There has been much disquiet in Singapore recently. Inflation is rising incessantly, with cars now firmly out of reach of the middle class. Anecdotally, one hears of an increasing number of professionals, managers, executives and technicians (so-called PMETs) working in the gig economy. People are worried about whether their Central Provident Fund (CPF) savings will see them through their retirement and Singapore’s formidable (but largely untouchable) reserves are once again a hot topic of discussion.

Much of this unease can be seen in other countries too. However, Singapore’s vulnerabilities and unique top-down governance model make this more worrying. Could these problems be serious enough to cause a structural decline in Singapore’s prosperity? After all, Singapore is a young country with much of its economic success in the eighties and nineties buoyed by the tail winds of globalisation. There is no reason this should continue forever, especially since the tailwinds of yesteryears have turned into anti-globalisation headwinds.

History is full of the carcasses of once prosperous countries that fell into decline. Argentina, for example, was one of the richest countries in the world in the 1920s. Now it is a highly indebted country that is in a perennial battle against hyperinflation.

Complicating matters is that in Singapore, things are seldom what they seem on the surface. Issues that deserve serious debate are brushed off with platitudes and euphemistic blather. A combination of a vociferous government propaganda machine, a state-controlled media—whose main job, it would appear, is to keep citizens in the dark—and a society that has been taught to equate critical thinking and questioning with heresy allows many fallacies to be repeated long enough such that they take on the appearance of fact.

Many issues require interrogation. Why do so many senior citizens have a low standard of living in a “wealthy” country? Has a myopic, drill-based educational system led to high levels of dependence on foreign talent for knowledge economy jobs? Does Singapore’s growth model face serious challenges in the years to come?

Only when citizens have a clear understanding of how the different facets of the Singapore model really work can they fully engage with the government on issues confronting the country, and critically examine some of the alternatives proposed by the opposition parties.

“You see, but you do not observe,” Sherlock Holmes once told Dr. Watson. Similarly, we need to not just see but also observe, deduce and question with a keen eye. So, let us don our deerstalker cap, dust off the calabash pipe and proceed to unravel the mysteries of Singapore’s reserves and CPF.

What are reserves? Why do countries need them? How does Singapore use its reserves differently from other countries?

Many countries, especially developing ones, accumulate foreign reserves. These are typically comprised of bank deposits, treasury bills (T-bills) and other government securities denominated entirely in US dollars, or a mix of other currencies such as the Euro and Swiss Franc, and even precious metals such as gold. China, for example, is estimated to have around US$3.2trn (S$4.4trn) in foreign reserves and India around US$670bn (S$920bn).

Foreign reserves come in handy especially during crises. For example, if a country has an emergency need for imports, which usually need to be paid in US dollars; or it needs to defend its currency from speculators who think it is overvalued and attack it, as happened during the 1998 Asian financial crisis. In such instances, a war chest of foreign reserves can be used to buy one’s own currency, thus providing it support and helping avoid a meltdown.

Singapore’s foreign reserves are just over S$500bn, though it is important to understand that the “reserves” the government usually talks about is much more than this. The Ministry of Finance (MOF) defines Singapore’s reserves more holistically as our total assets (what we own) minus liabilities (what we owe). These are held by the government and so called “Fifth Schedule” entities, including Jurong Town Corporation (JTC), the CPF Board, the Monetary Authority of Singapore (MAS), the Housing Development Board (HDB), the Government Investment Corporation (GIC) and Temasek.

The assets include state land, buildings, cash, bonds and shares. The liabilities include bonds the Singapore government issues, such as the short duration T-bills that are currently popular with savers, and Special Singapore Government Securities (SSGS), which is essentially the CPF money of citizens and PRs. (More below.)

Importantly, Singapore’s reserves are not just used to ward off speculative attacks on the Singapore dollar or as a rainy-day fund. Our reserves—of which your humble CPF is a major chunk—are actively invested in financial markets, much like a mutual fund or hedge fund would do. And as we will see later, the returns from the reserves form a good part of the annual budget.

This is fairly unique globally. Countries with active sovereign wealth funds, such as Abu Dhabi, Malaysia and Norway, mostly deploy profits from their respective natural resources sectors. In Singapore, by contrast, the government actively invests the forced savings of its citizens (CPF) as part of its overall reserves.

Interesting, I thought the CPF Board controls the CPF money? Where exactly does the government invest my money and most importantly, is it safe?

The savings you put aside every month first go to the CPF Board and then flow to the government. In lieu of the CPF funds, the government issues the SSGS to the CPF Board. Think of it as an IOU or promissory note when you loan someone money; the IOU in this case is the SSGS. This makes the government liable for payment of principal and interest on the CPF money.

Simply put, the government borrows your retirement savings through the CPF Board by paying you a guaranteed interest rate on your CPF savings. So, unlike other countries such as the US, where citizens directly control their retirement savings (through so called 401k plans), in Singapore—like much else—the government controls it for you.

The government takes the CPF savings, budget surpluses (if any), proceeds of land sales, any other bonds it issues (e.g. T-Bills), excess foreign reserves from MAS and puts it all in a giant pot called reserves. (Analogous to the SGSS, the government issues MAS what’s known as Reserves Management Government Securities in lieu of the foreign reserves that MAS transfers to the government.) The reserves are invested mostly by GIC but also Temasek and MAS in a host of assets such as listed equities, real estate, foreign currencies, private equity, hedge funds and so forth. The goal is to earn a good return on the investments just like any commercial investor.

Over the past 20 years, GIC has recorded a 6.9 percent average yearly return in nominal US dollar terms (meaning without taking inflation into account). Contrary to the perception in some quarters, there is a virtually zero chance of the government defaulting on its CPF obligations. In the absolute worst-case scenario, the government can always print money to pay its obligations given that the SSGS bonds are issued in Singapore dollars. (Of course this will have other consequences, such as fueling inflation.)

Why does Singapore need to invest its reserves (a large chunk comprising public retirement savings) to supplement its tax revenues? Are we not a wealthy country?

Government drum-beating amplified by lazy journalists frequently touts Singapore’s high GDP per capita figure—US$84,734 (S$113,789) in 2023, higher than in the US, Australia, Denmark and Netherlands—as a measure of its prosperity. But given that many senior citizens drive taxis and sweep streets during their retirement years, it is amply evident to the average Singaporean that our standard of living simply does not resemble what one might expect for citizens of one of the richest countries in the world.

Why this discrepancy?

You see, Singapore is not a wealthy country in the traditional sense. It does not have a rich resource base like Qatar or Australia, nor does it have a highly educated and skilled homegrown workforce with globally successful champions like in Switzerland or Denmark.

While GDP per capita is generally a good proxy for a country’s prosperity, it can be misleading in city states and global financial hubs such as Singapore, Hong Kong or Luxembourg. In such places, the metric is skewed by the high productivity levels of global companies and financial institutions that base themselves in such hubs, thus it cannot be used as a sole measure of the prosperity of the average citizen. Consider that tiny Cayman Islands, a global financial hub and tax haven, had a GDP per capita of US$97,749 (S$131,267) in 2023!

Many of these companies, mostly with expat senior employees, have their headquarters here for tax reasons. Much of their revenues, though, may be earned in other countries. Furthermore, most Singaporeans do not work in high paying positions in Goldman Sachs or JP Morgan or Google. Instead, around two-thirds work in local SMEs which have much lower productivity—meaning that the value of the goods and services produced is low—leading to much lower salaries and living standards.

(Why is our supposedly world-class education system unable to produce globally competitive companies or enough knowledge economy workers? It’s a crucial issue which deserves its own article, with insights drawn from Schooling a child in Singapore: a parent’s frustrating journey, a free e-book I’ve published.)

Thus, Singapore’s high GDP per capita is a mere chimera. With almost 80 percent living in leasehold public housing, its knowledge economy driven by much foreign talent, an SME sector stuck in the third world, inadequate social safety nets, low blue-collar worker salaries and far longer hours worked than in most rich countries, Singapore is far closer fundamentally, in my view, to a developing country than a developed one.

I see, but Singapore has more than 7,000 global companies operating from here in some form. Surely they must contribute plenty to our tax coffers?

Over the years, Singapore has indeed done a fabulous job in attracting such firms, though they owe no allegiance to Singapore (or any other country). They will go wherever they find the best mix of a large home market, an attractive tax regime and a stable business environment. Singapore needs to constantly hustle to attract these companies and keep them happy here.

The weapon of choice in this war for attracting foreign companies—particularly for countries without a large domestic market—is tax incentives. For example, a major reason Singapore is a large Asian asset management centre that manages over S$5trn is because of zero capital gains taxes and one of the lowest personal income taxes for high-income earners.

While this is great for the foreign companies operating here, it results in Singapore having a low tax to GDP ratio in 2021 of just 12.2 percent versus an average of 34.1 percent for OECD countries. What this means is that relative to its exalted GDP figures, Singapore does not make much in taxes.

Now, compare Singapore to a truly developed country such as Denmark. This tiny country with a similar population of 5.9m to Singapore is not dependent on MNCs for growth because it is on its own a highly innovative country and the home of market leaders such as Novo Nordisk, Maersk, Carlsberg and Vestas.

For instance, Novo Nordisk (among the most valuable pharma companies in the world) has the world’s largest insulin manufacturing plant in Kalundborg in high-cost Denmark. Advanced knowledge-based economies need not be involved in the tax arms race to grow which is one of the reasons why the tax to GDP ratio for Denmark was a whopping 41.9 percent in 2022.

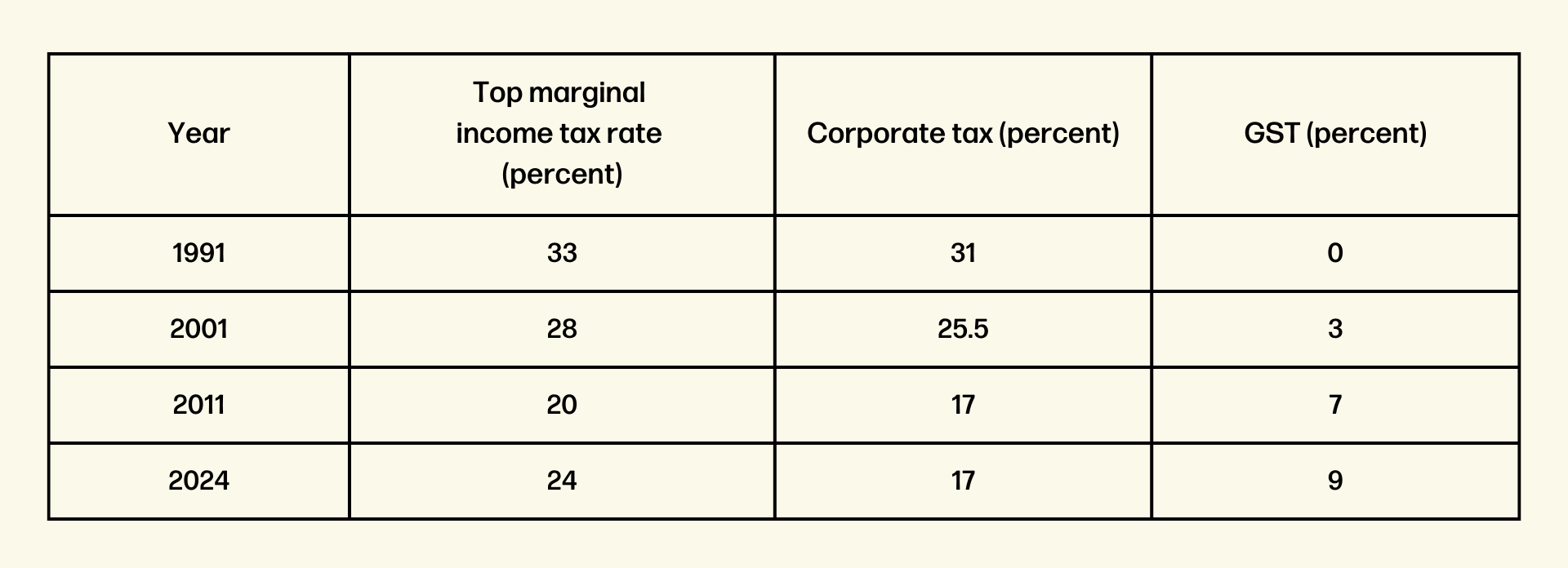

To summarise, Singapore needs to invest its reserves because its tax revenues by itself are not high enough to fund the country’s expenditure. The country lacks a globally competitive home grown industrial or service sector to grow the economy, hence it needs competitive tax rates to attract MNCs, which contribute 73 percent of its corporate tax revenues. This is precisely why GST rates have seen an uptrend over the years while corporate and income taxes have been trending down, a slight recent uptick in the latter notwithstanding. See table below:

Perhaps now you can better appreciate why some of the calls by opposition parties to increase income taxes or impose capital gains tax are off base. Decisions cannot be taken on an isolated basis; one needs to consider the entire economic model and their interlinkages.

What about our country’s trillion dollar debt? Are low tax revenues the reason why Singapore, with a gross debt to GDP ratio of 171 percent, is the third most indebted nation in the world? I have read MOF’s explanation on this, but I am still not clear.

Firstly, yes, the Singapore government does have a lot of gross debt (only liabilities). But the MOF is also right in saying that Singapore’s net debt (assets minus liabilities) is positive. Think of it like a housing loan. You might have taken a loan for S$1million to buy a house but if your house is now worth S$1.2m, you currently have no net debt (S$1.2m - S$1m = S$200,000.)

So, is there nothing to worry about as MOF says? Not really. Let’s discuss the risks with Singapore’s debt position. According to the MOF, as of end Dec 2023, Singapore had a total debt of S$1.15trn, or 171 percent of GDP. Some S$634bn (55 percent of S$1.15trn) of this debt is our CPF money. The rest is a mix between the foreign reserves (accumulated by MAS mostly from capital flows into Singapore), Singapore bonds and T-bills issued by the government.

What does the government do with all this money?

Mostly invest. Only S$11.2bn (<1 percent of S$1.15trn) is earmarked for long-term infrastructure spending. All of the rest is part of the reserves and invested in the markets. The value of these investments (or assets the government owns) is higher than the debt (the S$1.15trn) which is why the government claims that the government has no net debt hence there is nothing to worry about.

In plain English, what the government is saying is that yes, we do have borrowings but unlike other countries we do not spend this money “wastefully” on a state pension plan or unemployment insurance or providing better equipped schools and hospitals. Once spent, this money is gone. Instead, we prudently invest the money for financial returns.

MOF’s explanation, while appearing convincing on the surface, glosses over the fact that the government, much like a hedge fund, is still engaging in an inherently risky act of borrowing to invest.

Asset values are not set in stone, they fluctuate all the time. For instance, if your aforementioned fictitious house value dips from S$1.2m to S$700,000, you might suddenly have a problem if you can’t meet your mortgage payments. Similarly, commercial real estate—a market where GIC is a major participant—has fallen some 80 percent in value in some parts of the US since the Covid-19 pandemic. This asset class was seen as safe and secure for many decades.

Circumstances can change rapidly in financial markets, as happened with Dubai World, the state investment company. It had to ask for a standstill on more than US$25bn (S$36.25bn) in debt to several European banks during the 2008-09 financial crisis as real estate prices plunged globally. Ultimately, neighbouring emirate Abu Dhabi, had to bail it out.

Temasek’s recent fiasco with the beleaguered crypto company FTX shows that the state agencies are willing to invest in risky assets more suited to hedge funds. The oft-repeated argument that diversification reduces risk does not hold water during major, sustained downturns such as the 1930’s depression when all assets got decimated.

In short, there are no guarantees in the investment world. Borrowing to invest is always a risky proposition even if it looks absolutely safe when skies are clear.

A mitigating factor is that Singapore is in the fortunate position of borrowing from its own citizens with no set timelines. It has complete control of the retirement savings of its citizens and can dictate the timing of payouts to them. This is very different from fund managers who can face redemption pressure during market downturns. You can now better appreciate why the government can be very rigid on CPF withdrawal rules. Retirement savings to you is investment money for them.

Okay, so it is clear that we need to supplement our tax revenues with returns from investing our reserves. Are our reserves large enough?

According to the MOF, as of March 2024, MAS and Temasek managed a total of just under S$900bn. However, the major chunk of reserves which is managed by GIC is not revealed by the government. One of the reasons given for not revealing the full size of the reserves is that this may provide an undue advantage to currency speculators.

This reasoning would not find many takers among financial market participants.

In mid-2015, China experienced the greatest capital flight in its history and faced a strong speculative attack on its currency. It lost around US$500bn in reserves trying to defend the yuan. Finally, only strict capital controls managed to stabilise the yuan. If China with its formidable reserves and huge, globally competitive economy could not ward off an attack on its currency it is unlikely tiny Singapore will be able to.

No matter the size of the reserves, the market is always bigger. If speculators sense a deterioration in the country’s fundamentals and overvaluation of the currency, then the currency will be attacked regardless of the size of the reserves. If Singapore’s economic fundamentals do not deteriorate, then its high and consistent current account surplus, combined with its existing formidable reserves make it an unlikely target for currency speculators. (In simple terms, a current account surplus reflects higher exports than imports and outgoing payments. This is seen as positive for the currency.)

A full discussion on this topic is beyond the scope of this essay and the precise dollar amount of reserves may not even be that important. Estimates from varied sources that the reserves are in the vicinity of S$2trn sound plausible. Even from publicly available information, it is clear that for a country of just 3.61m citizens, Singapore has a lot of money squirreled away over the decades through frugal spending, investment returns and strong capital flows. In this sense, Singapore is a rich country, just that much of this wealth does not accrue to its citizens.

What is the debate on reserves all about? Why is there such a difference of opinion between the government and segments of the public on this?

Singapore is one of the fastest ageing societies in the world. By 2030 one in four citizens will be over the age of 65. So, on top of our regular spending on infrastructure, education, defence, and other areas, there would need to be increased spending on the health and retirement needs of seniors, which was not the case a decade or two earlier.

While conceding that some seniors are struggling, the government still shows an ideological resistance to social protection. It is loath to use reserves more than needed as lower reserves means lower absolute dollars contributed to the budget. It prefers to slowly increase taxes such as GST (as explained elsewhere) to fund the budget.

Many members of the public and opposition parties are against this approach. They say that rather than increase GST, which is regressive (hits the poorest the hardest), why not use more of our ample reserves for social needs? After all, they were being saved for a rainy day and it is already pouring. The evidence is in plain sight. Many of our elderly continue to engage in physically taxing work to support themselves.

Are such calls for using more reserves “populist”?

One cannot answer the question on use of reserves till the ruling party outlines its honest views on the standard of living it considers respectable for Singaporeans.

Let me elaborate. In “Minimum Income Standard 2023”, a report by Nanyang Technological University (NTU) academics, they rightly say (in my view) that “A basic standard of living in Singapore is about, but more than just, housing, food, and clothing…It enables a sense of belonging, respect, security and independence [emphasis added].”

The government however disagreed and thought that many of the needs were more aspirational, leading to higher minimum income standards. Many in the ruling party also seem to think it is perfectly normal for 80-year-olds to be clearing dishes and sweeping streets. If this is the prevailing mindset then there is not much point debating the use of reserves. As far as the ruling party is concerned, the senior citizens currently enjoy an adequate standard of living and the rainy days have yet to arrive.

In his Feb 2024 parliament speech, didn’t the prime minister offer credible reasons for not dipping excessively into the reserves and getting “heavily into debt” like other countries?

No one can deny that it is handy to have a good financial cushion in times of crisis. However, in the speech Lee Hsien Loong, then prime minister, himself admitted that “we can have no idea what the future holds”. So, anything from a great depression to an all-out war involving Singapore to an alien attack is within the realm of possibilities. Surely then, stockpiling more and more reserves is hardly the answer as it may never be enough.

Borrowing within limits during crisis times, especially with Singapore’s AAA rating and backing of hard reserves, is a more realistic option that deserves thoughtful discussion rather than being dismissed outright. (The Financial Times cited Yee Fern Phua, a director of sovereign ratings at S&P Global, who estimated that the Singapore government has amassed a liquid portfolio worth over US$1trn, or S$1.35trn—twice the level of GDP.)

It is a false dichotomy to think that one is either frugal or heavily in debt. There is a world of difference between having some debt and being heavily in debt. For example, almost all of us have mortgage debt and many use debt to buy a car too, yet we do not call such people irresponsible or being heavily in debt. Now, if someone borrows to fund vacations to the Maldives and a diamond ring for their wife (or mistress) then yes, that might be going a bit too far.

Advanced European countries such as Finland and Netherlands regularly run fiscal deficits yet have high AA and above credit ratings. These countries want a respectable, dignified living standard for their citizens (the results of which are evident in their happiness rankings), not just a pristine balance sheet to show off to the world. Not every country that borrows needs to become a Greece (during the 2011 Euro crisis) or an Argentina.

In his speech, Lee told the opposition to come clean and campaign on the basis of spending more reserves. Similarly, the PAP should come clean and make clear what kind of living standards it wants for its citizens, especially retirees, today. The NTU academics had suggested that an adequate minimum monthly income for a single person aged 65 and older is S$1,492. By contrast, the CPF’s basic retirement sum (BRS) approach—by which members set aside roughly S$100,000 by age 55 in exchange for a monthly payout of about S$1,000 from 65 onwards—indicates that the PAP believes it is far lower.

Is S$1,000 per month enough for a single elderly person to live in Singapore? Is the retiree allowed an occasional coffee from Starbucks and meal in a place other than a hawker centre? What about an occasional trip to Bangkok? Do retirees need to subject themselves to the humiliation of means testing for the rest of their lives?

What Singaporeans want to hear are clear and honest views on what they, as citizens of one of the so-called wealthiest countries in the world, can expect in their golden years? Platitudes about the good old frugal days and why spending today means starving the next generation of opportunities—another false dichotomy—do not cut it anymore. (Oh, and in the good old days, public servants did not aspire to live in 200,000 square foot mansions either, so times have indeed changed.)

The future is important but so is the present. Today’s generation of elderly people were the future generation 40 years ago.

Let us take a step back. Doesn’t Singapore have a social security plan called the CPF which is supposed to take care of the retirement needs of seniors?

The CPF is inadequate for the retirement needs of Singaporeans. Aside from the issue of HDB lease decay and the potential impact on CPF savings, it suffers from two major flaws.

Firstly, low-wage workers and those who use a high amount of CPF savings for housing have much lower contributions to the CPF, penalising them from the start. This has resulted in high proportions of CPF members being unable to meet the BRS. For instance, the “Minimum Income Standard 2023” report said that of the active CPF members who turned 55 in 2021, “only 65 percent had either saved the BRS and owned a property, or had saved the FRS [full retirement sum, double the BRS].”

The second and more important reason is the low rates of compounding that do not allow the savings to grow to a nest egg sufficient to fund their entire retirement. The end result: low contributions + low compounding rates = insufficient retirement nest egg.

Could you elaborate on low rates of compounding for my CPF savings? How does it impact my retirement?

Earlier we discussed how GIC made an average 20-year annual return of 6.9 percent on its reserves (a large chunk of which is our CPF money). However, as every Singaporean knows, CPF holders only get an interest rate of 2.5 percent on their ordinary account (OA) and 4 percent on their special account (SA).

Well, what if you earned this 6.9 percent (GIC’s returns) on your CPF? How much more would you have for your retirement?

Let’s assume you have S$100,000 savings at age 30 in your CPF. (For simplicity, we’ll ignore additional monthly contributions.) How much will your S$100,000 be worth at age 65? A CPF savings of S$100,000 compounded for 35 years at 3.3 percent—blended OA and SA rate based on simple average—will give a retirement lump sum of S$311,358.

But if, instead of 3.3 percent, the money compounded at 6.9 percent, you’d have S$1,033,383, making you a millionaire retiree!

The over three times larger retirement pot is the difference between washing dishes during your golden years or spending time on the beach in Phuket. There is a reason compound interest is called the eighth wonder of the world. Small differences in annual returns add up to a lot over the long term. While the CPF Board and Singaporeans are focused on the minutiae of CPF withdrawal timings and labelling of retirement accounts, the big elephant in the room of low compounding rates hardly sees any discussion and that is what really matters.

Can the average Singaporean achieve GIC-like returns?

While GIC’s annual returns of 6.9 percent seems high compared to the returns CPF members get, it hardly even matches the long-term return of the S&P 500 index, an equity index of the 500 largest and most competitive companies in the US. The S&P 500 has returned an average annual return of 10.1 percent since inception in 1957. While returns have been volatile, most decades have seen annual average returns above 7 percent.

All one needs to do is to buy a passive low-cost S&P 500 ETF (e.g. SPY traded on the NYSE) through any local broker. One does not need to pick stocks or understand balance sheets and cash flow statements. There is no fund manager involved. The ETF simply tracks the performance of top performing companies such as Google, Apple, Eli Lilly, Exxon Mobil and others. As they grow, so do your retirement savings. It’s as simple as that.

“My advice to the trustee could not be more simple: put…90 percent [of my money] in a very low-cost S&P 500 index fund,” said veteran investor Warren Buffett in his 2013 letter to Berkshire shareholders on where he wanted his money to be invested after his death.

If this were allowed, CPF members could do exactly what Buffett recommends by directly making monthly contributions to a S&P 500 ETF and significantly increasing their retirement nest egg.

Aren’t equities risky? What if the market crashes?

The volatility (ups and downs in the market) of equities is frequently used by naysayers to justify “safe” bank deposits. However, the curious (and smart) reader who researches the returns of the S&P 500 during different decades will stumble upon a cardinal principle of finance: as the time frame increases, the volatility of returns decreases.

What this means in simple English is that over a one- or two-year period, investing in equities can be risky. What if the Covid-19 pandemic had hit just when you wanted the money for your son’s college? However, as the time frame increases, the risk decreases. The market trends up over the long term which is perfect for growing your retirement savings. In fact, investing in equities forms a core part of what GIC and Temasek do, it is just that citizens do not get to enjoy these returns in their CPF.

Let me make it clear: I am not in any way implying that the average person can pick stocks or invest in complex financial instruments to generate high financial returns. My point is simply that an average person is very capable of investing regularly in a passive S&P 500 ETF, and just sitting back and letting their retirement account savings compound.

You have to convince me a bit more. Since the financial crisis in 2008-09, banks have been offering me negligible rates on my fixed deposits while my CPF accounts have been getting 2.5 percent for my OA and 4 percent for SA. Are you saying that was not a good deal?

Many Singaporeans, no doubt swayed by the CPF Board, make the mistake of comparing their CPF interest rates to fixed deposits (FDs) rates offered by banks. CPF funds are meant for your retirement needs and need to compound at good rates for as long a time as possible. That is how you build a healthy corpus. Bank FDs are short-term products meant for financial emergencies. Thus, they are not an apples-to-apples comparison.

The government continued to offer “good” CPF rates not out of magnanimity but because it was getting a much better deal elsewhere in the equity markets!

Let us briefly review market activity since the financial crisis.

From 2009 onwards the Federal Reserve started cutting rates aggressively and got it to less than 0.5 percent. The sub 1 percent rate environment continued till 2022 (there was a rise in rates in 2018 and 2019 but it was not significant) from which point rates started increasing at a steep pace. During this whole period the equity markets continued their ascent, albeit in a volatile manner.

Now assume that you had S$100,000, say from selling your flat, in Jan 2010, after the financial crisis had passed its nadir and markets were already rallying. (Had it been invested in 2009 your returns would be much greater.) Further assume that you had the choice of putting this money in your CPF accounts earning a blended 3.3 percent or investing in the S&P 500 ETF.

Let us see what your balance would have grown to in Jan 2024, a full 14 years later, in both the scenarios: in the CPF accounts you would have had S$157,000 after 14 long years; and in the ETF account you would be happily surprised to learn that your corpus would be worth S$581,000.

This is because while the CPF was giving 3.3 percent per annum—what you thought were generous rates—the S&P 500 was silently compounding at a compound annual growth rate of 13.4 percent over the same period. Of course, there were ups and downs, but you are not allowed to touch your CPF savings in the interim, anyway, so any selling temptation would have been avoided.

The equity markets generally do better in a low interest rate environment, so Singapore’s state investment managers were probably making good returns too and did not mind paying CPF investors a measly 3 or 4 percent.

If all this is true, then why isn’t it communicated to us clearly by the CPF Board?

As discussed earlier, the government needs the people’s savings to invest as part of its reserves to finance the budget. It needs complete control over the funds with no premature withdrawals. This is the reason the CPF rules are so rigid. Even high net worth accredited investors are not allowed to manage their own retirement money.

In line with this mission, the CPF Board peddles the narrative that the returns it offers are “risk-free” and that the interest rates are “much better” than bank deposit rates.

Both arguments are disingenuous.

Firstly, while the CPF returns appear to be optically risk-free, given the low interest rates, they in fact carry a huge and highly probable risk: the risk of washing dishes and sweeping floors during retirement due to inadequacy of the retirement corpus.

One simply cannot achieve good long-term returns without meaningful compounding through equities. With a 3 percent CPF compounding, it will take 24 years to just double your money, by which time inflation (CPF rates are not inflation indexed) would have eaten away your returns. Taking no risk can sometimes be the biggest risk!

Secondly, as mentioned above, CPF rates should not be compared to short-term products like bank deposit rates. Bank deposit rates in Singapore are suppressed due to, among other reasons, the lack of competition and lending opportunities for the banks. At the time of writing, DBS bank offers 0.05 percent for a one year time deposit of S$20,000 and above, while the latest Singapore 1-year T-bill yielded around 3.05 percent. Thus, rather than comparing your CPF rates to (suppressed) bank deposit rates, they should be compared to long-term investment products like a well-diversified index fund, such as the S&P 500 ETF or the MSCI World Index, which have historically had long-term returns of more than 7 percent per annum.

To make matters worse, the so-called “professional managed products” that the CPF does offer—in which you can apportion a small part of your CPF savings—are mostly actively managed mutual funds with relatively high fees. Bizarrely, CPF members are not allowed to buy low-cost S&P 500 ETFs directly, but instead have to go through a “CPF approved” fund (e.g. Endowus) that charges a fee for even passively managed ETFs.

Whose interests are really being taken care of here: that of the CPF members or the fund houses?

Do Singaporeans benefit in any way from the higher returns earned by the government on our CPF funds?

Since 50 percent of the returns generated by the reserves are used towards the budget, Singaporeans do indirectly benefit from the returns the government generates. In financial year 2023, this amounted to a hefty S$23bn, accounting for 20 percent of the government’s budget.

However, the CDC vouchers and various subsidies handed out occasionally by the government are in fact nothing more than returns on the people’s own money had they been allowed full freedom to invest their savings.

What would be a fairer way for the government to share the returns it makes on its reserves with Singaporeans?

The government could offer the current CPF rates as a minimum guarantee and then share the actual returns—for example, the 6.9 percent per annum GIC returns over twenty years—it makes on the CPF funds with its citizens.

This is not as unfair as it sounds. Given that a passively managed S&P 500 ETF has returned above 7 percent over most decades, even a mediocre fund manager at GIC and Temasek should be able to make above the low four percent CPF hurdle over a three- or five-year period. A one- or two-year underperformance below the four percent rate can be temporarily financed through reserves.

In summary, the realities of survival as a city state have led to Singapore’s aggressive approach in piling up reserves. Sadly, a casualty of this approach has been the lock up of CPF savings for low returns leading to high income insecurity for its citizens during old age. A better balance needs to be found between growing reserves using its people’s savings and allowing Singaporeans more control over their retirement money.

Bobby is a global investor and author. Previously he was an entrepreneur and a strategy consultant with McKinsey & Company. This is his second essay for Jom; the first one was on HDB pricing. Bobby's latest book is Schooling a child in Singapore—a parent’s frustrating journey.

Letters in response to this piece can be sent to sudhir@jom.media. All will be considered for publication on our “Letters to the editor” page.

Get a paid subscription today to support our independent journalism. It’s the only way we can keep doing this work.

This piece led to a very insightful exchange between Bobby and Shawn Low, a Jom reader. It is reproduced in full below.

I read this week’s piece, “Why Singapore’s Elderly Continue to Work: reserves and CPF demystified” by Bobby Jayaraman with interest. I thank the author for his perspectives and would like to offer a few points in response.

First, it’s worth noting that while CPF investment options have been fairly limited historically, these options have expanded significantly in recent years. In addition to roboadvisors like Endowus, Singaporeans today can deploy their CPF funds to low-cost, globally diversified index funds through commercial brokerages. As an example, the Amundi World Index fund that takes CPF monies has an expense ratio of 0.10 percent and can be accessed via POEMS (Phillip Securities) without any advisory or platform fees.

Second, the delta between CPF’s risk-free 4 percent return for long-term holdings in the Special Account and GIC’s 6.9 percent 20-year return should factor in:

- Scale of deployment: there is likely not sufficient long-duration, SGD-denominated assets for deployment, and there are foreign exchange risks and currency hedging costs to consider for deployments to investment assets in other currencies

- Duration: 20 years is arguably not quite long enough a time period for the security of long-term returns relative to retirement savings spans (30-50 years). Also, as far as risk-free assets go over the past two decades of low yields, 4 percent is fairly attractive

- Consumer behavior: the majority of Singaporeans even in their own private investments overwhelmingly place funds in super safe assets (e.g., fixed deposits, capital guaranteed endowment plans) that have historically offered even lower returns

The author makes a fair point that perhaps what the government could consider is to offer a minimum guarantee on CPF interest and then offer surplus returns to citizens periodically. However, that seems more to the tactics of how re-distribution happens, and the loss of a revenue stream ultimately has to be made up somewhere else. It is not clear that this approach would necessarily be preferable to higher taxes for example.

As a minor point, the title “Why Singapore’s Elderly Continue to Work” misses the point that there are elderly working everywhere in the world out of necessity. Perhaps the question at hand is more how our elderly in Singapore fare compared to others. Not just in wealth or GDP per capita but more in quality of life and overall well-being, which increasingly should be our barometer for Singapore’s success.

Shawn Low, Singapore

Author response:

Further to my essay on reserves and CPF, please see below some additional explanations based on reader feedback.

Will our CPF money invested in US indices not lead to excessive dependence on the US?

By virtue of being the largest economy in the world (around a fourth of global GDP) and having the world’s most competitive companies, most investments tend to have a high concentration in US equity indices. Singapore state investment agencies are heavy investors in the US anyway so it would not matter much if citizens do it themselves. The S&P 500 ETF for instance is highly liquid with an annual trading volume of around USD 14 trillion. Also, as clarified below I do not in any way advocate limiting CPF investments to the US.

Is an S&P 500 ETF the best avenue for maximising CPF returns?

The intent of my essay was not to recommend a specific investment to grow CPF savings. The S&P 500 was used merely as an example to show the compounding that can be achieved through passive equity ETFs. Investors based on their risk appetite may choose other global equity ETFs such as MSCI world ETF or even emerging market indices for parts of their portfolio. The fundamental idea is that a low cost passive ETF offers the best compounding over the long term hence is ideal for CPF savings.

What about currency risk when investing in US ETFs?

Given Singapore’s small size and limited debt and equity markets, there is no alternative but to venture outside for best returns and assume an acceptable level of currency risk. The US is the world’s reserve currency and one of the currencies the SGD is pegged to. Over the years, there have been fluctuations, but they haven’t had a major impact on equity returns. For instance, in the twenty five year period from 2000 to 2025, the USD fell from 1.80 to today’s 1.35 levels which is a 25 percent fall or 1 percent per year. Given the S&P 500’s average annual return of 7 percent, this would still mean a 6 percent net return after adjusting for currency depreciation. In general, currency fluctuations are more relevant for short term investments. There is also no guarantee in the future that the Singapore dollar would not depreciate against the USD.

Will a market crash undermine the case for equity ETFs?

As explained in the essay, market corrections do not have a major impact on long term returns as equities are mostly upward trending over the long term. Furthermore, I am not advocating putting 100 percent of CPF money (if it were allowed) into equity ETFs. This is purely a matter of individual risk appetite. Even a quarter of CPF savings allocated to equity ETFs will have a significant impact on overall returns.

The CPF board has overtime improved the range of low cost products available under CPF

It is good that the CPF board is doing their job by offering more low fees options. However members are still unable to buy a basic low-cost S&P 500 ETF through a broker. Furthermore, these investment options can only be used for a small part of the CPF savings which doesn’t move the needle much.

Isn’t 4 percent a good risk-free yield?

As explained in my essay, 4 percent is a good risk free short term yield but not good for long term compounding. Furthermore, one needs to recognise that the period post 2008 financial crisis has been rather unique in terms of very low interest rates and inflation, one should look at a broader sweep of history to understand where interest rates and inflation might head. The higher inflation regime since 2022 is already eating away the meagre CPF returns.

Singaporeans have traditionally placed their money in very low yielding bank deposits, CPF by comparison offers better rates.

In my essay I clearly explain why short term bank deposit rates cannot be benchmarked to CPF rates which are long term. Singaporeans have historically placed money in low yielding bank deposits due to poor financial literacy and lack of adequate investments products. Plenty of young people now have discovered alternate safe investment options including US ETFs. Anyway, to use the ignorance of the population to offer low interest rates on their savings sounds predatory. The government should instead educate the population on the best ways to grow their savings with minimum risk.

Will not your proposal of offering higher CPF returns (similar to GIC returns) by the government result in higher taxes?

My proposal might lead to slower buildup of reserves not necessarily higher taxes. As CPF savings bulk up people would need fewer vouchers and other handouts which will help curtail government expenditure so the net effect on the budget and reserves might not be much.

Is the lifestyle of the elderly in other countries necessarily better than Singapore?

As far as I know, there is no benchmarking of elderly lifestyles across countries. If there were one, Singapore likely would not place high. In no other country have I seen so many elderly doing physically taxing work such as driving taxis, sweeping streets, washing windows, clearing dishes and so forth.

Bobby Jayaraman

Reader response

I appreciate Bobby Jayaraman’s follow-up letter and would like to address two key points:

Is 4 percent a good risk-free rate?

On this, I believe the author and I are largely in agreement. The 4 percent return in CPF-SA functions somewhat like a long-term government bond and, compared to Singapore Government Securities (SGS) and other forms of government debt, offers an objectively attractive yield.

We also agree that over long time horizons, diversified equity investments have historically provided the best expected returns, and is a core component of most retirement portfolios. For that reason, I welcome the CPF Board’s recent efforts to expand low-cost, equity-based investment options for CPF funds and hope they continue in this direction.

CPF and Retirement Security

Where we may differ is in the author’s suggestion that current CPF construct is the reason many elderly Singaporeans continue working. On this point,

- CPF is generally highly regarded amongst the world’s retirement income systems even by independent agencies

- To my understanding, CPF was never designed to be the sole pillar of retirement savings for all Singaporeans. Instead, it serves as a crucial supplement to personal savings and family support in ensuring retirement security.

- It is worth noting that for many middle-class Singaporeans, their most significant financial asset is their home. The HDB mortgage rate, pegged at 0.1 percent above the CPF-OA rate, provides a key reference point for commercial mortgage rates—helping homeowners achieve substantial long-term savings relative to other markets.

Of course, no system is without flaws. It is certainly regrettable that there are elderly people who continue to work out of necessity in Singapore. However, rather than attributing this primarily to CPF’s rate of return, I believe it is important to examine the broader underlying causes of this issue before concluding that the system is fundamentally inadequate.

Shawn Low