We begin with the story of two birds: the sociable weaver, and the kampung chicken.

A sociable weaver’s nest often resembles the hollowed-out husk of a coconut, a dense and delicate lattice of grasses and leaves stitched together by beak. As fledglings, these industrious little creatures spend a good deal of their time poking and pulling strands of grass and blades of leaf through any holes they can find. This bird, the size of a hand when fully grown, eventually learns to weave sprawling architectural feats; their massive nest complexes, draped over anything from large trees to telephone poles, can span 20 feet in length and 10 feet in height, house several hundred birds, and last up to two centuries.

But successful nest-building requires several other factors. The late husband-wife ornithologists Nicholas and Elsie Collias, in their meticulous studies of weaverbirds, found that birds who were prevented from practising, or deprived of their materials, would never be able to build adequate nests, if at all. We might say that the birds’ abilities are choreographed by their environment, and designed by their materials. They test out structural supports, adjust their posture, hone their prehension. It isn’t just a precision of movement these birds have refined over time, but also how they move in tandem with the evolving shapes of their homes, and the leaves and grasses they gather and thread.

Sign up for Jom’s weekly newsletter

Our newsletters combine weekly updates about Singapore with a "build-in-public" narrative, in which we tell readers about our start-up journey.

No spam. Unsubscribe anytime.

The kampung chicken spends its time choreographed by more leisurely, but no less powerful, forces.

Yee I-Lann stands in front of “A map of Mansau-ansau” (2024), the woven artwork that gives her astonishing exhibition its name. She presses her hand to the warp and weft of split bamboo pus, woven into an imposing wall hanging that swallows you up in its labyrinthine pattern the moment you come close. “Mansau-ansau,” the Sabahan artist declares, shivering with delight, “is the route of the kampung chicken.” That indigenous free-range fowl found in Malaysia and Indonesia wanders all over but always knows how to get back to its perch. “At my gate I have this tree, and at night, every night, the kampung chickens are sleeping on the branches of that tree,” Yee grins.

Mansau-ansau is the Kadazan-Dusun term for wandering without a fixed destination, then returning at the end of your walkabout. It’s a definition from one of her elders, the linguist Rita Lasimbang, who spent over two decades building a dictionary of the closely related, and often hyphenated, Kadazan-Dusun indigenous languages. It’s also the name of this dizzying, dazzling weave invented by Yee and her long-time collaborators from indigenous communities: Julitah Kulinting, Lili Naming and Shahrizan Bin Juin. They were determined to create a weave that would constantly change its course. The process left them so disoriented that they often felt like throwing up, or found that they’d woven themselves into a dead end. A pattern emerged only after the trio relinquished control of the weave, resisted the urge to bend the bamboo pus to their will, but rather just followed its natural bend. They allowed the material to choreograph their movements.

Yee invites us to peer more closely at the weave, pointing out that there are no tessellations, and no repeats. Where the material goes, we must follow. This social choreography is woven through her stunning solo show at the Singapore Art Museum (SAM), one compiling two decades of socially engaged, feminist and decolonial practice in her home of Sabah. Like the sociable weaver and the kampung chicken, she and her collaborators gather materials from their environment, shape homes from embodied memory, rehearse their communal craft, embrace the wanderings of oceanic nomadisms and circular economies, and assert the right to a return home.

How might objects, materials and spaces shape the way we relate to each other? The first of three adjacent rooms housing Yee’s work sets the stage for her social choreography. Geographic location becomes a poetic invocation. Before we know where we might go, we need to know where we begin.

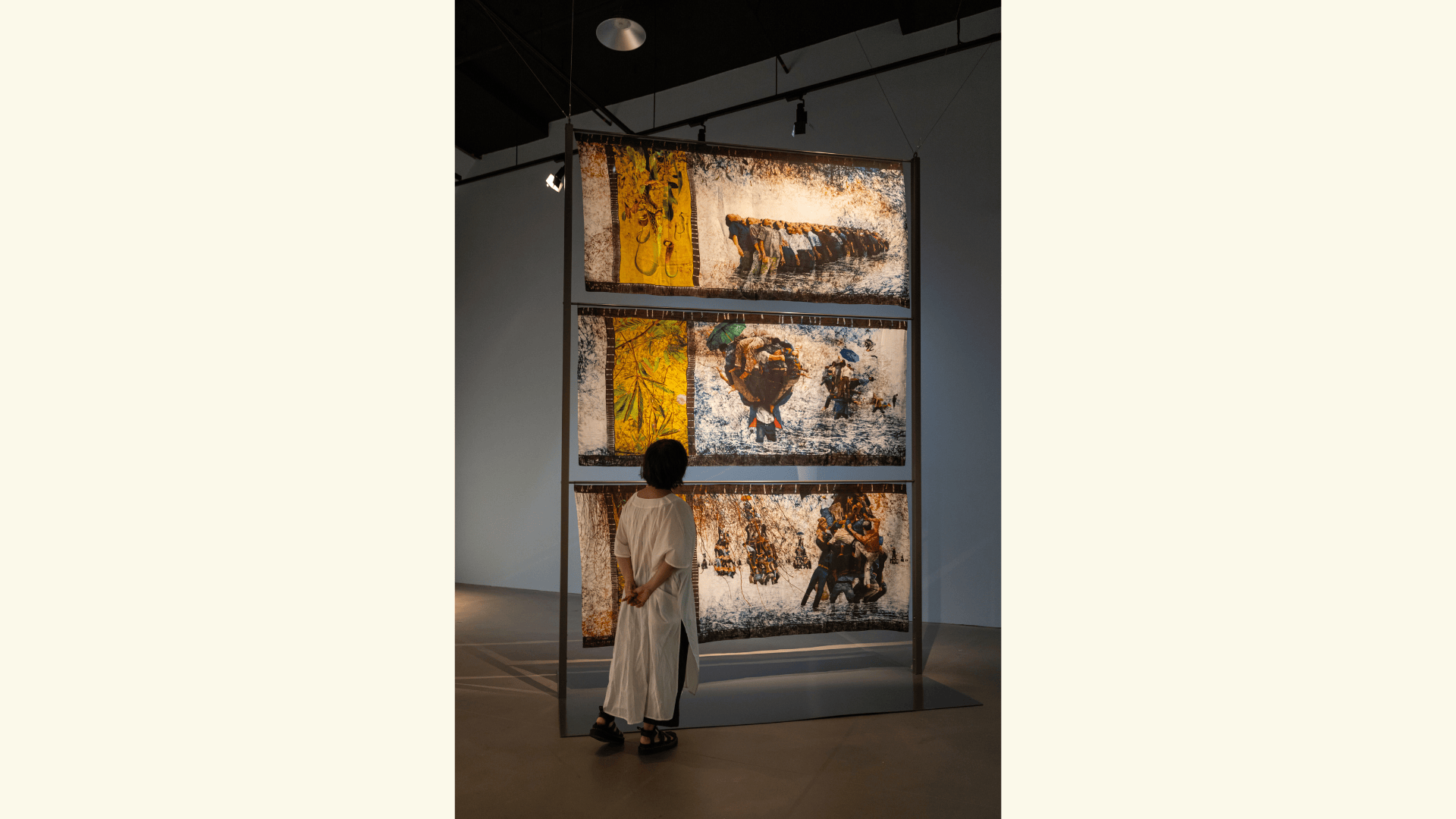

We’re greeted in the dim twilight of the gallery by “Fluid World” (2010), a luminous map of maritime, rather than terrestrial, cartographies. The suspended silk twill is scored by the cracks and currents of the wax resist method used to dye batik, and South-east Asia glimmers at the centre of an indigo pool that stretches from the wind-battered headlands of the Cape of Good Hope to Lima on the Peruvian coast. Its neighbour, “The Orang Besar Series” (2010), is a stacked textile triptych evoking the design of the kain panjang, or “long cloth” . This garment is traditionally wrapped tightly around the body, so that its wearer might only take narrow steps. The swaddle of the kain panjang evokes the limited degree of physical mobility bestowed on the ranks of the upper class, rather than the looser sarong that allows the working classes more freedom of movement. The three pieces curl and flutter at the edges, responding to the drafts that circulate through the room, almost like they’re breathing.

Lining the walls are prints from “Sulu Stories” (2005), a series of digital collages. Dynamic tableaux play out on the seascapes shared by Sabah and the southern Philippines. The fixed horizon line threads through every scene. Here, as in “The Orang Besar Series”, the ranks of the ruling orang besar or “big person” abuts the ruled orang kecil (“little person”). Yee’s chosen a staged archival photograph from 1925 as one of the images, where a gun-toting white man grabs the wrist of, presumably, a Moro warrior with a bolo knife. They’re bleached by the sun, and the local is staring down his faux colonial aggressor with a kind of benign pity. In another manipulated image, Muammar Gaddafi, the polarising Libyan leader, grasps the hand of Tun Mustapha, the first governor of Sabah and later its chief minister; together, the duo funded, trained and armed the Bangsa Moro People’s Liberation Army, which in the 1970s desired an independent Muslim Mindanao. These political leaders, including Ferdinand and Imelda Marcos peacocking with a leashed giraffe, are all posed and perched on rocky outcrops. They share the wall with members of local tribes in mistier, mystical environs, either squinting or smiling at the camera.

Multiple strands of Yee’s feminist and ecocritical thinking cohere in these installations. She favours and foregrounds the use of natural materials, ecological metaphors, and what’s traditionally assumed to be women’s work: the crafts of batik, dyeing, stitching, weaving. Her critique of structures of authority, whether in feudal contexts or colonial ones, are undergirded by this feminine presence. This intimation becomes a lot more explicit in the next room, the heart of Yee’s exhibition.

Two of Yee’s most consistent metaphors across her bodies of work are the tikar (woven mat) and the meja (table)—and the tensions between the systems of knowledge these objects represent. The way we sit at a table, or recline on a mat, also determines the ways in which we commune with each other.

In this central room, various tikar are draped across an archipelago of office chairs, but they also cover the walls, ceiling to floor, in a bright patchwork of colour. Here’s the mat for births and deaths; for surprise guests and family dinners; for loud parties and for bodies soft with sleep; for selling wares at the market; and for lounging at the beach. The tikar is laced with multigenerational knowledge; the weaving process demands mathematical and aesthetic precision for its rhythmic counting patterns and specific motifs handed down from one generation to the next. One community will recognise another’s woven language, and how their motifs are deployed not just in daily life, but also in ritual and politics.

But this isn’t simply a display of sweet, communal domesticity. We begin to realise that there is no mat on which we are invited to sit. Instead, they’re curled up like sloughed-off skins or pinned up vertically as representations of another object: the table.

Yee and the SAM curatorial team square the tikar off against the meja on the opposing wall, with an austere cluster of largely black-and-white collages. “Picturing Power” (2013), this arresting series of found photographs, was excavated and assembled from the archives of Amsterdam’s Tropenmuseum (Museum of the Tropics), and captures the colonial violence wreaked on Malaya through the prescriptive colonial administration of the table. It isn’t an army that arrives, brandishing cannons and guns, but a battalion of surveyors, census takers, teachers, and photographers cloaked in black. They’re armed with measuring instruments, cameras, and lots of umbrellas to shield them from the equatorial sun. And what they bring is a slow violence that continues to persist. “The violence of a table is telling you who you are,” Yee said in a keynote lecture at the Chinese University of Hong Kong several years ago. “A gun just kills somebody. Colonialism is inherited through multiple generations. The hurt is much worse than being killed by a gun.”

Rob Nixon, the South African anti-apartheid activist-turned-academic, describes this creeping chill of ecological and neocolonial violence in Slow Violence and the Environmentalism of the Poor. He cautions us against an “incremental and accretive” violence that embeds itself into our everyday lives and deceives us—because it is neither sensational nor spectacular in the ways we’ve come to assume violence must be. To Yee, the violence of the table lies in its extraction and replacement of knowledge systems, languages, religious and ritual practices, even clothing and conventions of beauty. Its violation is the slow forgetting of who we are.

Yee’s collaborative processes then become part of a broader decolonial choreography of restoring and repairing sociocultural memory. We’re invited to return to the tikar after contorting ourselves to fit the table. Yee frequently works with Bornean communities who are illegible or invisible to political and social administration: those who move in the gaps between the categories of race and nationality, or whose knowledge systems don’t adhere to the conventional repositories of image and text. These include the Bajau Sama DiLaut, a largely stateless and nomadic people indigenous to coastal Sabah. In “TIKAR/MEJA/PLASTIK” (2023), over 20 weavers from this community present a sprawling index of table silhouettes in mat form. They’ve incorporated ribbons of plastic waste, washed onto their shores, into their heritage pandanus weave. The tinselled trash glints like seaglass under the gallery spotlights.

Like so many of the pieces in the gallery, I longed to stroke these multi-coloured mats, ones so similar in palette and pattern to those I’d grown up lying down on. I wanted to feel my palms pressed up against this community’s textured lineage, their past made present, made physical. These tikar, it struck me, were memory and movement made material.

Diana Taylor, the performance studies scholar who studied the reverberating effects of colonialism on the Americas, introduces us to the fixity of the archive and the fluidity of the repertoire in her book The Archive and the Repertoire: Performing Cultural Memory in the Americas. She investigates performative modes of cultural production—dance, singing, gestures, storytelling—that are usually dismissed as formal knowledge because they do not have the same repeatability and stability of the objects in the archive. The actions that form these repertoires both preserve and transform the knowledge they transmit. It’s a relationship we’re all familiar with: your grandmother’s ayam buah keluak recipe is part of your family’s archive; and, when you cook it, becomes part of your repertoire.

Like Yee’s table-mat divide, Taylor sets up a tension between the archive and repertoire, where Western writing systems encroach on indigenous oral histories. But she acknowledges that the archive and repertoire also work in tandem, each filling in for the qualities the other lacks. What I marvelled at, here in the gallery, is how Yee’s work manages to be both.

Who and what do we rely on to “back up” our social memory? One of the events programmed around the spine of Yee’s exhibition featured two women who were the cornerstones of a decades-long project to build a dictionary of the Kadazan-Dusun language. Jeannet Stephen and Rita Lasimbang, both linguists and indigenous Sabahans, held a three-hour sharing session on the 22-year journey. Their team, including close family members, consolidated over 30,000 root words and their affixes, standardised their transcription and orthography, and centered community-driven content selection—allowing the Kadazan-Dusun people to define themselves linguistically, rather than subject themselves to the definitions of previous powers. In their whistlestop tour of several centuries of linguistic history, from colonialist subjugation to subsequent decolonial efforts, the dictionary transforms from arbitrary documentation tool to custodian of community knowledge. “Every dictionary we create is a map back home,” said Stephen, through tears, at the close of her presentation.

Take a mansau-ansau through the dictionary, and you’ll get a glimpse of how a language discloses its structures to those attempting to organise it. How its entries are arranged disregards some of the standard alphabetisation of other romanised scripts; how its affixes and expansions tumble across the pages reveals the density of its grammatical structures and nuances in vocabulary. This dictionary is a technology of community storage, not unlike the mats that surround us on these walls, with their precise weaves and particular motifs. And, like mat-weaving, this dictionary-building was also largely the product of Sabahan women’s work.

Lasimbang walks us through the tedium of constructing something that will last: meticulous dot-matrix print-outs with dense annotations in the margins (“remove and refile wrongly placed entries”; “mark all glottal stops”; “back up working disks”) and painstakingly handwritten tables for the growing corpus of words and revised editorial timelines. Keeping a language alive means constant maintenance. And the dictionary continues to grow. Just as the weavers follow the pull of the weave, a language tugs at its speakers and writers. Both language and leaf are materials that choreograph their makers. The dictionary and the mat, both crucial to Yee’s show, are as much archives of the Sabahan people as they are part of an evolving repertoire of gesture and tongue.

In the final room, we finally get to spend time on a mat, rolled out for us like a red carpet before a projection at the far end of the room: Yee’s feminist choreography of indigenous masculinity. There, seven men, torsos bare, arms wrapped around each other, stare us down before they begin to move. They quiver and rotate on a single axis, connected by a seven-headed lalandau hat. The hat is traditionally worn on its own, its spires representing trees and embellished with feathers. But here, the bare spires are entangled in a thick canopy. We see the branches of social relations, unadorned by pomp and performativity. There’s no crown shyness: the dancers from Sabah’s Tagaps Dance Theatre are conjoined in both mind and body. A repeated disembodied yelp, which visitors hear the moment we step into the larger gallery space, originates from this room. It’s the shrill Murut warrior cry, pangkis, that gives this 9½-minute video its name. The pangkis can be used to summon a community, signal victory, or shield one from harm. But Yee has engineered the sound in reverse, so what we’re hearing is the howl of the warrior swallowed back into his body.

It’s hard to tear your gaze away from this dance sequence, combining classical and contemporary movements; the men vibrate together and veer away from each other, only to return. Some of them duck out of their headpieces, but they remain in touch with the rest of the group, quite literally—a palm on a thigh, an arm on a shoulder—until they rejoin their rhizomatic network. I read their performance as nonbiological brotherhood made sacred by ritual. The seven-headed hat has a long tail, suggesting that there’s room for more men to join the troupe. I sit on the mat for a long time, stroking the weave and watching the dancers flex and coil their bodies, their feet drumming rhythmically on the ground. The many will be here for the one.

I wander through “Mansau-Ansau” three times over the span of several weeks. I make different journeys across the gallery, lingering with each work a little longer. As I obey the gravitational pull of the show, it becomes a massive metaphorical mat on which new relationships are revealed to me and older ones are renewed. I’m drawn into the orbit of other wanderers; Yee’s work constellates us, makes us read and thread meaning into the spaces between us.

The first time, I’m alone, but I bump into one of my former students, whose own award-winning graduation showpiece, “Pancung Kepalanya! (Off with his head!)” (2023), featured a series of bullwhips she’d hand-braided with hair collected from female friends and classmates. She’s awed by the show, and we have a long conversation about her own artistic aspirations, and the kind of community-based and feminist work she wants to do.

The second time, Yee shepherds a small group of us through the show herself. She’s unabashed about caressing and handling her own works, and zigzags through the show with her own internal logic. She’s almost breathless with excitement, coming off the high of the dictionary workshop and the warmth of her elders, and it’s infectious. When I join my friends for dinner after, I’m giddy with Yee’s living work and life mission, but struggle to convey the enormity of it, my emotions sticky in my chest and on my tongue.

The third and last time, I invite two friends on a tour of the exhibition. This is the first time that I become both an emotional repertoire and a critical archive of Yee’s work, from storing and performing it in my own way. My companions ask me beautiful questions I can’t answer and point out exquisite details I’ve overlooked. Our whispered conversations circle around different paradigms of indigeneity, including from their home country of “so-called” Australia, which is grappling with its own histories of settler colonialism. We spend a long time on the mat in the last room, pouring out our hearts on a tikar that’s held so many others.

Yee may insist she’s a poor weaver of mats—she admits as much in a disarmingly candid Instagram post—but she’s certainly a powerful weaver of worlds. What she’s offered to those who wander through her body of work isn’t just an introduction to the generative circular economies of the tamu, the Bornean marketplace where society meets to exchange its goods and wares. Nor is it simply an indictment of colonialist expansionism. Our shared knowledge circulates through the desire paths we take and the relationships formed in our wake. Every time I exit the final room, I must trace my path back through the other two, back to the start. As I, like the kampung chicken, return home to roost, I’m reminded of our precolonial past, before the monocropping empires of industrial farming, or the cramped barns of genetically plumped-up chickens. I suppose its persistence (and even revival) speaks to the tenacity of these indigenous ways.

Mansau-ansau. We’ve wandered away from who we are, a journey choreographed by forces both familiar and imperceptible. How might we return to ourselves?

Corrie Tan is Jom’s arts editor. She is also the director of the Asian Dramaturgs’ Network. Corrie is indebted to Seet Yun Teng, Alya Rahmat, Leah Ginnivan and Wong Sue-Lin for their contributions to the final shape of this essay. Thank you for being part of this weave.

“Yee I-Lann: Mansau-Ansau” runs till March 23rd at the Singapore Art Museum at Tanjong Pagar Distripark.

Letters in response to this piece can be sent to arts@jom.media. All will be considered for publication on our “Letters to the editor” page.

If you enjoy Jom’s work, do get a paid subscription today to support independent journalism in Singapore.