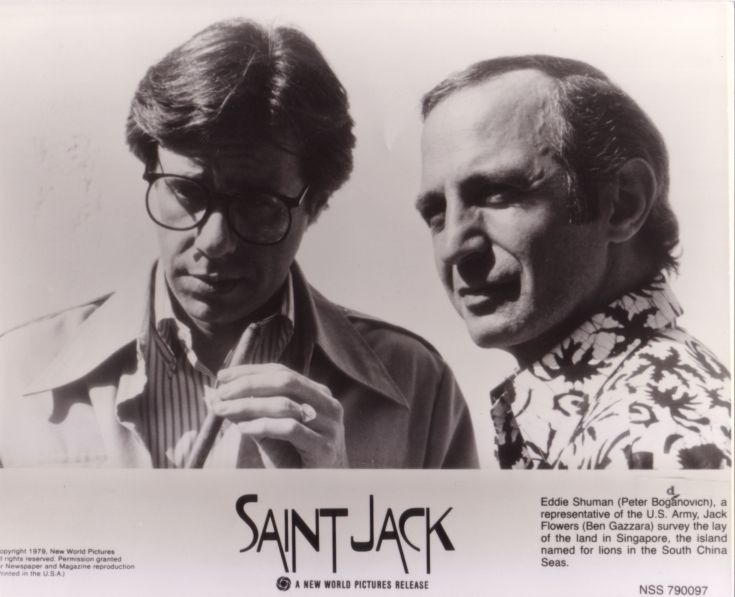

My favourite film about Singapore happens to not be ‘local’. It’s 1979’s “Saint Jack”, by the Hollywood director Peter Bogdanovich. It was adapted from the travel writer Paul Theroux’s account of our once-fabled Far Eastern emporium, and shot on-site through some careful deception. The PAP regime, determined to scrub away the thriving underworld that “Saint Jack” depicted, banned local distribution.

When I saw “Saint Jack” earlier this year, I was moved. One commentator argued that it is a Singapore film precisely because it makes us yearn for places we have never visited. Today you can hardly imagine Singapore’s past even if you tried. Gone are the old Malay settlements hugging the southeastern coast with their evocative names: Bedok Laut, Padang Terbakar, Telok Mata Ikan, Ayer Gemuroh. (I sometimes like saying these names to speak them out of oblivion.) So too are the merchant-houses of Raffles Place and the opulent waterfront of Collyer Quay.

“Saint Jack” recorded the texture of that ‘old’ Singapore, with its food-carts, Chinese street wayang, and queer Bugis Street. Yet even then they were already disappearing. The first skyscrapers had begun disrupting the fabric of the shophouse townscape. The sound of pile-drivers, still audible today in Singapore’s soundtrack, haunts the film off-screen. According to cinema scholar Ben Slater, the Lion City that Theroux wrote about in 1971 had changed by the time “Saint Jack’s” crew arrived. To me there is something heroic about their rush to capture the story in its original space: a Singapore not postcard-perfect but a seedy realm of organised crime and secret trades.

Graphic and morally questionable as the film was, it portrayed a genuine social reality: foreign hustlers relied on local collaborators to gain access, and understood the limits of their mat salleh privilege. Unlike that other much-vaunted international film made in Singapore, “Crazy Rich Asians”, Bogdanovich’s piece was much more interesting because it revealed Singapore’s dysfunctionality. It conspired with local talents, who delivered lines in Singaporean accents, and Singaporean languages. Most did not see the film until many years later due to the ban. Perhaps this is why the film enthrals me so much. The past is not seductive because it is picturesque, but because it is disobedient.

Today, I like to think that one of the last few places where the energy of that boisterous entrepôt survives is Geylang. Its shophouse facades and five-foot ways display their decay and grime. Resolutely ungentrified unlike Katong or Telok Ayer, not all its doors are open to well-heeled yuppies. Of course, I’m under no illusions that it somehow escaped the sanitising reach of the State. Like all things in Singapore that seem off-beat, Geylang is untidy on purpose. Rem Koolhaas famously described our city as “pure intention; if there is chaos, it is authored chaos; if it is ugly, it is designed ugliness; if it is absurd, it is willed absurdity.” Hence the value of an artefact like “Saint Jack”, fully inhabiting a more unsettled period when the PAP had not yet destroyed the components of a ‘freer’ city: student protests continued throughout the 70s, and Nanyang University would only be swallowed up by NUS a year after the film’s release. (We seem to have a knack for closing universities by ‘merging’ them.)

The past, therefore, contains many paths not taken. Surely it also represents possibilities for the future. Before we even consider those, however, what the past offers me is more abstract: room to belong.

In its commodified form, Singaporean nostalgia is pretty kitsch. Think Dragon Playground keychains, Good Morning Towel pins, and other such merch. But because much of present-day Singaporean ideology is built on dismantling memory and forgetting historical events that don’t conform to the PAP’s official narrative, remembering becomes an inherently political act. To cherish the Singapore of “Saint Jack” opens up a different kind of belonging: rooted not just in space, but in time. We don’t just have this one physical Singapore here today to love, but the many that have existed before, and will. We can identify with the streets, hills and paths that are no longer, but endure because we choose to remember them. This gives new meaning to “There’s a place that will stay within me / Wherever I may choose to go”: there are bits of Singapore that only really exist today in our dreams. We are all, ultimately, exiles.

In writer Alfian Sa’at’s short-story collection “Malay Sketches,” the brothers Helmy and Hazry argue over whether to leave or stay in Singapore. The elder, having migrated to Malaysia, thinks his future lies in joining a Malay-first society. “But our past is in Singapore,” Hazry replies. “So if we all leave, then who’s going to stay behind?”

In another story, Bob finds solace in the Singapore of the Malay prima donnas. Alfian himself has said, “I think one of the reasons I still like Singapore is because some of the most amazing songstresses that I adore—Rafeah Buang, Kartina Dahari, Zaharah Agus, Sharifah Aini and Saloma—were all born in Singapore.” The last two are the only singers to receive the title ‘Biduanita Negara’ (National Songbird), awarded by the Government of Malaysia. We had once given the Malay world such goddesses. Pilgrims occasionally descend from across the Causeway for a peep at the Jalan Ampas film studios (or what’s left of it). To think, despite all this money and glass and steel, we are sacred ground.

I wish we didn’t have to find such arcane reasons to like this place. But what else can you do when the love expected of citizens is a toxic one: non-negotiable, unconditional and patrimonial? Critics are chided for being ungrateful despite the privileges they enjoy as citizens. Our leaders don’t seem to understand that pointing out flaws, usually harsh, is also a kind of care. It escapes the narrow conception of ideal citizenhood the State demands from its people, who experience belonging in complex ways. Tommy Koh, ambassador-at-large, even had to coin the phrase ‘loving critics’, to illustrate that.

Part of it can even be realising that one is attached to Singapore beyond the nation, and that rituals of national celebration, like the National Day Parade, are inadequate to articulate that complicated relationship. Historians question the extent to which Singapore’s heterogenous pasts can even be made meaningful in terms of the nation. The nation, after all, is so new and limited. In fact for most of recorded history people tended to identify with their city, town or village first. Many still do, like New Yorkers and Hong Kongers.

The city—diverse and cosmopolitan—has frequently been simultaneously a part and apart from later territorial nations that swallowed them and demanded conformity. But Singapore today, both city and territorial nation, is an anomaly among anomalies. Conveniently in Malay the city-ness of our island has always been captured in the name Singapura, even in quieter periods. And that city-island has also been embedded in a network of other centres, the maritime neighbourhood of the southern Melaka Straits: encompassing the Riau islands, the Johor river system and coastal Sumatra.

Johor dynastic chronicles place Singapura among successive seats of local power and trade in this area, including Bintan and Palembang. It was a world within a world, interacting with Malay-speaking port-towns further up the Peninsula and in distant Java. But the people who served the Malay royal line, which ruled this straits world and considered it their traditional homeland, were the Orang Selat (the ‘people of the straits’). I want to inherit this identification with the water, that restores Singapura’s spiritual relationship with a sea that touches familiar shores. It dissolves the hard concrete and roads of an island that has turned inward: solitary, exceptional and paranoid.

“Saint Jack” reveals the difficulty of rendering an in-between place permanent. Its mongrel cast of sojourners, embodying the entrepôt spirit, subverts the fixed concept of ‘home’. Like the empires that briefly came before it, the Singapore nation we know today is also fleeting, the temporary master of a fugitive landscape. We are ripples on time’s grand current. But in identifying with Singapura beyond the nation, I opt for a bountiful belonging.

Faris Joraimi is Jom’s history editor. This essay is one of several that Jom is publishing free to coincide with Singapore’s 57th National Day.

If you enjoy Jom’s work, do get a paid subscription today to support independent journalism in Singapore.