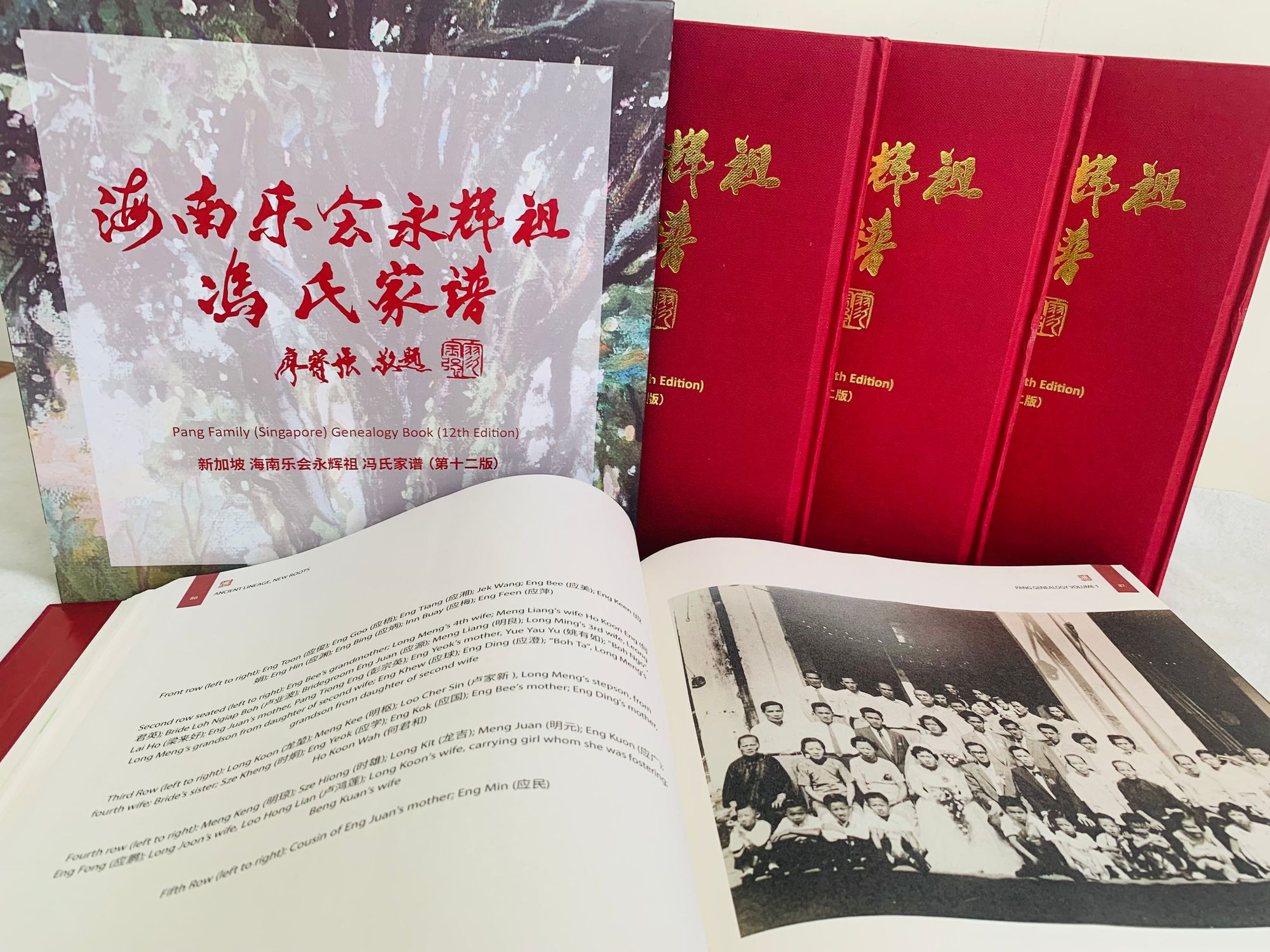

Last year, the Pang family published the 12th edition of their genealogy book (家谱). It’s a 1,700-page, four-volume behemoth that dates back to their ancestor from the 14th century, Feng Yonghui, an imperial scholar who was posted to Hainan Island as a government official. First published in 1417, the latest edition features: a volume which covers the history of the Pang family (their Chinese surname Feng was romanised to Pang); a second volume on family laws and mottos; and a third and fourth that contain biographical information of family members.

Pang Sze Yunn, chief executive of neuroscience company Neurowyzr and mother of three, was born 23 generations after Feng. In 2020, she spearheaded the project to update the book, and translate it from classical Chinese into modern Chinese and English; “It makes our family story meaningful…for Singapore’s current and future generations,” she said, “I [want]…young family members [to] understand their roots.” In this edition of the book, Pang decided to include the women in her family—a first for them and a departure from tradition, since genealogy books typically only include sons.

Jom asked Pang about the motivation behind this decision and the role of clan associations in Singapore today. (She’s part of the 200-member Fong Clan General Association.) Stressing the importance of intergenerational story-telling, she urged all Singaporeans to document our own family histories—including the unflattering, messy bits—to gain a deeper, richer understanding and appreciation of our heritage.

Her responses to our e-mail Q&A, edited for clarity and length, are below.

Jom: Some conservatives might argue that by tweaking century-old traditions (such as including women in genealogy books), we are diminishing the value of these long-established practices. Why was it important for you to include women in the Pang genealogy book? And how did you and your family reach this decision?

Pang Sze Yunn: My family has always celebrated the achievements of daughters as well as sons. Like most Chinese families, education is important for us. In my grandfather’s home, the picture of my aunt’s university graduation portrait hung together with my uncles’ graduation portraits. There were equal hopes and expectations that granddaughters and grandsons would study hard and do well in school. And when we did, my grandfather equally trotted us out annually at the Coffee Merchants Association to collect our prizes. It is perhaps a reflection of this family culture that in the production of the genealogy book, discussion about female exclusion never arose. The idea that anyone would oppose the inclusion of women never crossed my mind.

When I researched how our family planted its roots in Singapore, the role of women came up again and again. My family ran a kopitiam [coffee shop] in Mohamed Sultan Road when they first moved here from Hainan Island in the early 20th century. Family members remembered a great-grandaunt who was responsible for the financial matters, another great-grandaunt who learned to read and write by standing outside the window of a local school and observing, and numerous others who educated themselves, worked at the kopitiam, and cared for the children.

If we had omitted these stories, our family history would not only be incomplete, it would also be untruthful.

Traditional Chinese culture, which is greatly influenced by Confucianism, is very much patriarchal in nature. How do you think we can create space for women in today’s Chinese culture?

PSY: In practice, the role of women in Chinese history has changed from era to era, and differs between communities and from family to family. Chinese women are often powerful within their families, and dominant within kinship relations.

In my direct bloodline are many examples of women who have gone against the view of women as passive and subservient participants. One example was Lady Xian (冼夫人) (512-602 AD), an ethnic minority from the Li tribe, who married into the Feng family in the Liang Dynasty (502–558 AD). Before marriage, Lady Xian was already a respected tribal leader in her own right, famous as a leader who cared for her tribe and led troops into battle against local rebels. In fact, it seemed that her husband, Feng Bao (冯宝) had married her in order to ally himself with her more powerful family. Indeed, some of Feng Bao’s later political accomplishments were attributed to Lady Xian’s wit and contribution.

Within the strictures of cultural norms of the day, Chinese women have managed to push against constraints and to carve out necessary and impactful roles within families and societies.

In the past, Chinese clans played a significant role in Singapore by supporting their members and larger communities socially, financially and even politically. What do you think is the role of Chinese clans in Singapore today?

Because the modern state provides much of what we need today, and because Singapore has been stable since independence, clan associations have played a comparatively smaller role in our generation’s survival. As such, we have forgotten that as recent as 100 years ago, with no state power in colonial Singapore to take care of them when they arrived, clans cared for newly arrived relatives. In my family history, even those who shared a common ancestor as distant as 10 to 13 generations ago were welcomed. So ironically, the declining role of clan associations is a reflection of how fortunate Singaporeans have been. Today, we no longer need clan associations to support us. However, amidst the winds of change in our macro-environment, we should not too quickly say that such clan solidarity has become irrelevant and unnecessary.

Today, the concept of clans [like mine] challenges prevailing norms that we can choose our spouses, our friends, our jobs, where we live, and also leave them at will. They are a reminder that just because of a common surname, a common dialect or a common geographic origin, and not by choice, people can stick together and be loyal to each other. Of course, clans [like mine] have their rules. Our family laws specify situations when someone could be erased from the genealogy book. Nonetheless, there is power and comfort in knowing that there is a group of people who will always stand by you.

In The Straits Times article, “Genealogy book that traces 600 years of S’pore family history to include women for first time”, you stressed the importance of understanding one’s family history. For those who may not have a family genealogy book, how can we emphasise this importance to the next generation?

Knowing our family histories makes us more resilient. Across 2,500 years of my family history, and against historical backdrops that they had no control over, the Pang family seemed to have done their best with the cards they were dealt, overcame and persevered. In groundbreaking research on children, Drs Marshall Duke and Robyn Fivush from Emory University found that the single best predictor of children’s emotional health and happiness was whether they could tell their family story. Children who knew more about their family stories had a stronger sense of control over their lives, and higher self-esteem.

Family histories can begin at any time. The lack of a genealogy book should not be a hindrance. I would encourage two simple activities:

First, write a short tribute to your parents, share it with your siblings, children, nieces and nephews, and save it for future generations. Record simple facts about your parents’ lives, where they were born, what school they went to, where they lived, where they worked, who their friends were, how your parents met, etc. Write down what you have learnt from them and appreciate about them. It will give you a chance to talk to your parents, and may give you unexpected insights into your own life. I have no doubt your parents will appreciate this. For those with children, you will be modelling to them the value you place on family stories.

Second, for those with children or nieces and nephews, tell them your family stories. This is especially important during their adolescent years when their identities are forming. Encourage intergenerational story-telling, especially with grandparents. If possible, extend the storytelling to aunts and uncles. Share the difficulties the family went through and talk about how the family bounced back. There is no need to whitewash the difficulties and erase “black sheep”. Try not to omit people that you disapprove of. Children need to know that there are misdeeds and fallouts, but there is also forgiveness and reconciliation, and therein lies the meaning of “family”.

You will find that when you do this, you and your families will emerge richer in spirit and open to new challenges.

In Singapore This Week, find out why local clan associations have cautioned against stigmatising people from Anxi, a county in China’s Fujian Province, which Chinese media here have apparently referred to as a “fraudsters’ hometown”.

Jean Hew is Jom's head of research.

If you enjoy Jom’s work, do get a paid subscription today to support independent journalism in Singapore.

Letters in response to this piece can be sent to sudhir@jom.media. All will be considered for publication on our “Letters to the editor” page.