But not Singapore. Our exceptional country was spared the atrocities of this global, anti-Communist purge. While politicians everywhere succumbed to the “Red Scare”, our unimpeachable Mister Lee Kuan Yew did not. In his infinite wisdom, Lee cracked down only on actual Communists and their supporters who posed a violent security threat to Singapore.

This is the story that the ruling People’s Action Party (PAP) would like us to believe. Every year there are more reasons to doubt it.

We know that from 1959 to 1990, Lee’s government arrested and jailed without trial over a thousand people in Singapore. Chia Thye Poh, arrested in 1966 and fully released only in 1998, is considered one of the world’s longest-ever prisoners of conscience. Singapore neither gave detainees their day in court, nor has it ever shared any concrete evidence to substantiate these claims.

Conversely, over the past decade Dr Poh Soo Kai, founding member of the PAP, whom Lee jailed in 1963’s Operation Coldstore, and a number of Singaporean researchers and historians such as Hong Lysa and PJ Thum, have unearthed newly-declassified documents in the UK that cast even more doubt on Lee’s actions and motives.

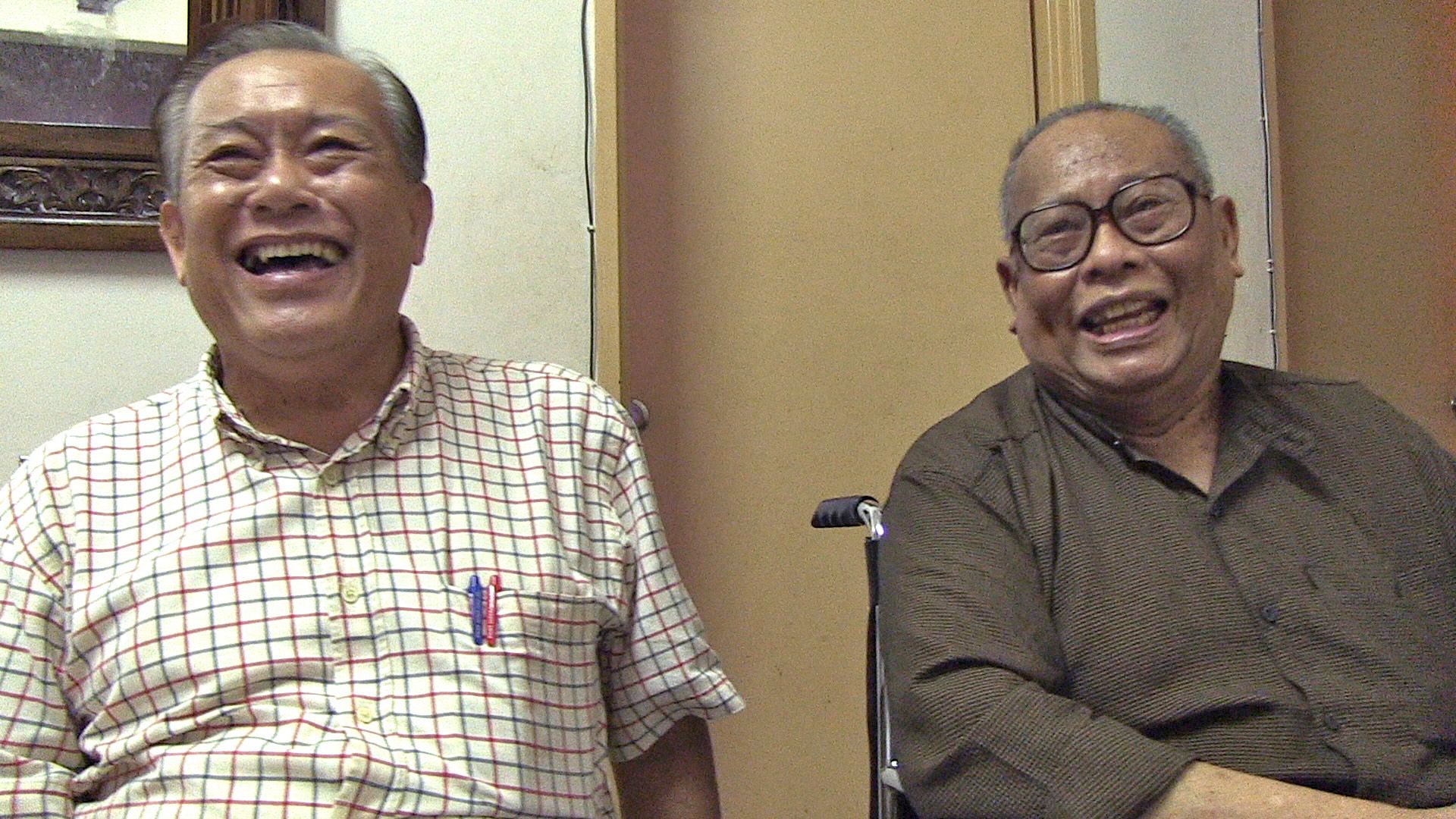

Yesterday, on the 60th anniversary of Coldstore (Feb 2nd 1963), the 91-year-old Poh, sprightly as ever from his current home in Seremban, Malaysia, issued a statement of demands on behalf of many imprisoned without trial under the notorious Internal Security Act (ISA): calling for the abolition of the ISA, and asking for an apology and compensation from the PAP government. This comes in the wake of Joko Widodo, Indonesia’s current president, expressing “strong regret” for the “gross human rights violations” that have occurred in that country.

It’s important that we give Poh, a key player in Singapore’s journey to independence, a fair hearing. Because even if Lee did act in Singapore’s best interests, and even if he was responding to a genuine fear of being overthrown by a violent insurgency, it’s entirely possible that he overreacted, causing different arms of the state to inflict torture and other grave injustices on our fellow Singaporeans.

If true, then 1963’s Coldstore was Lee’s “original sin” (as Hong puts it), the one that emboldened him, that convinced him that the path to hegemony required extra-judicial manoeuvres—ones he could get away with.

In the early hours of February 2nd 1963, just as Muslims were beginning to rise on the eighth day of the holy month of Ramadan, and when Hokkiens were heading to bed after carrying out prayers on the ninth day of the Lunar New Year (拜天公), one of the largest police operations in Singapore’s history was conducted.

Coordinated by the British, Malayan and Singaporean governments, Operation Coldstore saw the detention without trial of over 120 trade unionists, politicians, journalists, teachers and students. This included almost the entire leadership of Barisan Sosialis, the leading opposition party in Singapore. Pictures of those arrested were splashed across newspapers, under frontpage headlines like “Communist conspiracy in Singapore” and “THE BIG RED ☭ PLOT.” “The Reds,” as many of these men and women had been called, were said to have planned for “violent agitation” and “a period of bloodshed and disorder.”

But whether such plans ever existed has been a point of contention for six decades now. Singapore’s establishment maintains that Coldstore was a “security operation”, but former political detainees and a growing number of historians have argued that, on the contrary, it was politically motivated, hatched to destroy all legitimate opposition in Singapore. The orthodox narrative is a bifurcated tale, coloured by the violent red communists on the one side and the (PAP’s) peaceful men in white on other. It allows little room for nuance, let alone debate.

But we must approach this issue expecting complexity. The period from the mid-1950s to 1963 was a politically turbulent one, marked by loose and shifting allegiances among Singaporean leaders, as they sought to establish power bases among a body politic steeped in anti-colonial and leftist rhetoric. All while managing relations with a newly-independent Malaya, and navigating external and internal risks, from fluctuations in rubber prices to incipient communal instincts.

These events happened against the backdrop of the slow, grudging withdrawal of the British. Independence occurred in stages. From 1955 to 1959, Singapore enjoyed partial self-government. The PAP and other parties competed in legislative elections. The Federation of Malaya (known as West Malaysia today) achieved full independence in 1957. In 1959, Singapore won full internal self-governance, while the British continued to manage foreign relations and internal security. Singapore’s ill-fated merger with the Federation of Malaysia in 1963—an event inextricably tied to Coldstore—lasted till August 9th 1965, the day it gained independence.

Declassified British records give some idea about the pressures on Lee leading up to Coldstore. It’s worth examining these even while acknowledging that the picture is incomplete—some gaps will be filled only if Singapore’s Internal Security Department (ISD) opens its archives.

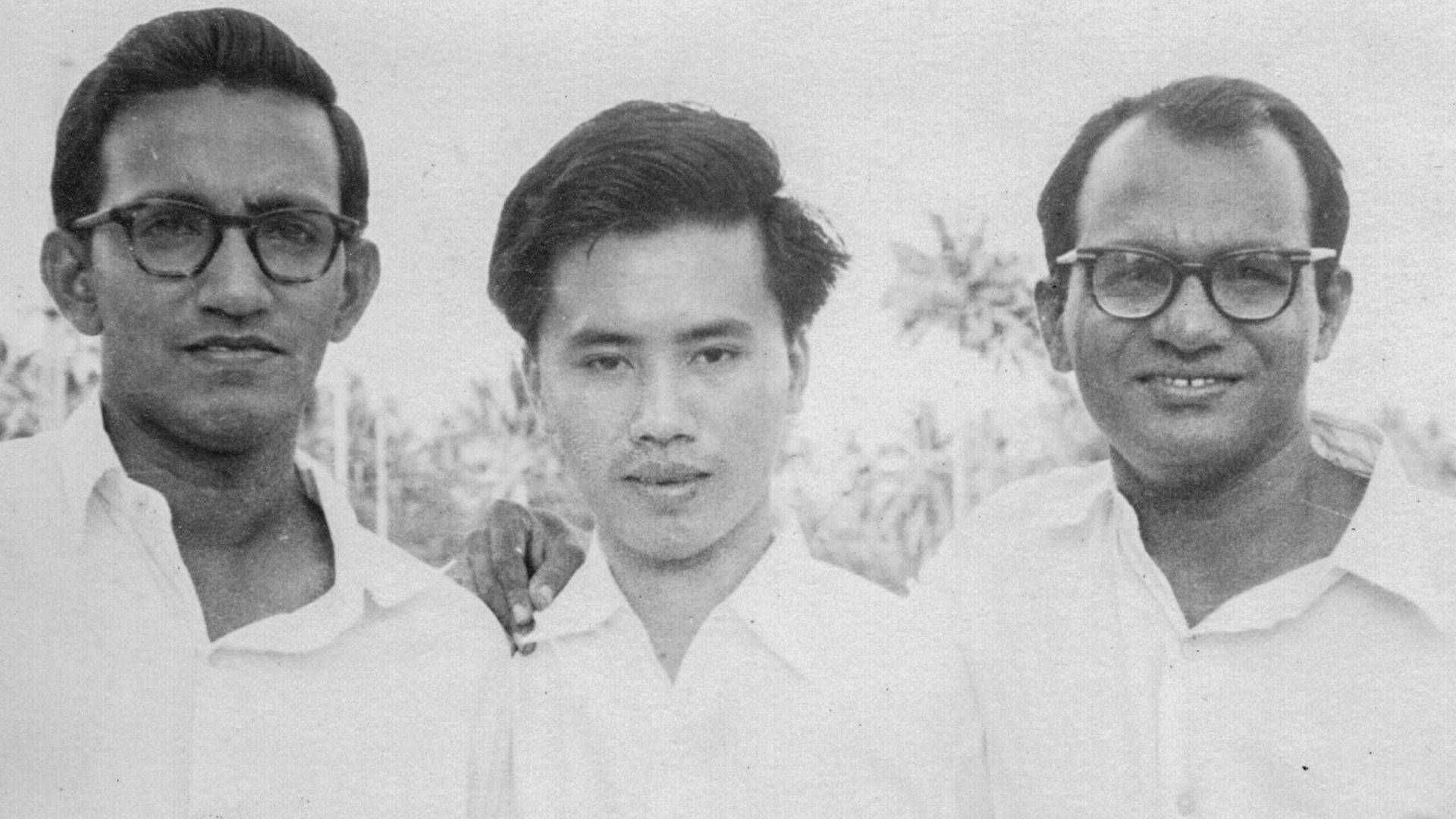

Consider first that many of those who were later labelled “communists” were instrumental in the PAP’s rise. This includes Lim Chin Siong, Fong Swee Suan, S Woodhull and James Puthucheary. When they were detained without trial by the Lim Yew Hock government in 1956, Lee demanded that they “be brought to trial in open court or released unconditionally.” He pledged to “to fight for their democratic rights.” Just before the 1959 General Election, in which the PAP swept to power and Lee became the nation’s first prime minister, he told voters that if his party won the election, it would release all PAP members who had been detained without trial: “We don’t abandon our comrades-in-arms.”

As far as the PAP was concerned—at least publicly—the attempt to call political detainees “communists” was an excuse to curtail democratic rights. The PAP refused to take office until the British released eight of its most senior party members from prison. It was expected that in the subsequent weeks and months, the remaining ones would also be freed. They were not. Declassified British documents indicate that: “Although Lee has publicly demanded release of detainees and attacked [the] detention order under which they are held, he has, in private, recognised that maintenance of detention order is essential.”

The realisation among many left-wing PAP members that Lee was not going to push for the release of the remaining political detainees precipitated a split. Lee’s intransigence was likely in part driven by his worry that businesses would flee Singapore if they believed its leadership was too left-leaning.

The PAP’s waning popularity became clear when its candidate lost a by-election to Ong Eng Guan, its former national development minister, in the Hong Lim constituency in April 1961. Calling for the release of political detainees and the expansion of democratic rights in Singapore, Ong won a thumping 73 percent of the vote.

To the surprise of many, just a few weeks later Tunku Abdul Rahman, the Malayan prime minister, made an about-turn from his previous statements and declared an interest in having Singapore merge with Malaya. In 1977, Tunku wrote in his memoir:

I can reveal now that I only accepted Singapore because of Britain’s unequivocal stand, which was that unless we could take Singapore in they would not relinquish their hold on the island colony…So it is evident I had no choice.

Having pledged that it would work for the independence of Singapore through merger with Malaya, the PAP had been provided by the Tunku—and, indirectly, by the British—a lifeline. Through merger with a bigger entity the PAP, with its back against the ropes, could conceivably consolidate its power internally.

In July 1961, the PAP was faced with another by-election, this time in Anson, against Workers’ Party (WP) chief, David Marshall. Frustrated by the leadership’s failure to consult party members on the fates of political detainees, trade unionists like Lim, Fong and Woodhull withdrew their support from the PAP.

Before voters went to the polls, the editorial of the PAP’s official paper, Petir, stated that Anson was “a Singapore in miniature” and would test whether the Government still had “the moral authority” to rule. After Marshall beat PAP candidate Mahmud Awang, George Douglas-Hamilton, the British commissioner commonly known as Lord Selkirk, met with Lee and Goh Keng Swee. He found them to be “pretty broken men, extremely jumpy and uncertain of their political future.”

A few days after the election, Lee sacked the party’s left-wingers, perhaps confident of his merger gambit. Yet their resurgence must have surprised him. They went on to form Barisan Sosialis, which took with it “35 of the [PAP’s] branch committees, 19 of the 23 organising secretaries, and an estimated 80 percent of the membership.” According to British declassified documents, Barisan were “the strongest political force in Singapore.”

At that stage, merger with Malaya was not expected soon, but in about five to six years. Philip Moore, the deputy British commissioner, recalls a worried Lee:

in order to avoid the Communists taking over, he would create a situation in which the UK Commissioner would be forced to suspend the Constitution. This might be done either by the Singapore Government inviting a Russian trade mission to Singapore thus forcing a constitutional crisis, or by instigating riots and disorder, requiring the intervention of British troops. I did, however, form the impression that he was quite certain he would lose a general election and was seriously toying with the thought of forcing British intervention in order to prevent his political enemies from forming a government.

The rapid rise of Barisan Sosialis probably hastened Singapore’s merger with Malaya. Singapore held an integration referendum in September 1962 (Barisan Sosialis called for blank votes after a boycott was criminalised); Lee carried out Coldstore in February 1963; and Singapore joined the Federation of Malaysia in September 1963.

There are numerous other issues concerning the problematic merger—including the electorally warped referendum options presented to Singaporeans; the Cobbold Commission charged with determining if the people in (present-day) Sabah and Sarawak wanted to join the Federation of Malaysia; and the Brunei Revolt of December 1962 that intensified the “Red Scare” fears among Malayan, Singaporean and British officials—that are tangentially interesting but beyond the scope of this essay.

Just a few months before Operation Coldstore, Selkirk, who sat on the Internal Security Council, wrote a memo to a colleague stating that Lee

is probably very much attracted to the idea of destroying his political opponents. It should be remembered that there is behind all this a very personal aspect...he claims he wishes to put back in detention the very people who were released at his insistence—people who are intimate acquaintances, who have served in his government, and with whom there is a strong sense of political rivalry which transcends ideological differences.

Yet, Lee Kuan Yew was anxious about taking responsibility for the arrests. In another declassified British document from late 1962, we see Lee toying with the idea of:

...resign[ing] as Prime Minister and hand[ing] over to Goh Keng Swee. This would achieve two objects [sic]. First he would be able, as Secretary-General of the P.A.P, to concentrate on recovering the lost ground in the trade union movement, Secondly he would be absolved of any personal responsibility for the arrest!

It is unsurprising then that when asked about Operation Coldstore at Seletar Airport two days after the arrests, Lee told reporters that “if it were an action by the Singapore government, we would never have contemplated it.” Despite the fact that he had been one of the driving forces behind the arrests, he was frightened to take full responsibility for them.

After Singapore merged with the Federation of Malaysia in September 1963, many more arrests followed. Poh wrote in his memoir that “this was the primary reason for [the creation of] Malaysia: so that the Tunku could take responsibility for wielding the Internal Security Act against the left which Lee could not do without alienating a significant segment of his electorate.”

“Was there really a tiger? Did the tiger want to swallow anybody? Or was there a movement with a wide range of political views from extreme left to social democratic right which attempted to create an alternative to a colonially-designed society, an embryo for creating a new Malaya?” asked Dominic Puthucheary, who had been a senior member of Barisan Sosialis, in an interview in the early 2000s.

To try to answer these questions, we need to be clear that there were indeed communists in Singapore in the 1950s and early 60s. But it’s uncertain if they were strong enough to stage an insurrection. In 1959, Singapore’s Special Branch estimated that the strength of the Malayan Communist Party in Singapore was low: “40 full party members, 80 ABL [Anti-British League] cadres; 200 or so ‘sympathisers’ and less than 100’ ‘released’ for ‘White Area work.’”

There’s also no evidence that Barisan Sosialis had any formal dealings with the MCP. “Contrary to the countless allegations made over the years by Singapore leaders, academics and the Western press, we never controlled the Barisan Socialis,” said Chin Peng, the MCP’s leader, in his memoirs.

Lim Chin Siong, the leader of Barisan Sosialis, did have multiple meetings with “the Plen”, otherwise known as Fong Chong Pik, the MCP’s representative in Singapore. But so too, on several occasions, did Lee. According to Chin Peng, Lee himself had approached MCP members in 1954 “to send cadres to help him” establish a new political party. People like Devan Nair and Samad Ismail, who Lee knew were card-carrying communists, were asked to be the convenors of the party in November that year. Lee had also sent Samad to the historic Afro-Asian Bandung conference in 1955 to represent the People’s Action Party.

The historian Kumar Ramakrishna, one of the few academics given access to the ISD archives, has cited discussions of armed struggle that took place in Barisan meetings. But it’s important to note the conclusions of these meetings: that the constitutional method should continue to be followed, as it was still open to the people.

If discussions on armed struggle alone were evidence of being a communist, then people like Lee and Goh Keng Swee could just as easily have been branded “Red”. When Goh was a student in London, he had an argument with a British man about the use of violence. Goh told him “Look, if every other form of constitutional process has failed and if you cannot get your independence by peaceful struggle, by peaceful constitutional methods, then if you have to use force and resort to an armed rebellion, I say, I will support it in principle.”

Similarly, in April 1961, Lee explained: “There may be circumstances when violence becomes necessary but only when all avenues for peaceful change have been closed to the people.” For these reasons, Lee endorsed violence in certain anti-colonial contexts like Indonesia, Vietnam, Algeria and South Africa.

So too did Lim. But he maintained, even after being imprisoned, that the constitutional path was still available to the people. The day after Coldstore, the Sunday Times reported that there were plans for “a period of bloodshed and disorder.” No evidence has ever been produced to corroborate these claims. And no arms were ever found in the homes of Barisan members or any individuals detained under Coldstore.

It is sometimes said that Singapore’s independence was won by the PAP through peaceful, non-violent means. This is true only if we ignore the violence of the state.

Almost all of those arrested under Coldstore were immediately placed in solitary confinement. “Many were physically tortured. Not a few went mad. Almost all suffered from what today would be called post-traumatic stress syndrome,” said Poh in “The Fajar Generation: The University Socialist Club and the Politics of Postwar Malaya and Singapore”. Two months after the arrests, Marshall was finally given access to the detainees. He said that the conditions in prison were “radically worse than conditions imposed in the past either by the Imperial Government or by any previous Singapore Government.”

Such treatment was justified on the grounds that the public were being protected from a “bloody” insurrection. As far as British declassified documents are concerned, however, the “threat” seems to have been more about the potential fall of the PAP government, than by the rise of a Communist Singapore.

Examining the spectrum of leftists in the early 1960s, how would the government have accurately detected the end of socialism and the start of Communism? Or discerned any clear line between peaceful agitation and violent action? Chin Peng made two seemingly contradictory statements in his memoirs. On the one hand, he said that, contrary to popular claims, the MCP never controlled Barisan Sosialis. On the other hand, he also contends that “Operation Cold Store [sic] shattered our underground network throughout the island. Those who escaped the police net went into hiding. Many fled to Indonesia.”

Was Lee, to quote a Chinese proverb often used to describe his methods, killing the chicken to scare the monkeys? During the second world war, he had learned about wielding power by instilling fear. “Japanese terror and torture settled the argument as to who was in charge,” he wrote in his memoirs. “And could make people change their behaviour, even their loyalties.” The war’s conclusion also entrenched his belief that the ends always justify the means. The thousands of innocent lives lost in Hiroshima and Nagasaki were worth it, he believed, for without them many more might have died.

It’s possible then that Lee’s purge of his former colleagues in 1963 was expedient both from a narrow political perspective (eliminating parliamentary opponents), as well as a broader security standpoint (nullifying the MCP’s threat), while also being a gross violation of basic human rights. This, perhaps, is the messy complexity that Singaporeans must now embrace, in our quest for truth and justice.

Contemporary historical debates, between the likes of Thum and Ramakrishna, tend to dwell on Lee’s motives. Yet even if, as the establishment says, Lee was driven only by security and not political motives—a big “if”—that still doesn’t excuse any abuses of power. One can sympathise with Lee’s supposed intentions while condemning some of its outcomes.

Detention without trial, the absence of due process, solitary confinement, allegations of torture: whatever their realpolitik justifications in the 1960s, these are not hallmarks of a democratic society. Singapore should investigate them, as it should subsequent possible abuses of the ISA, including against the 22 arrested in 1987’s Operation Spectrum, who are alleged by the government to have been plotting “a Marxist conspiracy to subvert the existing social and political system in Singapore, using communist united front tactics, with a view to establishing a Marxist state.” (Last year Jom profiled Chew Kheng Chuan, one of the 22, who recalled an ISD officer slapping him 50 times until he bled.)

Lee persisted with these methods well into the 1990s, when Chia Thye Poh was finally released, long after the MCP had laid down its arms and with the global “Red Scare” a distant memory. This is an indictment not only of him but all his enablers. By the 1980s, Lee had ushered many of his political contemporaries such as Goh Keng Swee and S Rajaratnam—those best placed to stand up to him—into retirement. Perhaps those who remained were blinded by his aura.

Investigations into these numerous operations, perhaps through commissions of inquiry, will demonstrate society’s willingness to address head on accusations by political opponents. Whatever the outcome, an honest and independent process will go a long way towards healing divides, invaluable in an era of growing global political polarisation.

Another reason to initiate independent commissions of inquiry into these alleged abuses is simply that it’s an important step in Singapore’s maturing as a society. One of the many things that distinguishes open societies from closed ones is the ability of society to look itself in the mirror, blemishes and all, and to own it, to deal with it, and to move on. The period of self-reflection and -interrogation, knotty and discomfiting as it must be to some, is necessary for growth, for self-cultivation, for nurturing confidence and pride in one’s place in this world. “One way that Singapore can confront its past is through the figure of Lee Kuan Yew,” wrote Mavis Puthucheary, James’s widow, yesterday.

Poh and others have addressed their statement of demands to the PAP, but in reality all of us are implicated—or, at least, all adults—through our silence, through our votes, through our taxes, through our unquestioned reading of PAP-crafted history. Since Lee’s passing, his fellow politicians and other acolytes in the establishment appear focused on pruning his image for the masses, on preventing alternative narratives from being aired. The unidimensional smiling good guy is whom we’re supposed to remember.

It’s why, for instance, that Tan Pin Pin’s “To Singapore with Love” (2013), featuring interviews with exiles, remains banned. (It’s easier, in other words, to watch those flicks about Pinochet and Suharto than one from our own.) It’s also why even as the UK has declassified records from that era Singapore continues to jealously guard them, offering access only to friendly researchers like Ramakrishna.

“If a government agency wishes to open its records, it should not do so selectively…Is it right to deny access to researchers who may take considered but contrary views to an official perspective?” Tan Tai Yong, former head of Yale-NUS College, said in 2015, in a discussion about the limited release of Coldstore files.

It’s also why even the slightest deviant is grabbed by their neck and shoved back in line. Recall how in 2018, K Shanmugam, minister of law and home affairs (and self-made historian), grilled Thum for six hours at a Select Committee hearing over the latter’s research on Coldstore.

Why is the PAP so afraid of an honest appraisal of Lee? It could be that, despite its apparent electoral dominance, the party is actually at one of its lowest ever points: led by Lee’s eldest son, whose popularity is waning (as many believe he’s overstayed his tenure while his siblings have denounced him); riven by some infighting; and facing, in today’s WP, the fiercest opposition it ever has (since Barisan, which itself merged with the WP in 1988).

To the faithful, the party’s legitimacy flows through the legend of Lee. It’s true not just of his dealings with political enemies, but of any contentious issue, such as racism—Lee’s historical extremities are blotted out, never to be discussed, as if they occurred in a parallel universe with no bearing on this one.

But even Lee in 2010 admitted that he did “some nasty things, locking fellows up without trial.” Moreover, the Chinese Communist Party rehabilitated Mao easily after (somewhat) acknowledging his sins. “70 percent right and 30 percent wrong,” in Deng Xiaoping’s witty reflection. The process here will be smoother partly because Lee’s alleged sins are milder. “At least we didn’t kill them,” is a common refrain from his apologists, suggesting that he deserves kudos for not executing his enemies (like other leaders did).

The implication is that any suffering by Singaporeans was negligible. Yet if that were the case, surely Poh and others would not be trudging around seeking justice and striving to open Singaporean eyes. “I am now 91 years old and am one of about 50 survivors of Operation Coldstore alive today,” he wrote yesterday. “In 1963, most of us were in our youthful twenties.”

Having spent 60 years telling us what to think, the PAP might want to consider finally listening. It may well realise that the whole world still lives with the scars—its fellow Singaporeans too.

If you enjoy Jom’s work, do get a paid subscription today to support independent journalism in Singapore.

Fiachra Ross is interested in anti-colonial nationalism, federalism, and racial capitalism in twentieth century Southeast Asia. He is currently pursuing his MPhil in World History at the University of Cambridge. Sudhir Vadaketh is Jom’s editor-in-chief.

Jom’s house style is not to include footnotes but to indicate sources through hyperlinks or in the text. Given the nature of this topic, we are including here an extra note that denotes specific references.