The burden of unpaid, informal care is becoming more widely shared by the young. This is due to a confluence of factors, like people having children later, family sizes shrinking, a growing number of single-parent families, and most recently, the pandemic, which led to children and young adults spending more time at home.

In the following photo essay, Singaporean photographer Alecia Neo captures the juxtaposition of strength and vulnerability in her portraits of four young caregivers—Iman, Mason, Sarah and Tasneem. Also featured is Amy, a single mother with schizophrenia, whose teenage son is her caregiver.

A long-form essay, “Generational shifts in caregiving” accompanies this piece, and can be read here.

Mason Chia, 26

When Mason, a psychology major, is not in class, you’ll find him at a café-bar in Boat Quay: brewing coffee in the day and mixing cocktails at night. His true calling, though, is to be a peer caregiver, offering advice and a willing ear to people his age who are coping with mental illness, or an emotional crisis. “Humans need humans,” he said. Indeed, not all young people who become carers do so out of familial duty or obligation. Altruism is a compelling motivation for some.

Young people who willingly devote time to friends or acquaintances in need are unlikely to consider themselves “caregivers” in the strictest sense of the word. Mason is cognizant of the potentially “paralysing” expectations that come with the term “caregiver”, and prefers to prefix it with “ad-hoc”. Nonetheless, young, informal caregivers like him play a vital role in the ecosystem of care.

Admittedly “apathetic” growing up, Mason’s worldview changed when he experienced deep “psychological stress”, and realised that many of his peers were probably feeling the same, and needed someone they could confide in. He's generous with his time, but not at the expense of his own physical and psychological health. Burnout is a real issue for caregivers, and Mason avoids it by knowing when to say “no”. Alone-time and introspection are essential.

Iman Hakim, 29

At 22 years old, Iman (right) took on the momentous task of caregiving for his grandaunt (left), or “nenek” (grandmother in Malay) as he preferred to call her. She had never fully recovered after a fall, and was unable to move independently, requiring round-the-clock care. Iman was the only family member who was able to take on this responsibility at the time, as his parents were working and his two sisters were still completing their diplomas.

To step into his caregiver role, he had to quit a job as an assistant theatre educator. For nearly two years, Iman administered his grandaunt’s physical and social needs, while juggling a part-time Bachelor’s degree in English. But he eventually reached a breaking point, and turned to his mother and sister for assistance. With their help, he could head out of the house for a run or some fresh air to clear his head. He was also able to dedicate more time to his studies.

On July 19th, his nenek finally succumbed to her chronic illnesses, including diabetes and Alzheimer’s. His family is grieving; coming to terms with their loss, for not only someone they loved, but also for no longer being caregivers, a role that has become embedded in their identities. At some point, Iman hopes to pick up from where he left off, and start to build his career and to rediscover his aspirations.

Tasneem Abdul Majeed, 23

Tasneem’s (right) relationship with her father, Dr Abdul Majeed Bin Abdul Khader (left), straddles a delicate balance between tension and tenderness. Both are caregivers to her younger brother, who has autism spectrum disorder (ASD), and the intense pressures on a small family can fracture even the closest of parent-child connections. But shared interests in psychology—Tasneem is a psychology major and Majeed a forensic psychologist—and advocacy work give them plenty to bond over. They also volunteer with Caregivers Alliance Limited (CAL) and the Rainbow Centre. Majeed has long recognised his daughter’s contributions to the family, and has encouraged Tasneem to share her experiences as a caregiver and sibling.

When Tasneem was five years old, her younger brother’s ASD diagnosis would significantly change her childhood. The severity of his condition means he is non-verbal and requires full-time care from their parents. Unable to fully comprehend why her brother had become the centre of attention, Tasneem ended up blaming herself, believing that she had behaved poorly to deserve this shift in her family’s dynamics.

Despite the persistent feelings of envy, anxiety and frustration, Tasneem grew to understand her brother’s needs, and started to find ways to lighten her parents’ caregiving load. Some of this included administrative tasks, like designing and printing out signs that inform strangers, while on holiday, about her brother’s condition and sensitivities.

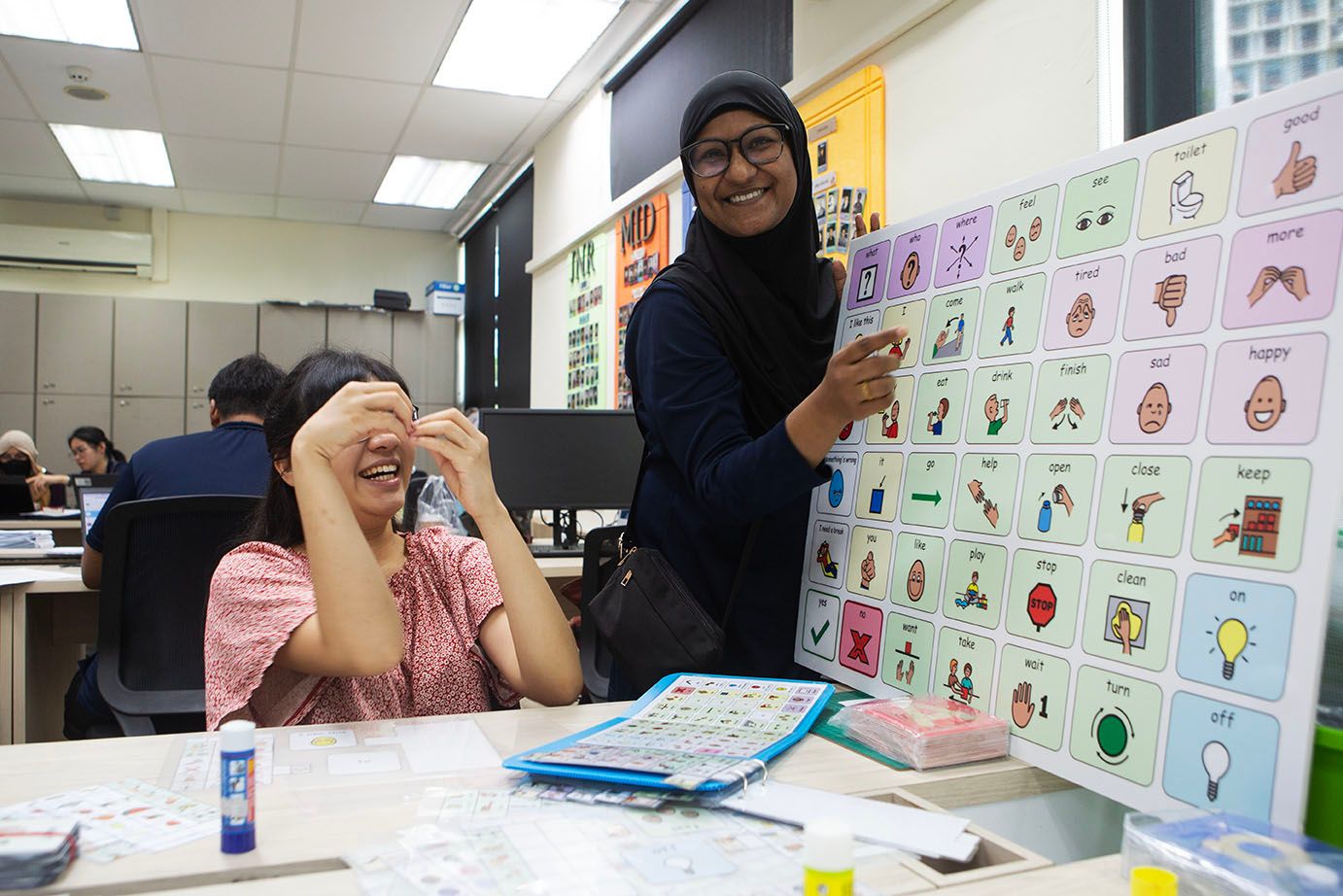

Tasneem shows a staff member at the Rainbow Centre one of her favourite signs, which means “more”. Her first public speaking event, something her parents had encouraged her to do, lit a fire in her belly. She realised that there was a severe lack of support for sibling caregivers, and set out to fill this gap by sharing her experiences and being a mentor to others like her.

“Po-po” (maternal grandmother in Chinese) looked after Tasneem as a child, complementing the family’s caregiving responsibilities. Drawn to her warm and cheerful personality, po-po (right) became Tasmeen’s “safe adult”, a trusted and unconditional source of comfort and stability. She would often escape to her po-po’s home after school to find solace.

Sarah Pang (not her real name), 26

Deep in the throes of the pandemic, Sarah’s younger sister was diagnosed with schizophrenia. Her family, including her parents and two younger brothers, were initially in denial. As the symptoms escalated, Sarah watched, confused, as her sister’s personality changed. Soon, she could no longer recognise her.

Determined to offer Sarah's sister a lifeline, the Pang family’s love and care for each other has continued to grow over the past few years, nourished by their shared purpose. For Sarah, devotional music and her religious faith have also brought a sense of peace and calm, even when it felt like her world was disintegrating.

Amy Kang, 48

At 19 years old, Amy was diagnosed with schizophrenia. The symptoms appeared suddenly and escalated over several weeks. One day, on the top floor of a building on her polytechnic campus, she heard voices asking her to throw a potted plant over the edge. She obeyed. No one was injured but a few hours later, the police apprehended Amy and brought her to the Institute of Mental Health (IMH), where she was hospitalised for five weeks. Nearly 30 years on, the mother-of-one is in a much better place mentally, with the help of medication and meditation. She has single-handedly raised her son, straddling a job as a delivery rider and a metaphysical consultant, offering spiritual and holistic advice to clients online.

When Amy experiences lapses in her mental state, and seems emotionally unstable, her 15-year-old son passes her his teddy bear to help calm her down. Their relationship has deepened over the years since her divorce. Despite his young age, her son has taken on caregiving duties at home, making sure his mother takes her medication, which helps to control symptoms like psychosis, and has made her feel more grounded. He also keeps her company after school and during the weekends.

Exercise is key to maintaining a healthy mental state, and her son ensures she gets a workout by playing basketball with him at least once a week. Sometimes, Amy noted with a laugh, her son acts like a parent. The easy reversal of roles between them has equalised their relationship and brought them closer.

Amy was particularly attached to her mother growing up. A hawker, she would hop on a bus for an hour-long ride to deliver lunch to Amy when she was warded at IMH. After Amy’s father killed himself, her mother was left to raise her children alone. They’re a tight-knit family. Amy’s siblings—two brothers and a sister—have stood by her throughout her life: advising her on work, parental and financial matters.

Alecia Neo is an artist and cultural worker. Her collaborative practice unfolds primarily through installations, lens-based media and participatory workshops that examine modes of radical hospitality and care. She is currently working on Care Index, an ongoing research focused on the indexing and transmission of embodied gestures and movements that emerge from lived experiences of care labour. She is the co-founder of Brack, an art collective and platform for socially engaged art and Ubah Rumah Residency on Nikoi Island, which focuses on ecological practices. Active since 2014, her ongoing collaborations with disabled artists currently manifests as an arts platform, Unseen Art Initiatives.

Tsen-Waye Tay is Jom’s head of content. For this piece, she’s deeply grateful to Cyan Khoo and Tricia Lee from CAL, who were generous with their time and knowledge. They also introduced her to Mason, Sarah and Tasneem.

Letters in response to this piece can be sent to sudhir@jom.media. All will be considered for publication on our “Letters to the editor” page.

If you enjoy Jom’s work, do get a paid subscription today to support independent journalism in Singapore.